Inclusion is the Answer

Abstract

Children with Down syndrome need to be included more often in social settings like the classroom despite their learning and physical disabilities. I will explain several strategies for inclusion.

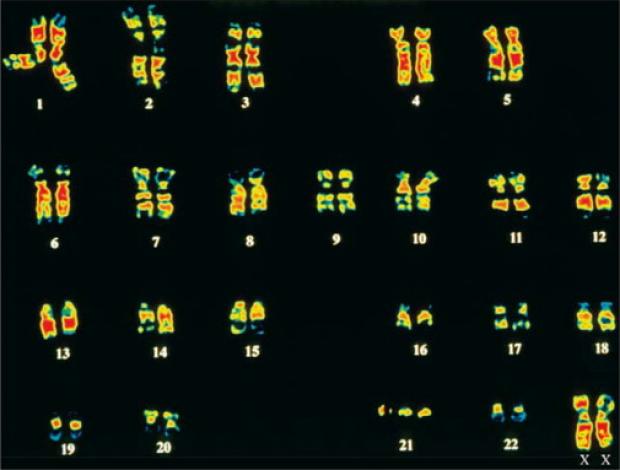

What does it look like to include a child who might appear, learn, speak, and act differently from the average student in an everyday classroom environment? A child with Down syndrome typically holds true to all of the differences listed above. Therefore, what does the image of an everyday classroom environment look and feel like when children with Down syndrome have the opportunity to be included? Medically, Down syndrome is defined as a genetic condition existing when there is an extra chromosome present in a child at birth. Chromosomes metaphorically serve as laundry baskets in our bodies, keeping all of the genes and cells in the body sorted and tidy. Due to the extra chromosome present in a child with Down syndrome, regular growth of the body in the fetus is disturbed, consequently disrupting the development of a child’s progress in their learning, cognitive skills, and motor functioning skills. All children with Down syndrome have some form of learning or intellectual disability, accompanied by a wide range of physical disabilities. As with any other child, the ultimate goal for parents and teachers alike is to improve and maximize any physical, mental, or social abilities for a child with Down syndrome. Incorporating them into an inclusive classroom setting in school is a logical answer for attaining this goal.

While inclusion has not always been an option in the educational field, it has become an important but easily overlooked opportunity for children with Down syndrome to take part in. In a classroom that implements policies of inclusion, the special education teacher works closely with the general education teacher to adhere to the needs of a variety of students with disabilities. The special education and the general education teachers, research and experiment with various teaching styles in order to find particular techniques that work best for a specific child with Down syndrome. As these children are able to be active participants in the learning process with their classmates, their own self-esteem and sense of ability to accomplish tasks presented to them are boosted. These children are able to gain social skills and an empowering sense of an “I can do this!” mindset from not being excluded or isolated in a strictly special education classroom. Typical children in the classroom are also benefiting by acquiring tolerance and acceptance of individuals who are different than they are. The ordinary, everyday classroom full of normal-functioning children experiences an overwhelming new vibe when children with and without Down syndrome are able to interact and build relationships with one another. When looking at the bigger picture, in addition to the typical child advancing from an inclusive classroom setting, a child with Down syndrome is able to acquire an improved self-esteem, a better sense of self, and improved developmental, cognitive, and motor functioning skills.

Before outlining the benefits and logical reasoning behind the implementation of inclusion for a child with Down syndrome more in depth, this essay discusses research relating to each of these factors. It will be important to understand the implications and characteristics associated with Down syndrome in order to gain insight into why inclusion needs to be an option for this child. In order to answer the question at hand, of whether inclusion should be an option for a child with Down syndrome in the primary school, this argument provides the necessary history and meanings of inclusion gathered from research. Also included, is the possible controversy against utilizing inclusion, before finally clearly defining the great benefits and reasoning for inclusion as a logical option for a child with Down syndrome.

Children with disabilities are faced with various obstacles, particularly in the educational field. As a child with Down syndrome in the primary school, being a part of a class is important. Actively taking part in an inclusive classroom setting allows for a child with Down syndrome to feel as though they are a part of the classroom with their nondisabled peers. While students are still faced with challenges, they are able to face these challenges with a better sense of self-confidence, as well as improved developmental and functioning skills. For example, in an inclusive setting, a child with Down syndrome will acquire a simple motor development skill by observing their nondisabled peers. Whether it is holding a pencil correctly to write or being able to hold blocks to build a tower, a child with Down syndrome gains these abilities through careful observation of peers and cooperation of teachers. Being a part of the inclusive classroom also allows the average student to acquire a sense of open-mindedness and respect for others.

Although, a commonly known disorder, the implications and characteristics associated with Down syndrome are often overlooked or not addressed early enough in a child’s developmental and social growth. In his book about Down syndrome, Mark Selikowitz covers the ins and outs of this disorder. Questions, especially for parents, are answered about the developmental growth of children with Down syndrome. Selikowitz clearly defines how Down syndrome comes about via an extra number 21 chromosome. He also breaks down the skills and/or lack of skills at each stage of life for an individual with Down syndrome. Connecting directly to Valentine Dmitriv’s book on the importance of early education for children with Down syndrome, these developmental delays and functioning skills are analyzed deeper. All children with Down syndrome have a form of an intellectual learning disability; and Dmitirv discusses the significance of intervening early in education for these children. Children are likely to take on a habit or improve their abilities the earlier the habits or skills are instilled in them. A child with Down syndrome is able to learn from their nondisabled peers at an early age in an inclusive classroom setting.

Implementing inclusion in a primary education classroom does not necessarily look the same in all classes. From the perspective of the classroom, in her collective book on cases of teaching styles in the inclusive setting, Boyle is conveying the teaching styles that work best and the styles that may not work. Strategies for Teaching Students with Disabilities in Inclusive Classrooms does not pertain directly to children with Down syndrome, but the strategies and concepts can be directly applied to including children with Down syndrome in an inclusive classroom setting. Many of the techniques discussed and demonstrated in the proceeding chapters–i.e.: group work, station teaching, collaborative teaching–include the necessary interaction of the nondisabled students and the child with Down syndrome as a key component. The article by the National Down Syndrome Society, titled “Implementing Inclusion”, supports the content of this book, stating that a study done reported “academic, behavioral and social benefits for students with and without disabilities” (Implementing Inclusion). The possible prejudice from parents that their typical student will be distracted and restricted in their learning abilities, as well as extra training and funding that may be necessary is made evident in this article, as an intended counterargument towards inclusion. The vast amount of learning that is done alongside the children with Down syndrome and the positive effects the new relationships built have on both children alike, however, far outweigh the subtle drawbacks and possible obstacles that are associated with inclusion for children with Down syndrome.

While Down syndrome is distinguishable and might be recognizable by the common person, the implications and causes are not widely known. As defined earlier, Down syndrome is a genetic disorder accompanied by an extra number 21 chromosome, indicating that a child born with Down syndrome has forty-seven chromosomes as apposed to the typical forty-six (Selikowitz 33). In his second edition of Down Syndrome: The Facts, Mark Selikowitz explains how the syndrome comes about, the various types, the characteristics and physical features, as well as the developmental and mental delays that are associated with Down syndrome. The extra chromosome present causes an abundance of specific proteins to form in the child’s cells, which in turn disrupts the normal development and growth of the child, contributing directly to the intellectual disability present in all children with Down syndrome. Trisomy 21 is the most common type of Down syndrome seen, characterized by a complete extra chromosome in every cell of the body (p. 34). It is important to understand, however, that not all children with Down syndrome have the same characteristics, but there are a few distinct features that are most common. Flattened facial features, a smaller head and shorter neck than normal, along with slightly upward-slanting eyes are some of the stronger appearances seen in children with Down syndrome. The tongues of these children are often larger and tend to stick out. One of the main characteristics is seen in the broadness, often stubbiness, of the child’s hands and feet. This is joined by low muscle tone, or a weaker ability to resist throughout the muscles (MayoClinic). These discrete qualities that can be affiliated with Down syndrome directly contribute to some of the disabilities of the syndrome. Because of the previously discussed intellectual disability existent in Down syndrome, development is naturally going to be a slower process. The affected areas of development include a child’s gross-motor, fine-motor, personal and social, language and speech, and cognitive development (Selikowitz 60-61). Each of these developments, as well as their ability to improve, will be discussed in greater detail during the main argument. These developments involve simple, daily tasks that may be more difficult for a child with Down syndrome than for the average child. Well-stated by Selikowitz, however, is the argument that “with appropriate education, children with Down syndrome can certainly develop more rapidly than was formerly thought.”

This appropriate form of education for a child with Down syndrome is known as inclusion. Pertaining to the field of education, inclusion is defined as “the education of students with disabilities within the general education setting and under the direction of both the general education teacher and special education teacher” (Boyle 33). Evident by the components of this definition, inclusion involves collaboration from multiple individuals in order to best incorporate the child with Down syndrome. The implementation of inclusion in the education setting became easier and better understood with the passing of the Individuals with Disabilities Education Act (IDEA) of 2004. With influential goals and designed to address past discriminations of children with disabilities, IDEA had a primary aim to: “ensure that all children with disabilities have available to them a free appropriate public education that emphasizes special education and related services designed to meet their unique needs and prepare them for further education, employment, and independent living” (Boyle 8).

Inclusion, which evolved and changed from the previous term of “mainstreaming”, is a direct component of this act because the special education services are offered to the child with Down syndrome while in the general education setting. Providing inclusion for children with Down syndrome early, in the primary school for instance, allows them to develop habits and abilities at a time when their development is most susceptible to learning. Believe it or not, a child with Down syndrome has the capacity to learn skills rather rapidly, in respect to both cognitive activities and fine motor skills (Dmitriev 26). It is vital for a child’s ultimate improvement to get started early with inclusion in order to take advantage of their prompt learning skills. Incorporating inclusion for a child with any type of disability focuses on teaching the child in an environment with typical children and making the child an active participant in classroom activities (Boyle 34). These goals and aims of inclusion provide direct benefits to a child with Down syndrome in all aspects of learning and developmental growth.

Allowing a child with Down syndrome to participate in inclusion enables the child to improve skills in the classroom as well as in their everyday lives outside of the classroom. It is known that children with Down syndrome are developmentally delayed in many areas, including their motor functioning skills and cognitive skills, as well as their normal mental and emotional development (Dmitriev 35). Through participation in inclusion, these children are able to improve these skills and to master goals that are set by teachers and parents. Fine motor skills, for example, are easily strengthened, by being in an inclusive setting with nondisabled children everyday. Simple tasks such as picking up an object, properly using scissors, building with blocks, or holding a pencil correctly to draw a picture all require the use of fine motor skills by any human being (Selikowitz 44). A child with Down syndrome has the benefit of working on these specific skills, as well as watching their average peers in an inclusive setting perform these tasks, in order to improve their ability to accomplish the same task. While these are all very important to the overall benefits associated with inclusion, the most important one comes in the child’s improved social development and betterment. Children with Down syndrome gradually weaken in their social development (Dmitriev 40). Inclusion offers a variety of social interactions and opportunities for a child with Down syndrome. Being able to participate and engage in activities with their nondisabled classmates gives the child an enormous amount of confidence. A positive sense of encouragement is given from the typical child to the child with Down syndrome (Implementing Inclusion). The child gets the idea that they are able to accomplish what their classmates are doing; and the typical student is able to support this idea, giving the child with Down syndrome the motivation to do so, as well as an overall empowering sense of self. In addition to the child with Down syndrome, reports have shown that the nondisabled student benefits socially, academically, and behaviorally from being in an inclusive classroom setting (Implementing Inclusion). The exposure and acceptance of diversity that the typical child receives from inclusion is phenomenal. He or she is learning to not only be tolerant of an individual who is different than they are at a young age, but he or she is also able to build relationships with students that they otherwise may not come into contact with on a daily basis. In an inclusive setting, the typical child learns from and is inspired by a child with Down syndrome’s ability to accomplish tasks and overcome obstacles despite the challenges that they may encounter (“Inclusive Education”). As a whole, both the child with Down syndrome and the typical student draw crucial social benefits from active participation in an inclusive classroom setting.

In order to maximize these benefits for both types of students in an inclusive setting, effective teaching styles and strategies are necessary. Collaboration is a key element in successfully practicing inclusion. In the case of an inclusive classroom setting, “collaboration involves two people working together to achieve a shared goal” (Boyle 34). The general education teacher works in collaboration with a special education teacher with the common goal of teaching and benefiting both children with and without Down syndrome. According to a study done by the National Center on Educational Restructuring and Inclusion, the collaborative teaching model reported various positive social and behavioral outcomes for both types of students, as well as no negative effects on academia for the students (Boyle 34). Similar to the relationships built in the classroom among the Down syndrome students and the typical students, collaborative teaching is a learning process for the teachers, based upon respect, confidence, and encouragement for one another. This “style of interaction” among teachers involves a shared participation from both individuals, similar to the engaging participation among nondisabled children and children with Down syndrome (Boyle 35). Teachers and students alike are able to learn from each other in an inclusive classroom. It has been found that teaching styles including minimal withdrawal and allowing for normal involvement in the curriculum work best for children with Down syndrome. It is important to enforce the working together and collaboration of a child with Down syndrome and their nondisabled peers, but to simultaneously be able to encourage the child to be an independent learner (Lorenz). Various teaching styles can be utilized and experimented with during inclusion. Teachers are likely to succeed and help their students reach their goals more efficiently by trying different styles and choosing the ones that seem to work best for a class as a whole, or possibly by combining various styles in order to accommodate for more students. Various styles include: station teaching, alternative teaching, interactive teaching, and parallel teaching. Interactive teaching involves the collaboration of one teacher leading in front of a class while the other teacher serves more as support and monitors students’ learning and progress of a particular concept or task (Boyle 42). Michele Mazey, an adaptive Physical Education teacher in the Pitt County school system in Eastern North Carolina, supports the researched benefits associated with inclusion for children with Down syndrome. As an adaptive P.E. teacher, Ms. Mazey is able to travel to various schools in Pitt County and participate and teach physical education in both inclusive and non-inclusive settings. An advocate for inclusion, Mazey states, “students with Down syndrome excel working in inclusion.” Inclusion tactics work so well for these children because they are able to model perfectly. In the physical education atmosphere for example, a student with Down syndrome watches his or her peers closely and is able to imitate their actions to the best of their ability, which is often almost perfect (Mazey). Children with Down syndrome are extremely smart; with one of their other main characteristics being stubbornness, they will often get frustrated and think they are unable to complete an exercise, or an assignment. From firsthand experience in inclusive settings, Mazey says that the nondisabled students love being involved with the children with Down syndrome. “They (typical children) see the disability and are often more open to these students, aiding in their learning process.” (Mazey). Variations of inclusion are seen, specifically in the physical education field, in student-teacher interactions as well as student-student interactions, in order to maximize relationships and building of confidence and trust. As with any other classroom, it is important that teachers and students work together in an inclusive classroom setting in order to reap the associated social, behavioral, and academic benefits, especially for the child with Down syndrome and for the nondisabled student.

In potential opposition to this policy, the question arises of whether there is sufficient funding available in education, or the proper resources and knowledge of teachers available, for the implementation of inclusion. A common question and argument in any situation involving education, the issue of funding is not pertinent to inclusion. According to a research synthesis conducted on teachers’ perceptions of inclusion, the majority of the 10,560 teachers surveyed agreed upon the overall concept of inclusion for children with disabilities (Scruggs). Teachers’ agreeing on this matter suggests that any extra funding and/or training that might be necessary can and should be done in order to make inclusion an option for all children with Down syndrome. In addition to collaboration, teachers will utilize the resources already available as well as continue to educate themselves for the overarching purpose of achieving a child’s goals. From personal experience, being placed in an inclusive daycare setting at a young age, I have experienced firsthand the benefits associated for the typical student. The value of the special friendships that are built between a child with Down syndrome and a nondisabled student cannot be put into words. A price cannot be placed on the ability of a teacher to improve a child’s social interactions with their peers, the opportunity for children with and without disabilities to build friendships, or the optimistic outlook that a child with Down syndrome attains. The argument and questionable issue of funding does not compare to these attributes. A child with Down syndrome in inclusion experiences an overwhelming sense of self-confidence, improved life skills and the ability to participate in activities with their classmate.

Sources

Boyle, Joseph. Mary Provott. Strategies for Teaching Students with Disabilities in Inclusive Classrooms. United States: Pearson Education Inc, 2012. Print.

Dmitrev, Valentine. Early Education for Children with Down Syndrome: time to begin. Austin, Texas: Pro-Ed, 2001. Print.

“Implementing Inclusion.” – National Down Syndrome Society. National Down Syndrome Society, 2012. Web. 3 Mar. 2013.

“Inclusive Education | Benefits of Inclusion | Down Syndrome South Africa.” Down Syndrome International, n.d. Web. 3 Mar. 2013.

Lorenz S. Making inclusion work for children with Down syndrome. Down Syndrome News and Update. 1999;1(4);175-180. Web. 1 March 2013.

Mazey, Michele. Telephone Interview. 20 April 2013.

Scruggs, Thomas E., and Margo A. Mastropieri. “Teacher Perceptions of Mainstreaming/inclusion,1958-1995: A Research Synthesis.” Exceptional Children 63.1 (1996): Council for Exceptional Children, 22 Sept. 1996. Web. 1 Mar. 2013.

Selikowitz, Mark. Down Syndrome: the facts. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. Print.

Staff, Mayo Clinic. “Definition.” Mayo Clinic. Mayo Foundation for Medical Education and Research, 07 Apr. 2011. Web. 1 Mar. 2013.