Moral Philosophy and the Dialogic Tradition: Izaak Walton’s The Complete Angler

Abstract

There is no doubt that the defining religious, political, and economic framework of seventeenth-century England had its influences on the Angler. Walton’s character Piscator alludes to this social framework directly when he scornfully mentions the “Critical age.” Moreover, given the frequent appearance in the Angler of various allusions and commentaries regarding popular topics of the day (some more explicit than others), many scholars have analyzed Walton’s work as a critical response to the dissolution of the Charles monarchy and the subsequent ideological crisis of 1649-1689. This angle of approach is credible. Jonquil Bevan calls this historical basis “the fundamentally serious purpose [of the Angler].” Yet this approach does not agree with the lucid, jovial language Walton employs in his discourse. For example, Walton never directly comments on Anglicanism or Puritanism, nor do his characters once utter the words “Charles,” “Cromwell,” or “England.” This lack does not suggest Walton himself was ignorant of figurative language or symbolism; rather, his decision to write discreetly seems to position the Angler as a philosophical text rather than a concentrated, historical one.

1

In 1642, English theologian Thomas Goodwin offered the following consolation to a fast-day congregation:

[Our] Nation is in a wofull plight…But on the contrary, if we turn from our evil ways, God will perfect his building, and finish his plantation, he will make us a glorious Paradise, an habitation fit for himself to dwell in.2

Ten years later, in his book The Compleat Angler, Izaak Walton would anticipate this same utopian ideal, which he labels the “observation of the nature and breeding, and seasons, and catching of fish,”3 or simply, the “Art of Angling.”4 One of the most accredited bibliographical studies of Walton’s discourse on fishing lists some “two hundred and eighty-four editions, facsimiles, and reprints” of the text, indeed making the Angler one of the “most popular works in the [English] language.”5 While much can be said on the question of why so many revisions exist, and the extent to which these revisions were influenced both by Walton and by external scholarship, this essay will focus solely on the author’s original, 1653 edition.

There is no doubt that the defining religious, political, and economic framework of seventeenth-century England had its influences on the Angler. Walton’s character Piscator alludes directly to the significance of these social circumstances when he scornfully mentions the “Critical age.” 6 Moreover, given the frequent appearance in the Angler of various references to and commentaries on popular topics of the day (some more explicit than others), many scholars have analyzed Walton’s work as a critical response to the dissolution of the Charles monarchy and the subsequent ideological crisis of 1649-1689. This angle of approach is credible. Jonquil Bevan calls this historical basis “the fundamentally serious purpose [of the Angler].”7 Yet the approach does not agree with the lucid, jovial language Walton employs in his discourse. Furthermore, Walton never directly comments on Anglicanism or Puritanism, nor do his characters once utter the words “Charles,” “Cromwell,” or “England.” This formal decision does not suggest that Walton himself was ignorant of figurative language or symbolism (one could easily interpret Piscator, for example, as a common, English “all-man”); rather, his decision to write discreetly seems to position the Angler as a philosophical text rather than a concentrated, historical one.

This paper will first consider both of these angles (the discourse as a reaction to political and social pressures in England, and then as a universal, metaphysical text to inspire a bitter nation) insofar as they answer the question of why Walton chose to write this book. By situating the ideological disaster of civil war as a contextual backdrop, Walton’s initial motives behind the Angler become clearer. Nevertheless, examining Walton’s literary form as a method of thematic emphasis justifies only one of these methods of analysis. Ultimately, through Walton’s use of Biblically inspired pastoral language and the traditionally structured dialogue, the Angler serves as a morally didactic, philosophical text with lessons extending far beyond the scope of the concentrated events in seventeenth-century England.

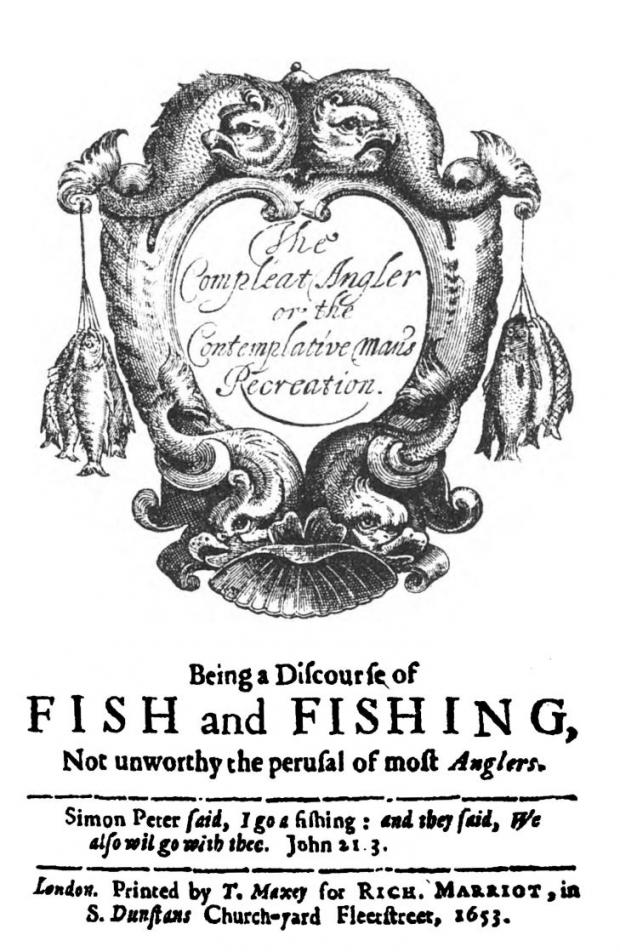

Despite its deceptively naturalistic title (in full: The Compleat Angler or the Contemplative Man’s Recreation. Being a Discourse of Fish and Fishing, Not unworthy the perusal of most Anglers) and a majority of its text being devoted to the technical details of angling, the Angler has largely been ignored as a precursory fishing manual. The reason is twofold; first, much of Walton’s technical content—“that is, the parts on how to catch fish and directions to tie flies”—is largely “cribbed from other books.”8 Secondly, one cannot ignore the historical context surrounding this work without suggesting that Walton’s inspiration was independent of the fundamental political, religious, and economic developments in England during his time. As John Turrell points out in his essay on fishing literature, most angling books until the end of the sixteenth-century “appear to have dealt with the art of angling only incidentally.”9 Such is the case with the Angler. Walton published his fishing treatise less than one month after Oliver Cromwell dissolved the established Rump Parliament, a move that forced “a considerable body of men…out of public service and into private life.”10 Anglicans and Royalists, two groups with which Walton would have undoubtedly associated himself, were also displaced and forfeited under the unconstitutional rule of the Lord Protector. Migrations to the countryside were becoming increasingly popular, particularly as Parliament began levying taxes against the citizens of London. Records of farmland investments near the rural town of Stafford point out that Izaak Walton was among these migrants11. It comes as little surprise, then, that B. D. Greenslade would posit the importance of the “sequestered clergy”12 Walton’s impulse in drafting The Compleat Angler.

If angling was thus identified with the life of the Anglican clergy, it might be expected that a book on angling published in 1653, when the Church was dispossessed and the Royalist clergy scattered, would be more than a work of practical instruction in how to fish…13

Indeed, the Angler served as a relatively foolproof way for Walton to safely voice his opinions against Cromwell while simultaneously praising the “virtues that flourished in [the] adversity” of his fellow countrymen14. In addition, Greenslade suggests that the technical knowledge in the Angler “would have been…welcomed from men who had been forcibly relieved of their duties, and had leisure to practice the art.”15 Walton’s ecclesiasticism cannot be ignored. The relationship between his firm Royalist attitude and the newly dissolved Anglican clergy made a strong point for the Angler. Nevertheless, the actual text of Walton’s book does not support this specified, historical theory; the words “Anglican,” “clergy,” “execution,” and “England” are all missing. Lessons propounded by the wise Piscator have nothing to do with divine monarchical election or the merits of the Book of Common Prayer. Instead, Walton anticipates a philosophical reading of his discourse by way of form and style; he employs anecdotes, fables, songs, and other philosophical ornaments to present a universal perspective, applying not only to the historical evolution of England, but also to the general moral state of humanity. Kenneth Rexroth phrases it beautifully when he writes of the Angler, “[w]e read Izaak Walton for a special quality of the soul.”16

Walton understands not only the difficulty of undertaking a morally corrective piece of literature, one that he must propagate to a general audience, but also the inevitable futility of it. He expresses this vulnerability in a prologue to his friend John Offley when he labels himself the “unlearned Angler,”17 and suggests that John “[knows] that Art better then any that I know.”18 English critic H.J. Oliver adds that “when Walton set out to compose The Compleat Angler he had some idea of what was expected…and some idea of the pitfalls.”19 It is not certain whether the skepticism in his prologue reflects a deeply troubled Walton or a playful jest with a close companion; most likely, it is a combination of both. Walton’s decision to persevere in his attempt is not necessarily a reflection of his overcoming the obstacle of hardship, however, as many of his contemporary English writers seemed fond of the enlightenment and spiritual exercise inherent in the trials of everyday life (John Milton, for example, writes in Areopagitica: “I cannot praise a…virtue, unexercised and unbreathed”20). Rather, Walton was motivated by the beauty of companionship; the very framework of the Angler thus becomes an intimate journey, one which Walton specifically addresses as Piscator declares: “Good company makes the way seem the shorter,”21 and, “’Tis the company and not the charge that makes the feast.”22 Walton’s mission mirrors that of the zealous courtier, rendering the book of the Angler a symbol of the idyllic garden bench upon which Thomas More engages with Raphael in the garden. I will now support our second angle of approach by illustrating that the foundation for Walton’s argument lies in his depiction of the relationship between the natural world and the spiritual as well as in the formal implications of the dialogic tradition that unfolds between Piscator and Viator.

Walton was deeply troubled by the religious ramifications of the seventeenth-century. In a crucial document entitled “Walton on His Own Times,” Walton decries England’s infestation of “godless men,”23 men that “had so long given way to their lusts and delusions, and so highly opposed the blessed motions of His Spirit.”24 Walton speaks through Piscator when he comments on the fraudulent pride of

“mony-getting-men,” those that “spend all their time first in getting, and next in anxious care to keep it; men that are condemn’d to be rich, and always discontented…poor-rich-men”25

Anglers on the other hand, according to Piscator, “enjoy a contentedness above the reach of such dispositions,”26 a spiritual satisfaction available to all “children of Israel…[who sit] by the Rivers of Babylon…bemoaning the ruines of Sion.”27 These ruins are the decrepit buildings and abandoned pastures of Charles Goodwin’s 1642 sermon; they are an image of England “wretched” and “reprobated”28 under the tyranny of Oliver Cromwell and the Puritans who had overthrown the episcopacy. The Angler then becomes a kind of cloister, a spiritual oasis among the desert sands of arid human nature. Walton bolsters this argument when he observes that, of the twelve “prudent and pious…Apostles of our Savior,” “only three [were chosen] to bear Him company, [and] these three were all Fisher-man.”29 Piscator then quotes “The Anglers Song,” singing: “I therefore strive to follow those, / Whom he to follow him hath chose.” 30

John Cooper upholds this pervading religious sentiment when he writes that, “More important to The Compleat Angler is a view of nature as providing the immediate experience of God’s bounty and goodness.”31 Crucially, Walton does not limit this bounty to specific individuals or groups; any person is free to find solace in the Angler, as its structure and theme are unbiased and universally inspiring. Still, while it is hard to discriminate between Walton’s social criticisms and the possibility of his discourse as an exclusive text, it seems safe to assume that Walton’s gibes do not necessarily limit the beneficiaries of his philosophy. Above all, Walton seeks to offer comfort to his readers, as Bevan puts it: “to cheer his readers up.”32 In the spirit of the Angler’s didactic style, Walton does not simply offer an epic catalogue of righteous action every person should adopt. Rather, his ethereal descriptions of nature and the pastoral images hearkening to the most basic relationship with mother-earth become the means of contemplation necessary for spiritual enlightenment. For Walton, this sense of understanding cannot simply be encouraged, it must be experienced. “Walton is anxious to draw his readers as directly as possible into his fiction,”33 “he wants us to see the fish he is describing,”34 (hand-printed engravings are common in most editions) and join in on the jovial alehouse songs (sheet music even appears in the 1676 edition); however, Walton understands that his audience might not learn anything from his discourse, that it will likely “contribute nothing to…knowledge”. 35 Walton’s words, images, and songs encourage readers of the Angler to look past the scientific language of instruction, to lay down the sword and the Bible, and position them to, instead, consider the lessons propounded by the natural world around them.

The Angler purposefully begins on a “pleasant fresh May day in the Morning,”36 alluding to the date of May 1—the commencement of summer—and more discreetly to the ancient worship of Flora, the Roman Goddess of flowers. To present nature with “innocent Mirth,”37 Walton does not intend “to please [his] self.”38 He also does not care to accommodate those “sever, sowr complexioned men,”39 including not only the “sectaries and Puritans to whom [he] and his friends were opposed,”40 but also the population of men privy to “Scriptural…and lasvicious jests,”41 men with “folly ripe…in reason rotten.”42 Such is the Piscator’s opinion of the huntsmen he and Viator encounter early in Chapter II: they offer no “wit and mirth,”43 of which the angler is particularly fond; rather, they offer only their sin and corruption. Walton is simply offering criticism here; this criticism, however, does not rebuke these individuals from the moral benefits expounded in the Angler. Piscator explains the virtues of the fisherman—“being leaned and humble, valiant and inoffensive, virtuous and communicable”44—and in so doing illustrates Walton’s concern “to define recreation in his own sense and, by repudiating improper forms of it, to defend it.”45 Walton sets out his plans to make “a recreation, of a recreation,”46 to illustrate through pastoral images, quaint hospitality, rural ditties, and countless anecdotes and proverbs the spiritual virtues of nature and of human interaction with nature. Thus, in his own interpretation of J. Denny’s 1613 poem, “The Secrets of Angling,” Walton writes:

All these, and many more of his Creation,

That made the Heavens, the Angler oft doth see,

Taking therein no little delectation,

To think how strange, how wonderful they be;

Framing thereof an inward contemplation,

To set his heart from other fancies free;

And whilst he looks on these with joyful eye,

His mind is rapt above the Starry Skie.47

That Walton borrowed and often revised much of the content used and copied in the Angler reflects a sense of urgency to communicate his larger purpose. The poems and songs reiterated by Piscator and Viator become a direct means for Walton to speak to his audience as these inserts are often directed ambiguously and seem less connected with the dialogue. For example, a speaker will often introduce the original author before reciting the work. In addition, Walton uses indentation and italics to set his sources apart from the surrounding text. While the core of the dialogue and its execution are crucial to the success of the Angler, the majority of Walton’s philosophical voice is translated through his poems, anecdotes, and songs. Bevan describes this propensity as Walton “[abandoning] his usual prose register for a consciously literary level of style.”48 Often, Walton will offer these interjections as pithy summaries or reflections on the thoughts or observations preceding them; for example, after Piscator observes the “Silver streams” and their tendency to “glide silently towards their center, the tempestuous Sea, yet sometimes opposed by rugged roots, and pibble stones, which broke their waves, and turned them into fome,” he offers the following analysis:

I was for that time lifted above the earth;

And possest joyes not promis’d in my birth.49

Again, Walton impresses upon his audience the metaphysical power of nature to lift one’s soul to a heightened state of consciousness, to purify thoughts and fancies so that humans may be closer to the divine. The raw, carnal state of humanity contrasts sharply with the ethereal essence of enlightened thinking. The same relationship reveals itself in Walton’s use of the microcosm, when Piscator quotes “The Anglers Song,” singing:

Fresh rivers best my mind do please,

Whose sweet calm course I contemplate,

And seek in life to imitate;50

“The Anglers Song” suggests a comparison between how nature and humans operate—that mysterious connection in which qualities of one are organically imitated in the other. Two hundred years later, Henry David Thoreau would observe the “innumerable little streams”51 of Walden Pond that “overlap and interlace with one another, exhibiting a sort of hybrid product”52. Thoreau points out that the streams, cutting through the “sandy overflow”53 of the water’s banks, make him feel “nearer to the vitals of the globe,”54 for the image seems “a foliaceous mass as the vitals of the human body.”55 Although less scientific in observation, Walton would have agreed that nature constitutes the lifeblood of mankind, delivering nourishment above all to the deprived human spirit.

Toward the end of chapter IV, the tone of Walton’s borrowed texts—or the tone that Walton fashions to those texts—turns from ethereal and contemplative to something more concrete and practical. This transition is particularly evident as the bulk of Piscator’s technical fishing instruction occurs immediately after, in chapters V-XII. In the following anecdotes, poems, and songs, Walton explains the role of virtuous men in society. Later in chapter XIII, Walton’s quotes take on a much more decisive and active tone, a change that brings an even greater sense of urgency to the work.

After a strong rain shower Piscator and Viator pause in their discussion on fly-fishing and observe “how pleasantly [the] Meadow looks,”56 and how it “smels as sweetly too.”57 Piscator recalls what “holy Mr. Herbert” might say of such afternoons, and he quotes:

Sweet day, so cool, so calm, so bright,

The bridal of the earth and skie,

Sweet dews shal weep thy fall to night,

for thou must die…

…Only a sweet and vertuous soul,

Like seasoned timber never gives,

But when the whole earth turns to cole,

then chiefly lives.58

Walton’s image of the tree symbolizes Piscator and the fraternity of virtuous fishermen living amongst the filth of society. Not only can they withstand whatever great incendiary force has reduced humanity to a blackened, chalky mass, but they can feed off this divine apocalyptic retribution as if the dust from the coal were some kind of nourishing spiritual supplement. Walton uses a poem by Frank Davison to expound on this idea of a corrupt society and how anglers position themselves in such an environment. He posits first: “no life so happy and so pleasant as the Anglers, unless it be the Beggers life in Summer,”59 then he quotes:

What mirth doth want when beggars meet?

A beggers life is for a King…

…The world is ours and ours alike,

For we alone have world at will;

We purchase not, all is our own…

Thus beggers Lord it as they please,

And only beggers live at ease60

Walton has again drawn the comparison between what he calls “The City full of wantonness,”61 and the “sweet contentment the country man doth find.”62 For the countryman, or any persosn with virtue and patience, “His pride is in his Tillage,”63 and “No Emperor so merrily does pass his time away.”64 From the countless examples throughout the Angler that point to this same reasoning, it is evident that Walton has a clear definition of what separates the person who angles from the person who understands the art of angling. As Piscator concisely reminds Viator, the virtue lies simply in the ability to “be free and pleasant and civilly merry.”65 Walton’s decision to employ flowing, pastoral images and singsong poems and anecdotes accomplishes that very purpose Bevan alludes to: namely, to provide a comfortable exercise of the spirit, to cheer the audience up. There is nothing complex about this theme; to inject hidden and ambiguous meaning would be to contradict the simplicity of the angler himself, and to exclude those simple men from the text’s knowledge. My final argument will suggest the importance of Walton’s formal use of dialogue as an instrument to support this conclusion.

Walton did not intend to write a scholarly thesis with scientific images, complex case studies, and a strict academic language; he himself said, “God leads us not to heaven by hard questions.”66 Further, as Walton suggests, “he that shall read the humble, lowly, plaine stile of that Prophet [Amos], and compare it with the high, glorious, eloquent stile of the prophet Isaiah (though they both be equally true) may easily believe [Amos] to be a good natured, plaine Fisher-man.”67 H.J. Oliver reminds us that contemporary sixteenth and seventeenth-century dialogues such as Roger Ascham’s Toxophilus—in which a pupil learns archery from his master—and Castiglione’s Courtier, were undoubtedly influential technical writings for Walton. Oliver concludes that “the use of the dialogue by Walton’s predecessors is so common, one might well wonder whether he ever thought for a moment of writing his books in any other way.”68 Undeniably a cynic by the tone of his essay, Oliver does not praise the use of dialogue in the Angler; rather, he dismisses it as a convention used too lightly and too traditionally. The dialogue is a convention nonetheless, and it must therefore be lauded for its simplicity and humbleness. What Robert Boyle calls the “conferences” between his characters in Occasional Reflections Upon Several Subjects with a Discourse About Such Kind of Thoughts are a

way of writing [that] allows [for] a Scope of Diversity of Opinion, for Debates, and for Replies, which most commonly would be Improper, where only a single speaker is introduc’d: Not to add, that possibly if this way of writing shall be Lik’d and Practic’d, by some Fam’d and Happier Pen, that were able to Credit and improve it; it may afford Useful Patterns of an Instructive and not unpleasant Conversation.69

The Angler separates itself, however, from the multitude of dialogue literature available during Walton’s time because, as I have argued, its purpose extends far beyond the technical knowledge of angling Walton largely borrowed from contemporary lackluster fishing manuals. Rather, the Angler is an exposition of the beauty of art and moral wisdom in that recreation; its descriptions of nature and the lucid technical form of Piscator’s and Viator’s relationship position the book as a means to meditative transcendence and virtuous understanding. As Cooper reminds us, however, Walton’s discourse is a “philosophical dialogue”70, and thus, it presents its readers with a form of “dramatic conflict.”71 This conflict unfolds in the learning of young Viator. Impressed by Viator’s acuity, Piscator assures the novice that “you wil make an Angler in a short time.”72 Earlier, he also says, “and I doubt not but that if you and I were to converse together but til night, I should leave you possess’d with the same happie thoughts that now possesse me.”73 Yet, there is a problem; keeping with the dialogic tradition of converting the scholar or dissenter before the practical and moral instruction, Viator fails to accept or appreciate exactly what Piscator is attempting to instill. This failure explains Viator’s enthusiasm throughout most of the book concerning the technical and empirical lessons of his master, rather than his learned, moral lessons–the profound lessons expounded in the poems and anecdotes. This conflict accounts for Piscator’s bout of frustration in chapter IX when Viator pleads “Nay, good Master, one fish more…,”74 to which Piscator exhaustingly replies: “But Scholer, have you nothing to mix with this Discourse, which now grows both tedious and tiresome? shall I have nothing from you that seems to have both a good memorie, and a chearful Spirit?”75 Viator is disillusioned and does not initially understand the moral essence of his instructor’s motives; thus, when unable to catch a fish, he offers ignorantly, “I have no fortune.”76 For the critical reader, the problem is obvious; Piscator tells Viator in chapter IV, “I will give you more directions concerning fishing; for I would fain make you an artist.”77 He does not say: “…for I would fain make you a fisherman,” a substitution that would change the entire meaning of Piscator’s role in Walton’s dialogue; he is foremost an instructor of the arts, not the sciences. Had this word been changed, Viator’s frustrations regarding luck might be justified. Ultimately, through the trials of experience, Viator gains his insight: “Wel Master…I thank you for your many instructions, which I will not forget; your company and discourse have been so pleasant, that I may truly say, I have only lived, since I enjoyed you.”78 Piscator reminds us in chapter I that contemplation and action are requisite for the art of angling; if Walton’s use of poetry, mirth, and song constitutes the contemplative nature of the Angler, then the dialogue between Piscator and Viator constitutes the active. The dialogue, thus, is a crucial part of the whole—not only does it serve as a gentle bridge between Walton and his audience, but it brings credibility to what would otherwise be an argument propounded by its own creator. As a formal technique, the dialogue is lucid and effective; Kenneth Rexroth writes of it: “Nothing is obscure or troubled. Once we have accepted the archaic diction, nothing stands between us and the subject—except the personality of Izaak Walton, and that is as transparent as crystal, with an innate clarity achieved without effort,” achieved with “innocence.”79

In a close reading, The Compleat Angler loses all credibility as a fishing manual. Walton suggests a similar understanding during Viator’s first experience handling the fishing rod; he cannot match his master’s skill despite using Piscator’s own rod and tackle. Piscator explains, “that every one cannot make musick with my words which are fited for my own mouth.”80 Thus, the Angler becomes a medium for individual expression and experimentation; the uninterprative techniques of angling are far less important than—if not obsolete compared to—unique definitions and interpretations of spirituality and enlightened thought afforded by nature’s beauty. These are the sentiments that take hold of the readers’ soul; in Walton’s world there “dwell no hateful looks, no Pallace cares, / No broken vows…nor pale fac’d fears.”81 The fine balance between action and contemplation lauded by Walton emerges through Piscator and Viator as they fish and discuss under the ubiquitous shelter-tree. Indeed, the Angler itself becomes a form of protection for Walton’s readers seeking respite from the horrors of modern society, a pastoral oasis reminiscent of Virgil’s first Eclogue when Meliboeus says, “Tityre, tu patulae recubans sub tegmine fagi silvestrem tenui musam meditaris avena.” (Tityrus, resting under the shelter of a broad beech tree, you contemplate the woodland muse with your slender pipe.)82 The Angler is an inspiring “farewell to the vanities of the world,”83 it will forever echo the emotional verse of Henry Wotton: “Fly from our Country pastimes, fly / Sad troops of human misery,”84 as it passes genially the oaten flute to those common dissenters of contention, and “[lovers of] quietness, and vertue, and Angling.”85

1 Original 1653 ed. etching, William Strang and D.Y. Cameron

2 Rosman, 88

3 Walton, 59

4 Walton, 61

5 Cooper, 2

6 Walton, 89

7 Bevan, 36 [my emphasis]

8 Prosek, 14

9 Turrell, xi [my emphasis]

10 Bevan, 2

11 Bevan, 17

12 Cooper, 27

13 Cooper, 27

14 Cooper, 27

15 Cooper, 27

16 Rexroth, 142

17 Walton, 57

18 Walton, 57

19 Oliver, 297

20 Milton, 33

21 Walton, 63

22 Walton, 96

23 Le Gallienne, 413

24 Le Gallienne, 413

25 Walton, 64

26 Walton, 70

27 Walton, 70

28 Le Gallienne, 413

29 Walton, 74

30 Walton, 97

31 Cooper, 50

32 Bevan, 36

33 Bevan, 44

34 Bevan, 44

35 Walton, 58

36 Walton, 63

37 Walton, 155

38 Walton, 59

39 Walton, 88

40 Bevan, 52

41 Walton, 82

42 Walton, 91

43 Walton, 88

44 Walton, 68

45 Bevan, 38

46 Walton, 59

47 Walton, 78

48 Bevan, 50

49 Walton, 89

50 Walton, 96

51 Thoreau, 2031

52 Thoreau, 2031

53 Thoreau, 2031

54 Thoreau, 2031

55 Thoreau, 2031

56 Walton, 111

57 Walton, 111

58 Walton, 111-112

59 Walton, 112

60 Walton, 113

61 Walton, 94

62 Walton, 94

63 Walton, 95

64 Walton, 95

65 Walton, 68

66 Walton, 75

67 Walton, 75

68 Oliver, 299

69 Boyle, xiv

70 Cooper, 87

71 Cooper, 87

72 Walton, 85

73 Walton, 67

74 Walton, 137

75 Walton, 137

76 Walton, 107

77 Walton, 114

78 Walton, 163

79 Rexroth, 144

80 Walton, 107

81 Walton, 163

82 Bevan, 51

83 Walton, 161

84 Walton, 160

85 Walton, 163

Sources

Bevan, Jonquil. Izaak Walton’s the Compleat Angler. Sussex: The Harvester Press, Ltd., 1988. Print.

Boyle, Robert. Izaak Walton and the Art of Angling. Routledge: Prose Studies, 2008. Print.

Cooper, John R. The Art of the Compleat Angler. Durham, NC: Duke UP, 1968. Print.

Greenslade, B.D. “The Compleat Angler and the Sequestered Clergy.” Review of English Studies 5.20 (1954): 361-366. Print.

Oliver, H.J. “The Composition and Revisions of “The Compleat Angler”.” Modern Language Review 42.3 (1947): 295-313. Print.

Prosek, James. The Complete Angler. New York: Harper Collins, 1999. Print.

Rexroth, Kenneth. Classics Revisited. New York: Avon Books, 1968. Print.

Rosman, Doreen. The Evolution of the English Churches: 1500-2000. Cambridge: Cambridge UP, 2003. Print.

Thoreau, Henry D. “Walden, or Life in the Woods.” The Norton Anthology of American Literature. Ed. Nina Baym. New York: W.W. Norton & Company, 2007. 1872-2046. Print.

Turrell, J.W. Ancient Angling Authors. London: Gurney and Jackson, 1910. Print.

Walton, Izaak. “The Compleat Angler or the Contemplative Man’s Recreation.” The Compleat Angler. Ed. Jonquil Bevan. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1983. 2-163. Print.

Walton, Izaak and Charles Cotton. “Walton on His Own Times.” The Compleat Angler. New York: The Heritage Press, 1948.