The Potential for a Kidney Market in America

In the United States, the demand for kidneys has reached a critical point. Each year, approximately 125,000 patients are diagnosed with kidney failure, yet only a fraction—around 22,000—receive life-saving transplants (McCormick & Held, 2023). Every day, about 17 people die while waiting for a transplant that never comes (Eames et al., 2017). With 84 percent of individuals on the national transplant list awaiting kidney transplants, thousands are left enduring mandatory dialysis as their only option, hoping for a compatible donor before it’s too late (New Report Recommends…, 2022). Much like the contentious markets for guns, drugs, surrogacy, prostitution, or personal data, a potential kidney market stirs debate, touching on ethics, morality, justice, socioeconomic inequality, and the extent to which government intervention should shape such markets. These debates often reflect conflicting values and ideological perspectives, making any form of consensus difficult to achieve. However, the urgency of reaching a consensus on the legality and structure of a kidney market is particularly pronounced compared to other controversial markets due to the immediate and far-reaching implications it holds for human lives.

The severity of the kidney shortage crisis in the United States cannot be overstated; since the first successful kidney transplant in 1954, it has been the most needed organ for transplant (NSCF). Each year, between 5,000 and 10,000 Americans die prematurely due to the lack of available kidneys for transplant, while approximately 100,000 individuals remain reliant on dialysis—a grueling, life-sustaining treatment that, despite its necessity, is ultimately only a temporary solution (Held et al., 2015). For patients with end-stage kidney disease, dialysis is physically and emotionally taxing, often resulting in painful side effects such as hernias, intense muscle cramps, low blood pressure, chronic infections, and severe skin issues. Mental health challenges, including depression, anxiety, and fatigue, are also common, as the relentless cycle of treatments erodes patients’ autonomy and quality of life (Some Physical Side Effects of Dialysis and How to Prevent Them, 2020). Most patients undergo dialysis three times a week, with each session lasting four hours or more, demanding immense time and financial resources. The schedule disrupts work, social relationships, and personal well-being, while financial costs add another layer of burden. Even with insurance, patients often face high out-of-pocket expenses for treatment, medications, and frequent medical appointments, making it especially challenging for low-income individuals who may struggle to maintain regular sessions or cover associated healthcare costs.

Despite these sacrifices, the efficacy of dialysis is limited. Long-term survival rates are low, with only about 50 percent of patients surviving beyond five years on dialysis, a stark contrast to the 80 percent five-year survival rate for those fortunate enough to receive a kidney transplant (University of California San Francisco, 2019). Transplants not only offer patients a chance at a longer life but also an improved quality of life, free from the relentless physical discomfort and lifestyle restrictions imposed by dialysis. The disparity in outcomes between dialysis and kidney transplants underscores the urgent need for a solution to the kidney shortage crisis, especially as it disproportionately affects socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals. The inadequacies of the current system reveal a deeply rooted social issue, as low-income patients are more likely to experience interrupted care, financial strain, and greater risks associated with prolonged dialysis. Moreover, studies have shown that racial and ethnic minorities, as well as those with lower educational attainment and financial resources, are significantly less likely to be listed for renal transplantation before dialysis, further compounding health disparities (Kasiske et al., 1998). For these patients, the lack of available kidneys isn’t merely a medical setback; it reinforces a cycle of poverty and health inequity. This disparity reality amplifies the urgency of considering a regulated kidney market as a potential solution, where ethical concerns must be balanced with the imperative to alleviate suffering and extend life for thousands currently without options.

Despite the clear survival advantages of kidney transplants over dialysis, the United States prohibits financial compensation for kidney donors. This policy intensifies the challenges for those in need of life-saving transplants by limiting the pool of potential donors to purely altruistic individuals. While altruistic donation remains noble, the numbers show it falls far short of meeting demand. This disparity raises urgent questions about the impact a regulated kidney market may have in closing the gap. Supporters argue that a compensated kidney market incentivizes more donors, reduces wait times, and saves thousands of lives annually. Yet, a market also introduces complex ethical concerns. Critics fear exploitation, particularly among socioeconomically disadvantaged individuals who may feel pressured to sell organs due to financial need. Others highlight concerns about equity in transplant access, questioning whether a market-driven system might deepen existing health disparities by favoring wealthier patients.

The debate over a kidney market in America remains contentious, rooted in complex ethical questions about healthcare, socioeconomic disparities, and moral obligations. Beyond simple supply and demand, this issue requires balancing the urgent need to save lives with a commitment to dignity, fairness, and justice in healthcare. While opponents caution against the potential for exploitation and inequality, proponents argue that regulated compensation not only expands organ availability but also creates a framework that minimizes risks, ensures fairness, and protects vulnerable populations. With thousands of lives at stake, achieving consensus on this issue becomes critical. Legal and ethical frameworks around organ markets vary globally, with some countries adopting regulated systems that balance donor rights and recipient needs, though the U.S. has yet to fully explore a model tailored to its healthcare landscape. A balanced solution—addressing both the urgent demand for kidneys and the ethical concerns about compensation—presents a viable path to serving patients while upholding donor integrity.

Given the dire kidney shortage crisis in the United States, characterized by extensive waitlists, high mortality rates, and suboptimal treatment outcomes for patients on dialysis, the legalization of kidney markets emerges as a necessary and morally justifiable solution. Allowing financial compensation for kidney donors could significantly alleviate the shortage, save thousands of lives annually, improve healthcare equity, and enhance overall societal well-being.

Ethical and Moral Considerations

a) Lives saved versus the nature of a kidney market

By legalizing a kidney market, there would undoubtedly be an immediate increase in the number of kidneys available for life-saving transplants, far surpassing the limited supply provided solely through altruistic donations. However, widespread repugnance toward such a system creates a significant barrier between theoretical logical and practical implementation. A kidney market in the simplest terminology possible is when one individual undergoes surgery to donate a kidney to someone in need and receives monetary compensation in return. While this transaction may seem straightforward, this kind of market provokes three primary concerns: firstly, the view that body parts become commodities; secondly, concerns about inequality of access, as only the wealthy may afford to purchase kidneys, potentially leading to exploitation of the poor who are more likely to donate; and thirdly, apprehension regarding the decline in the quality of donated kidneys and associated safety risks.

The first, primary concern with a legal kidney market is that assigning monetary value to organs commodifies them, suggesting they hold the same economic worth as goods like food, precious metals, or natural gas. This view opposes the notion that organs operate as exchangeable, fungible objects in any market, asserting that commodification disregards their intrinsic value and erodes the reverence owed to the human body (Castro, 2003). While this perspective is emotionally compelling, it overlooks a stark reality: kidneys are already being bought and sold, but through an illegal, unregulated black market. Far from eliminating commodification, the current ban on compensation fuels a dangerous and exploitative underground trade. Estimates from the World Health Organization (WHO) indicate that approximately 10,000 kidneys are illegally traded each year, generating annual revenues between $840 million and $1.7 billion. This black market primarily serves wealthier buyers who can afford the high costs of illegal transplants, leaving vulnerable populations exposed to exploitation, trafficking, and even organ theft. When considering the financial aspects of legal transplants, it becomes clear that many already profit from the process—except for the donors themselves. In 2020, the average cost of a kidney transplant reached $442,500, covering pre-transplant procedures, organ procurement, hospitalization, medical care, and post-transplant medications (Wang & Hart, 2021; Bentley & Ortner, 2020). In this scenario, hospitals, physicians, and healthcare providers receive compensation at market rates, while donors remain the sole participants in this process who receive no financial benefit (Ng, 2019). Legalizing compensation for kidney donation not only reduces the influence of black markets but also allows for a more transparent and humane system that respects donor agency and provides essential safety measures. Making certain markets illegal rarely eradicates demand; rather, it drives the trade underground, as seen in industries like drugs, firearms, and alcohol. Legal kidney markets alleviate the black market by addressing the high demand through a regulated, safe, and ethically guided system. Ultimately, the argument against commodification confines human dignity to a narrow view, as respect for donors’ well-being thrives under rigorous protections. Rather than diminishing dignity, a compensated kidney donation system enhances it by valuing donors’ contributions, offering consent-based choice, and alleviating suffering. When handled ethically, compensation upholds human dignity, offering freedom, promoting health, and preserving life. Furthermore, if a donor’s consent justifies organ procurement in altruistic donations, the same justification extends to compensated scenarios as well (Castro, 2003).

The second common objection to a kidney market arises from concerns that wealthier individuals predominantly buy kidneys, while financially vulnerable individuals primarily supply them. While rooted in ethical concerns about exploitation, this argument overlooks the pressing realities of supply and demand in the current transplant system. Today, with demand vastly outstripping supply, thousands of patients languish on waitlists or endure years of life-disrupting dialysis, many ultimately dying without receiving a transplant. A regulated kidney market expands the supply of kidneys, reducing wait times and saving lives by introducing a new source of donors participating under fair, transparent terms. Critics contend that a kidney market disproportionately affects poorer individuals, who may feel financially pressured to sell their kidneys. However, banning compensation entirely fails to eliminate exploitation; instead, it preserves the status quo, where those in need face limited options, and the burden of shortages falls heaviest on the most vulnerable. Society already accepts financially compensated risks in high-stakes roles—such as firefighters, construction workers, and military personnel—where individuals assume danger for the benefit of others. Similarly, compensating kidney donors honors their contributions as acts of courage and altruism, akin to those who risk their safety in other fields. Financial incentives within a regulated framework boost organ availability while establishing protections that prevent exploitation, ensuring that donors remain informed and supported throughout the process. Addressing concerns about exploitation requires a focus on the conditions that drive individuals to consider kidney donation. True concern for the financial pressures influencing these decisions should drive efforts to strengthen social safety nets and economic support systems to alleviate financial desperation. Prohibiting a kidney market does not solve these underlying issues but sidesteps them. Implementing ethical and protective standards within a regulated kidney market offers a compassionate solution that respects individual agency while mitigating exploitation risks. In this way, a well-regulated market balances supply and demand, honors donor contributions, and provides life-saving options to those in dire need, ultimately creating a more equitable and humane system overall (Ng, 2019).

Thirdly, the concern arises that the introduction of kidney markets may compromise the quality of donated kidneys and raise safety issues for both donors and recipients. The underlying fear is that monetary incentives could lead donors to falsify medical records to secure payment, potentially jeopardizing the integrity of the donation process. This could mean that while more kidneys become available, the quality of donated organs might drop compared to those given altruistically. However, rather than viewing this as a reason to oppose the establishment of a kidney market, it should prompt the implementation of stringent procedural guidelines to ensure the market operates safely and ethically. As for safety concerns for donors in general donating a kidney for a life altering check, research from Singapore General Hospital (SGH) and Duke-NUS Medical School suggests otherwise. Their study, spanning from 1976 to 2012 and involving approximately 180 living kidney donors at SGH, revealed that donors lead healthy lives with minimal risks. The risk of complications from surgical procedures for kidney transplants ranges from 1 percent to 5 percent, with the risk of death being as low as one in 3,000 (0.033 percent), comparable to that of an appendix operation. Furthermore, individuals born with only one kidney, constituting one in 2,000 people, lead normal lives, indicating that living kidney donation is a safe option. Dr. Tan Ru Yu, the lead author of the study, emphasized the importance of living donation, particularly for end-stage kidney failure patients who face long waits. These findings underscore the safety and viability of living kidney donations, providing reassurance amidst concerns about the establishment of kidney markets (Khew, 2016). However, if kidney markets were legalized, skepticism should absolutely prevail until the system proved to be built on strong ethical grounds reflected in rigorous and highly standardized processes.

b) Rationality of choice and individual choice

Within the current altruistic system, individuals possess the autonomy to decide whether to donate a kidney or not. While this remains true under a kidney market system, valid arguments suggest that the rationality of individual choice undergoes a significant shift compared to an altruistic one. To explore this claim through an economic lens, picture two individuals within the existing legal framework: altruistic kidney donations are permitted, while financial incentives remain illegal. One person is a potential kidney donor, and the other requires a kidney transplant. Assuming rationality4 and under the current system, wherein donating a kidney entails health risks and the prevailing wisdom is that “two kidneys are better than one,” a donor would only logically choose to proceed if the overall welfare gains offset the potential negatives5. It’s reasonable to assume that most donors are more inclined to help someone who has a significant impact on their life, such as a parent, sibling, relative, or close friend, as the emotional well-being derived from preventing the loss of such an influential person can outweigh the possible side effects of kidney donation. However, donating a kidney to a stranger or someone less influential to their life may not be considered a rational choice for the average donor.

Now, contrast this with a scenario where financial incentives come into play. Suppose the compensation offered for a kidney donation is $45,000, a number calculated by the American Journal of Transplantation (Held et al., 2015). Suddenly, rationality takes a different form. With the national average wage index in 2022 standing at $63,765.13 according to the Social Security Administration, the average person becomes highly incentivized to consider kidney donation in various situations. Financial strain, debt accumulation, and other life-altering circumstances now render kidney donation a rational choice for many individuals. For instance, individuals facing eviction due to financial hardships or struggling to cover medical bills for a loved one’s illness may find donating a kidney a viable solution to alleviate immediate financial burdens. Additionally, those seeking to pursue higher education but burdened by student loan debt may see kidney donation to alleviate their financial strain and secure a brighter future.

Practical benefits

a) Intuitive benefits

There are many potential benefits of opening a kidney market in America, the first and most obvious being that an undoubted increase in supply of kidneys would alleviate the United States’ urgent kidney crisis. More kidneys vastly reduce wait times for transplant candidates and thoroughly improve healthcare outcomes for those in need of kidney donations. As previously established, organ trafficking generates an estimated $840 million to $1.7 billion annually, primarily involving kidneys, with approximately 10,000 kidneys exchanged each year. These figures underscore the significant demand diverted to illicit markets, especially when compared to average wait times of 4 years in Canada, 3.6 years in the U.S., and 2 to 3 years in the U.K. for legal kidney transplants (ACAMS today, 2018). Lowering wait times through the establishment of kidney markets would substantially diminish the need to resort to purchasing kidneys from the black market and preserve more lives.

b) Calculated benefits

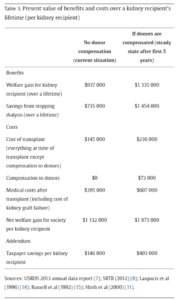

The American Journal of Transplantation conducted a comprehensive cost-benefit analysis on government compensation for kidney donations, highlighting the potential benefits of establishing a kidney market. The study revealed substantial cost savings to society, amounting to about $1.45 million per recipient, by eliminating the need for expensive dialysis treatments for kidney recipients. Moreover, the study estimated the monetary value of the improved longevity and health of kidney recipients to be approximately $1.3 million per recipient. These findings demonstrate that the benefits of kidney transplantation far exceed the proposed compensation of $45,000 per kidney. Overall, society could experience significant benefits, including saving thousands of lives annually and improving the quality of life for over 100,000 individuals undergoing dialysis, resulting in a net benefit of approximately $46 billion per year. By extension, taxpayers could save approximately $12 billion annually. The study also indicates that transitioning from a system reliant on dialysis to one in which dialysis is no longer needed could increase the life expectancy of transplant recipients by an average of 7 years. Furthermore, the cost of kidney transplantation– which is approximately $145,000 with donors receiving no compensation– pales in comparison to the substantial benefits gained from stopping dialysis. This analysis underscores the importance of government compensation for kidney donors, as it could significantly improve the welfare of transplant recipients and society while offering substantial savings for taxpayers (Held et al., 2015) (look in Appendices Figure 3)7. However, it’s important to acknowledge that the establishment of a kidney market in America comes with uncertainties and potential negative side effects. While this analysis offers a theoretical framework for the potential benefits, the actual outcomes remain speculative. Despite the uncertainties, these potential benefits of establishing a kidney market as outlined in this analysis massively outweigh the potential costs. The ability to save thousands of lives, improve healthcare outcomes, and achieve substantial cost savings for society undeniably warrants further exploration.

Alternative Solutions

The current altruistic donation system for kidneys relies on voluntary donations from living and deceased donors to address the growing demand for transplants. Despite efforts to optimize allocation through innovations such as paired exchanges and transplant chains, significant challenges remain in balancing efficiency and equity. The system grapples with a persistent supply-demand mismatch, leading to thousands of individuals being removed from the waiting list annually due to illness or death (Walsh, 2021). A plethora of other systems have been pitched to replace this current system in America, including systems such as but not limited to the following:

- Paired exchange programs allowing incompatible donor-recipient pairs to exchange kidneys with other pairs, increasing the chances of finding a match.

- Chain exchanges involving a sequence of transplants where each donor’s kidney goes to a recipient, and a new donor joins the chain.

- Presumed consent programs adopted by some countries in which individuals are considered organ donors by default unless they explicitly opt out.

- Paid kidney markets through which advocates propose either individual or government regulated processes allowing financial compensation for kidney donation.

- Individual Market: Individuals could sell their kidneys directly to recipients or through intermediaries.

- Government-Regulated Market: The government oversees transactions, ensuring fairness and preventing exploitation.

- Non-monetary incentives such as tax credits, health insurance benefits, or tuition assistance for living donors to encourage donation.

My Recommendation: Implementation and Regulation

My proposed recommendation for reforming the kidney market system in America centers on the establishment of a regulated government market for kidney donations, alongside the integration of monetary and non-monetary incentives. While the altruistic system is commendable, its efficacy may be limited in a society where voluntary kidney donations are insufficient to meet the overwhelming demand. The disparity between those in need of a kidney transplant and those receiving one is simply too vast to maintain the status quo. While I support the notion of individuals freely choosing to donate their kidneys under appropriate circumstances, I advocate for the implementation of additional mechanisms to address the pressing needs of a broader population awaiting kidney donations. Moreover, I believe that tackling this issue could yield numerous positive outcomes for America’s social welfare.

To begin with, the kidney market should transition towards a government-regulated system for organ donations. A primary concern regarding paid organ donations is the potential for exploitation, where only the wealthy can afford to purchase kidneys while the poor are more likely to donate. Iran’s pioneering example of a regulated kidney market provides a valuable blueprint. The Iranian model has significantly increased transplant volumes and ensured access to kidney transplantation for most Iranian candidates, regardless of socioeconomic status. Despite facing challenges and necessitating adjustments over time, the Iranian medical community has continuously refined the system.

Noteworthy aspects of this model include the establishment of a legal framework for enforceable contracts between donors and recipients, the provision of informed consent from donors and their families, licensing of NGOs to facilitate transplant agreements, and comprehensive data collection to evaluate the system’s effectiveness. Additionally, government funding of all transplant-related medical expenses and the requirement for surgeries to be performed by qualified teams in university hospitals ensure quality and accessibility (Bastani, 2019). While the Iranian Model is not without its flaws, it demonstrates the potential for developing countries to enhance the efficiency, safety, and accessibility of kidney donations for their citizens. This sets a precedent for developed countries like the US to follow suit.

The Iranian Model provides a strong foundation, but the implementation of such a system in the US would require careful adaptation and consideration of the country’s unique circumstances. Despite its successes, challenges remain, and lessons must be learned to tailor the approach to the American context. However, key components of the Iranian Model, such as the legal framework, informed consent protocols, NGO assistance, comprehensive data collection, government funding, and quality standards present valuable insights for shaping a kidney market in the US.

These elements serve as critical first steps towards the establishment of an efficient and ethical kidney market that prioritizes the welfare of donors and recipients alike. Some additional ideas worth exploring are having other non-monetary incentives for kidney donors. Due to the fact that our country is considered a liberal welfare state (meaning there is low decommodification, high stratification, most are privately insured, etc), I believe the US could take this opportunity to start reflecting the general want for better welfare provisions than are previously enjoyed by many citizens (Sainsbury, 2012). Instead of full monetary incentives, the government could alternatively provide lifetime guaranteed free healthcare, debt payoff credits, tuition assistance, or housing assistance that could be of higher value than cash. Additionally, it’s hard not to recognize the magnitude to which different socioeconomic classes would benefit from an incentive driven market system. The top 10 percent of earners control 66.9 percent of the total wealth in the US and the lowest 50 percent own a mere 2.5 percent, exacting that extra measures could be added to account for socioeconomic status. This could include basing compensation (both monetary and non-monetary) on personal financial circumstances, allowing those deemed in harsher personal financial circumstances to benefit more than those in better standings. This would address some of America’s systematic and detrimental class issues (Statista Research Department, 2024).

Other systemic issues within America worth addressing in this proposed policy include the pervasive racial, gender, and sexual orientation biases ingrained in the healthcare system. These biases contribute to significant disparities in health outcomes. For instance, black women are three times more likely to die during pregnancy than white women, a stark reflection of systemic racism within healthcare (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2023). Similarly, the LGBTQ community faces discrimination and exclusion from certain healthcare opportunities; for example, it wasn’t until 2015 that gay men were legally allowed to donate blood (Mazer, 2023). These examples only scratch the surface of the profound inequities experienced by marginalized groups in accessing healthcare. A simple internet search reveals a multitude of disparities, with marginalized individuals consistently receiving substandard care compared to their privileged counterparts. Given this reality, it’s imperative to address these concerns when considering the establishment of a kidney market. To mitigate these biases within the healthcare system, several measures must be integrated into the proposed kidney market policy. Firstly, the implementation of an extensive database to collect and analyze demographic data on kidney donation and transplantation outcomes is crucial for identifying disparities and trends related to race and sexual orientation. Utilizing this data to inform targeted interventions and policy changes aimed at reducing disparities and promoting equity in access to kidney healthcare services is paramount. Additionally, ensuring diverse representation on decision-making bodies responsible for overseeing the kidney market, including committees, advisory boards, and regulatory agencies, is essential. Representation from marginalized communities can help ensure that policies and practices are inclusive and address the needs of all individuals, regardless of race, gender, or sexual orientation.

Concluding Remarks

The establishment of a kidney market in America offers a multifaceted solution to the urgent kidney shortage. Transitioning to a government-regulated system for organ donations, with a mix of monetary and non-monetary incentives, could significantly increase the supply of available kidneys for transplantation while addressing ethical, moral, and systemic issues within the healthcare system. The potential benefits of a kidney market are substantial, including saving thousands of lives annually, improving healthcare outcomes, and achieving considerable cost savings for society. Although uncertainties and potential negative side effects exist, comprehensive cost-benefit analyses indicate that the benefits outweigh the costs.

Alternative solutions such as paired exchange programs, presumed consent laws, and non-monetary incentives should be considered but integrated within a comprehensive kidney market framework. Furthermore, addressing systemic biases within the healthcare system, including racial, gender, and sexual orientation biases, is paramount and must be incorporated into the proposed kidney market policy through measures such as data collection and diverse representation on decision-making bodies. Overall, the establishment of a kidney market in America represents a necessary and morally justifiable solution to the kidney shortage crisis, with the potential to save thousands of lives and improve the quality of life for countless individuals awaiting life-saving transplants.

Appendices:

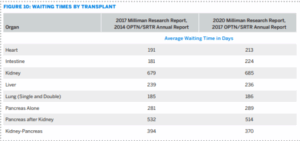

Figure 1:

(Bentley & Ortner, 2020)

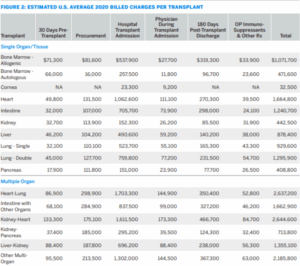

Figure 2:

(Bentley & Ortner, 2020)

Figure 3:

(Held et al., 2015)

References:

ACAMS today. (2018, June 26). Organ Trafficking: The Unseen Form of Human Trafficking – ACAMS Today. Acamstoday.org. https://www.acamstoday.org/organ-trafficking-the-unseen-form-of-human-trafficking/

Andrews, P., Ausbrook, M. K., Brown, A., Carroll, C., Emmanouilides, M., Fischer, L., Green, A., Herbert, J., Nefedova, Y., Obermaier, E., Reinhart, M., Tam, S., & Wagner, E. (n.d.). The Value of a Human Life. Iu.pressbooks.pub, 3. https://iu.pressbooks.pub/perspectives3/chapter/the-value-of-a-human-life/#:~:text=The%20illicit%20organ%20trade%20is

Bastani, B. (2019). The Iranian model as a potential solution for the current kidney shortage crisis. International Braz J Urol, 45(1), 194–196. https://doi.org/10.1590/s1677-5538.ibju.2018.0441

Bentley, T. S., & Ortner, N. (2020). 2020 U.S. organ and tissue transplants: Cost estimates, discussion, and emerging issues. In Milliman. Milliman, Inc. https://www.milliman.com/en/insight/2020-us-organ-and-tissue-transplants#

Castro, L. D. de. (2003). Commodification and exploitation: arguments in favour of compensated organ donation. Journal of Medical Ethics, 29(3), 142–146. https://doi.org/10.1136/jme.29.3.142

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2023, April 3). Working together to reduce black maternal mortality. Www.cdc.gov. https://www.cdc.gov/healthequity/features/maternal-mortality/index.html

Eames, K. C., Holder, P., & Zambrano, E. (2017). Solving the kidney shortage via the creation of kidney donation co-operatives. Journal of Health Economics, 54(0167-6296), 91–97. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jhealeco.2017.04.001

Folger, J. (2024, February 23). Non-Governmental Organization (NGO): Definition, Example, and How It Works. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/ask/answers/13/what-is-non-government-organization.asp#:~:text=A%20non%2d Governmental%20organization%20(NGO)%20is%20a%20group%20that

Ganti, A. (2023, May 27). Rational Choice Theory. Investopedia. https://www.investopedia.com/terms/r/rational-choice-theory.asp

Held, P. J., McCormick, F., Ojo, A., & Roberts, J. P. (2015). A Cost-Benefit Analysis of Government Compensation of Kidney Donors. American Journal of Transplantation, 16(3), 877–885. https://doi.org/10.1111/ajt.13490

Iran: country data and statistics. (n.d.). Worlddata.info. https://www.worlddata.info/asia/iran/index.php#:~:text=According%20to%20the%20 definition%20from

Kasiske, B. L., London, W., & Ellison, M. D. (1998). Race and socioeconomic factors influencing early placement on the kidney transplant waiting list. Journal of the American Society of Nephrology: JASN, 9(11), 2142–2147. https://doi.org/10.1681/ASN.V9112142

Khew, C. (2016, November 30). Living donor not at higher risk of kidney failure: Study. The Straits Times. https://www.straitstimes.com/singapore/health/living-donor-not-at-higher-risk-of-kidney-failure-study

Mazer, B. (2023, February 2). The FDA’s New “Don’t Say Gay” Policy for Blood Donation. The Atlantic. https://www.theatlantic.com/health/archive/2023/02/fda-blood-donation-policy-homophobic-restrictions/672922/

National Average Wage Index. (2022). Www.ssa.gov. https://www.ssa.gov/oact/cola/AWI.html#:~:text=The%20national%20 average%20 wage%20index

New Report Recommends Changes to U.S. Organ Transplant System to Improve Fairness and Equity, Reduce Nonuse of Donated Organs, and Improve the System’s Overall Performance. (2022). Nationalacademies.org. https://www.nationalacademies.org/news/2022/02/new-report-recommends-changes-to-u-s-organ-transplant-system-to-improve-fairness-and-equity-reduce-nonuse-of-donated-organs-and-improve-the-systems-overall-performance

Ng, Y.-K. (2019). The Case for Legalizing Kidney Sales (Y.-K. Ng, Ed.). Cambridge University Press; Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/core/books/markets-and-morals/case-for-legalizing-kidney-sales/43C44F07546E26CC0736DCCD308234D1

Organ Transplants. (n.d.). National Stem Cell Foundation. https://nationalstemcellfoundation.org/glossary/organ-transplants/

Sainsbury, D. (2012). Liberal Welfare States and Immigrants’ Social Rights. 23–52. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780199654772.003.0003

Some physical side effects of dialysis and how to prevent them. (2020). Davita.com. https://www.davita.com/treatment-services/dialysis/on-dialysis/some-physical-side-effects-of-dialysis-and-how-to-prevent-them

Statista Research Department. (2024, April 11). Wealth distribution U.S. 2023. Statista. https://www.statista.com/statistics/203961/wealth-distribution-for-the-us/#:~:text=U.S.%20wealth%20distribution%20Q3%202023&text=In%20the%20third%20quarter%20of

Understanding Commodities | PIMCO. (n.d.). Pacific Investment Management Company LLC. https://europe.pimco.com/en-eu/resources/education/understanding-commodities#:~:text=Commodities%20are%20raw%20materials%20used

University of California San Francisco. (2019). Statistics | The Kidney Project | UCSF. Pharm.ucsf.edu. https://pharm.ucsf.edu/kidney/need/statistics

Mccormick, F., & Held, P. (2023). How to End the Kidney Shortage – ProQuest. Www.proquest.com. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2794183984?pq-origsite=summon&sourcetype=Magazines

Walsh, D. (2021, October 15). A beautiful application: Using economics to make kidney exchanges more efficient and fair. Stanford Graduate School of Business. https://www.gsb.stanford.edu/insights/beautiful-application-using-economics-make-kidney-exchanges-more-efficient-fair

Wellbeing and Welfare – Econlib. (2019). Econlib. https://www.econlib.org/library/Topics/College/wellbeingandwelfare.html