Isolation at Will: Five Hours in Emergency Psychiatry

Abstract

Graham Burri writes about his shadowing experience in UNC’s Psychiatric Ward. He profiles two individuals who are making extended stays in the ward, highlighting the benefits that come from their treatment.

CHAPEL HILL, N.C.― At one of the most active working university hospitals in the world, most are hospitalized for the kind of day-to-day injuries that are expected in any college town. The facilities of UNC Medical Center are sprawling—an easy place to get lost in. It exists as its own isolated world, sequestered from the town by bedside manner and professional courtesy. It operates twenty-four hours a day, seven days a week, three-hundred-and-sixty-five days a year. It has its own power and water supply. It is less like a facility for simple treatment, and more like a medieval fortress ready to resist a siege. None of the staff seem to be bothered by the imposing scale of the place—they deal in matters of life and death.

Buried within the hospital is Emergency Medicine, the department responsible for treating the most severe—and potentially deadly—wounds. The majority of cases—cuts, burns, alcohol poisoning—are quickly treated and dismissed. Nevertheless, as one of only five facilities in the state designated a Level 1 trauma center, it contains the staff and equipment necessary to treat even the most severe bodily injuries. In Emergency Medicine, nearly all patients leave—some through the morgue—within about 48 hours. Tucked away in the bowels of the hospital complex, however, is a windowless ward for patients with conditions that are more than skin-deep, the kind of patients who cannot get stitches for their problems. This is the Emergency Psychiatric ward, an alien place where patients stay cloistered for days or even weeks. There’s no telling how long they will need to stay, or even if their stay will help them recover.

4:30 P.M.

It’s a Friday afternoon, and, as such, conditions at the UNC hospital are slow. Save for the regular trickle of inebriated students, most of the staff prepare for the arrival of the night shift personnel. Doctors and residents walk quickly from place-to-place, wearing ivory lab coats and stern expressions of absolute focus. Most of the non-urgent wards are easily accessible, with pediatrics, neurology, oncology, and women’s health occupying the forward facade of the main hospital building, which is lit up by a set of enormous plate-glass windows. The emergency departments are another story entirely. They occupy the rear of the main building, so as to be able to transfer patients from ambulances to hospital beds as quickly as possible with the lowest chance of interruption or interference. The front of the hospital can afford to take its time with pleasantries like reception desks, windows, and potted plants. The back, given the choice between aesthetics and utility, ditched the fluff and focused on what matters—its patients.

This attitude is mirrored in the personnel of the emergency department, too. The chief of the Emergency Psychiatry division of UNC Medical Center exudes an aura of professionalism, although it is tempered by the occasional joking remark which seems to be a characteristic of all good doctors. For someone who manages the mental health of dozens of patients in extreme situations, she’s remarkably laid-back—at least at first. However, the nurses and doctors of UNC emergency psychiatry are like coiled springs ready to burst into action at any moment. The emergency psychiatric department is a place of extremes—that sense of bizarre calm can, at any moment, be replaced with a flurry of agitated activity. This binary state seems to extend to the patients as well. The doctor’s categorization of patients is essentially based on the same idea; they are either calm and manageable or agitated and unmanageable. Given the fragile mental state of many of the patients, especially those who are hospitalized against their will, the quiet calm of the psychiatric ward is enforced by a set of nurses who keep an eye on the ward. They watch twenty-four hours a day from behind a thick panopticon of reinforced glass and a set of three code-accessed metal doors. The staff of emergency psychiatrics are willing to enforce the Hippocratic Oath by any means necessary, even if that means creating a system that wouldn’t be out of place in a prison.

5:00 P.M.

It’s quiet in the psychiatric ward as nurses whisk wordlessly from place to place, carrying clipboards and medical tools throughout the facility. The chief psychiatrist and a nurse holding a stack of paperwork lead the way to one of the patient rooms at the end of the hall. Rooms for individual patients are only semi-private, consisting of roughly 7 foot by 10 foot alcoves cordoned off from the central corridor by sterile vinyl curtains. There’s a couch, a single bed, and a television. Everything about these rooms is designed to be as durable, sterile, and replaceable as possible. The walls are a dull beige, with the only adornment an occasional mounting point for various medical equipment. There’s nothing in these rooms that a patient could use to harm themselves, either—even the televisions are encased in a kind of cage. Likewise, the entire ward is bereft of windows or any means of telling the time of day. Deep within the bowels of the hospital, it’s as if time seems to move differently.

5:30 P.M.

The chief psychiatrist introduces one of her patients, GG, a semi-regular case. Before she enters his room, she gives a quick warning: “He may look a little tough, but he’s really a sweetheart.” The first part of her assessment is certainly correct. He’s an older man, about 40, with a strong upper body, a bushy beard, and an enormous bull-ring pierced into his philtrum. He looks like he could bench-press a horse. However, he’s in a good mood—he’s about to be discharged after a stay of about a week in the ward. Like a number of patients, GG is here voluntarily. He chose to admit himself in order to detox after an alcohol and drug binge. Cases like his are becoming more and more common in wards like this, as the opioid crisis affects more and more people. Unlike others, however, GG had the presence of mind to seek medical help before it was too late.

The patients in Emergency Psychiatry for substance abuse issues exist in a bizarre limbo. Most, like GG, have chronic problems with substances but cannot afford the expensive outpatient rehabilitation centers used by the wealthy. Given the relatively stable nature of substance abuse cases when compared with those with more extreme psychological issues, many of these patients find themselves voluntarily in emergency departments, waiting out their withdrawal symptoms in an environment that is, at the very least, drug free. However, these departments aren’t drug addiction clinics, and can only help patients in the short-term. These departments do not have the necessary specialists, time, or money to change patients’ attitudes to prevent future substance issues. When they leave the department’s care, it’s all too easy for them to slip into dangerous relapses.

Despite his intimidating appearance, GG is open and happy to talk to somebody. He explains that the solitude of the psychiatric ward is felt more acutely as a result of the professional mannerisms of the doctors. “You can’t really talk to them,” he continues “they’re here to help, but they’re very busy.” GG is highly familiar with the psychiatric ward. He’s been a patient here a number of times, not only due to his problems with alcohol and drugs. GG also suffers from severe epilepsy and a cyst on his temporal lobe. Being in the ward means that if one of these conditions becomes more serious, he can easily receive help. Given that he lives in a rural area, it makes more sense for him to detox in the hospital, where medical care is more easily accessible. Cases like GG’s are more common than people think. Most patients in the emergency psychiatric ward are there for less than 24-hours at a time. People like GG are the ones who fall through the cracks: the chronic patients who stay for weeks at a time, several times a year.

This is one of the areas in which mental health treatment is fundamentally different from physical treatment. Unless an injury is particularly bad, most patients suffering from physical illnesses don’t have to stay in the hospital at all, and doctors can draw from an enormous pool of past data to determine how quickly they’re likely to recover. Mental health emergencies, on the other hand, are often manifestations of chronic, lifelong conditions. Given the highly individual nature of each person’s mental illness, it is difficult for doctors to know how long it may be necessary to keep someone confined to the hospital, or even if that will help. It’s easy to see how the windowless and sterile confines of the emergency psychiatric ward could make a person’s condition worse rather than better. Despite the difficulties involved in treating patients like him, GG is grateful: “They do their best,” he insists. “And that’s all they can do.”

7:00 P.M.

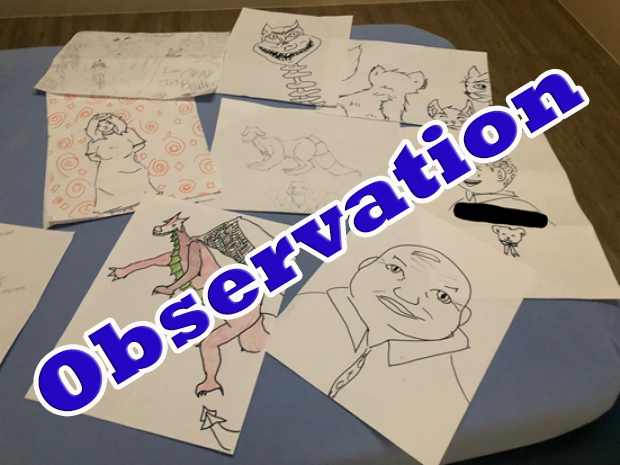

As the night wears on, the lights dim and the dull murmur of conversation among patients and medical staff begins to die down. Without any way to reliably tell the time or anything interesting to do besides watch television, most patients tend to go bed earlier than they would have on the outside. One exception is the next patient, ZA, a woman in her early 20s, who, like GG, is a voluntary attendee of the ward. Unlike GG, however, she doesn’t sport any bovine-inspired body modifications. The doctor makes the introductions before ducking out to attend to a loud and disorderly patient further down the hall. ZA has been in the emergency psychiatric ward for four days, but she is energetic and cheerful despite her environment. “You get used to it.” she explains. ZA is a frequent patient at the UNC hospital because she suffers from chronic manic-depressive bipolar disorder: a condition in which the afflicted goes through periods of intense emotional highs, known as manic periods, followed by extreme sadness, known as depressive periods. ZA’s condition is especially severe, and has resulted in suicide attempts on more than one occasion, starting when she was 10. In order to protect her from herself, ZA comes to the hospital voluntarily about every two weeks or so when she switches from a manic state to a depressive one. From her appearance and mannerisms now, however, one would never know that she had any kind of mental health problems at all. With small, cheerful brown eyes perched behind a pair of wire-rim glasses, she seems more genuinely happy in the emergency psychiatric ward than most people do in the outside world. Sitting on the center of the sterile medical bed, she’s surrounded by a plethora of deliberately unsharpened writing utensils and half-finished sketches and drawings. “Aside from my family,” she says, “art is my biggest passion in life.” ZA hopes to one day make her art into a full-time career, but her condition makes that difficult. “I had to drop out of art class again when I hit my [depressive] episode,” ZA continues. “Raising a young child is hard enough, but finding time for class on top of depression was just too much.”

Unlike GG, who seemed to view his stay in the ward as a necessary evil, ZA prefers to think of it as more of a vacation. She doesn’t have cable, so she appreciates the ability to catch up on shows when she’s in the hospital: “I don’t have ABC, but I love this show [Ghost Adventures]. Although I can’t stand the daytime news channels. It’s just too stressful to keep up with everything happening in the world.” A few minutes later, a nurse arrives with a tray of food for ZA’s dinner. It’s surprisingly elaborate: shrimp and grits served with bread and juice. The only complication is that she didn’t order shrimp and grits, and has never even tried them. ZA doesn’t hesitate, though. She dons an enthusiastic smile and eats a bite before suddenly stopping with a somewhat opaque look on her face. After a few moments, she breaks into an unabashed grin and remarks “This is incredible!” Even in the hospital, ZA insists that trying new things is vital to being more mentally healthy. “If you just stay in your comfort zone,” she muses between spoonfuls of shrimp, “you’ll never experience a lot of the good in the world.” Even coming out of a deep depression, ZA maintains an optimistic demeanor. As a nurse arrives to clean up from her dinner and issue discharge papers, she issues a parting remark: “Life is always worth living. Never forget that.”