The Mental Health Gap: Addressing Racial Disparities in Mental Health Care at Predominantly White Universities

In my short time attending the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, a predominately white institution (PWI), I have already begun to realize the academic pressures and high-stress environment. As a Black undergraduate, there is a shocking lack of resources and support for Black students regarding mental health and academics. Today, Black students at PWIs experience higher risks for symptoms of anxiety and depression than White students (Lomotey, 2010). Racial disparities in support for Black students at PWIs show the inherent inequalities in American society that have unfortunately seeped into the American higher education system.

Commonly seen as the key to social mobility, higher education provides opportunities for people of color to create social and financial capital. However, roadblocks, like poor mental health services at PWIs work against the motion for social progress. Increased risk of chronic mental health issues also causes Black academic performance to suffer. If students of color cannot perform at the same level at white institutions due to systemic issues, colleges fail to provide the education students derserve,

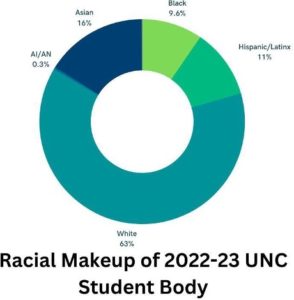

Post-secondary schools like the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, the University of California Los Angelesare high profile PWIs and will be the focus of this research study. At PWIs, 50% or more of the student body consists of white students. This skewed ratio is rooted in the deeply segregated history of colleges in America. Most established schools are historically white institutions that made their name by excluding women and people of color from attending.

According to UNC’s Common Data Set, the 2022 student body is 54% white and 8% Black, compared to 80% white in 2000 (Common Data Sets). While the student body is getting more diverse, the interests of the school remain the same. They aim to serve the white majority, ignoring the experiences and adversity faced by minority students on campus.

So, if PWIs are built to serve the needs and interests of white students, why do minority students choose to attend PWIs instead of HBCUs (Historically Black Colleges and Universities) or HSIs (Hispanic Serving Institutions)? While Black students may prefer to attend HBCUs, factors such as the cost of tuition, resources, and connections. In exchange, many students trade much of the social comfort they would experience at an HBCU for the opportunities they have at PWIs.

This phenomenon leads to a larger question: how do academic pressures and campus environment impact the mental health and academic performance of undergraduate students at PWIs?

Outlining the problem

There are five primary causes and catalysts of high-risk levels for mental illness in Black undergraduates: 1) microaggressions, 2) racial isolation and non-Black spaces, 3) White Institutional Presence and White Racial Frames, 4) Imposter Syndrome, and 5) a lack of mental health resources and medical mistrust. By understanding these root causes for Black students’ discomfort and increased mental health issues on campus.

Microaggressions, as defined by Powell, “are daily behavioral, verbal, or environmental indignities that involve people’s mixed heritage status” (Powell, 2021, p. 12). Microaggressions are small interactions that often negatively display racial bias. Typically, they create a more isolating and exclusive environment that objectifies and exoticizes the experiences of people of color. In a university setting, this mostly occurs with professors and peers. Unfortunately, as a support system and resource, peers and professors are often vital to success at this level.

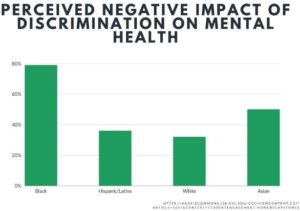

Many of these microaggressions stem from harmful stereotypes that paint Black students as lazy and unworthy of their place at the university. A 2013 study found that students who experience more racial microaggressions were more susceptible to mental health issues like depression, anxiety, and suicidal ideation (Torres-Harding et al., 2018, p. 132). Pictured right is a poll of Black student perceptions of discrimination on their mental health.

It also was likely to decrease levels of self-efficacy, which is how much a person believes in their abilities to complete tasks such as an exam or essay and increase self-destructive behaviors such as binge drinking.

In a 2018 study, professors of health and human sciences Clark and Mitchell highlight Black American’s experiences with microaggressions in the 2018 study. Black Students were interviewed and asked to discuss microaggressions at their midwestern PWI. (Please note that each student’s identity was protected when surveying them)

“If I’m on the bus and everybody’s standing up, but there is an open seat right next to me, but nobody sits down next to me, that’s a micro-aggression. That is the worst one ‘causes that happens every time I get on the bus, and I don’t get it ‘cause I’ll sit down next to you. I don’t care. Like, you’re a person but people, they don’t do it and I’m like, ‘Am I scary’” (Clark and Mitchell, 2018, p. 82).

“The most stressful thing as a student of color is just knowing that there are people in your class who are going to expect more out of you, whether it be dumb or intelligent. It’s just the fact that, you know, the first thing that come out of your mouth in that class, you’re judged on it no matter what” (Clark and Mitchell, 2018, p. 82).

“Having White professors and being a Black female student, it’s a lot of contrast there because of the whole White supremacy, male dominancy type of thing. And it’s like I already got two odds against me, I’m Black and I’m female. So, it was like a constant battle of me showing my professor, ‘You might be my professor, but you’re not superior to me’” (Clark and Mitchell, 2018, p. 83).

Problem 2) Racial Isolation and Lack of Black Spaces

At predominantly white institutions, there are very few spaces for Black students to inhabit. While student clubs such as Black Student Unions or Black Greek Life provide some structure and comfort to many students, not all students feel that they create the same sense of the environment as attending an HBCU. The lack of predominantly Black spaces on campus creates a sense of racial isolation that can negatively impact Black mental health and academic performance (Grier-Reed, 2018, p. 80). Racial isolation is when a student is one of the very few members of your own race in a predominantly white or monoracial environment. This often correlates with feeling like one must educate others on their experience and concepts of race and discrimination.

Campus climate plays a large role in the well-being and mental health of Black undergraduates. Clark and Mitchell define campus climate as “consist[ing] of the attitudes, behaviors, and standards of students, faculty, and staff members regarding the level of respect for individual needs, abilities, and potential” (Clark and Mitchel, 2018, p. 73). For minority students, campus climate is heavily impacted by the racial demographic of their peers, instructors, and other figures of authority on campus. Black students surveyed in this study described the campus environment as hostile, unwelcoming, and uncomfortable (Clark and Mitchell, 2018, p. 68). In contrast, white students reported a more positive and friendly environment.

Problem 3) White Racial Frames

The third cause is White Racial Frames (WRF), defined by Grier-Reed as “a set of cultural narratives and symbols based in White supremacy and anti-blackness that shape perception, ideologies, and even emotions in U.S society” (Grier-Reed, 2018, p. 65). Since PWIs adhere to white racial frames, they create hostile and unwelcoming environments for students of color. In addition to WRF, PWIs have a White Institutional Presence (WIP). Essentially, WIP is how white racial frames are institutionalized in higher educational settings. In predominantly white spaces, whiteness is equated with power and superiority, which assumes that minority students wish to adhere to white standards. PWIs enforce the white racial frames through curriculums, class discussions, textbooks, and the erasure of people of color in history.

The lack of diversity in the curriculum makes it harder for students of color to fit into predominantly white spaces, where Black experiences are ignored. Grier-Reed explains that white racial frames are seen through “inferior treatment and internalized racism including colorism, self-hate, and low expectations by educators and others”. Both WRF and WIP take a toll on the mental health of Black students who encounter them through emotional and cognitive labor. Essentially, WRF has stereotyped and created the narrative that Black students as lazy and inferior to their white peers. When defying WRF, white students and staff must undertake significant cognitive and emotional labor to avoid further stereotyping and discrimination.

Problem 4) Imposter Syndrome

The inherent value of whiteness at PWIs often leads Black students to question their place and their accomplishments. Imposter phenomenon, more commonly referred to as imposter syndrome, is the feeling of intellectual phoniness that many high-achieving students of color often experience (Peteet et al., 2015, p. 176). Students experiencing Imposter Syndrome believe that they have deceived others about their intellectual abilities and attribute their success to external factors like luck. Imposter Phenomenon hinders the academic achievement of minority students pursuing college degrees and often causes students to disengage from their coursework, attend class less, or even drop out. The constant stress of being found out as a phony or fraud can impact Black students’ well-being and sense of ethnic identity. However, Imposter Syndrome in combination with racial isolation and microaggressions amplifies the struggles of Black students at PWIs.

Lack of Mental Health Resources and Medical Mistrust

The last major cause is the lack of mental health resources at PWIs. At UNC, in particular, there are few resources for students to pursue mental health services. Despite the ongoing mental health crisis on campus, there are very few services on campus to help manage mental health.

Most of the resources are links to mental health hotlines or allow students to reach out to other students, such as Peer2Peer. However, in terms of ongoing mental health care, there is little to no access to therapy (Mental Health and Safety Resources). The primary resource is Counseling and Psychological Services (CAPS), in the Student Health Building. Unfortunately, while CAPS offers individualized therapy sessions, they only last for a maximum of approximately 8 weeks per student.

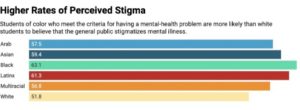

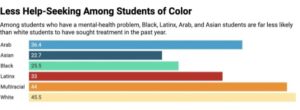

Black students often have more trouble pursuing mental health services (Brown, 2020). This is primarily due to medical mistrust in the Black community that has been deeply ingrained into American history. According to the RAND Corporation, medical mistrust is the “absence of trust that health care providers and organizations genuinely care for patient’s interests, are honest, practice confidentiality, and have the competence to produce the best possible results” (Hostetter and Klein, 2021).

For generations, white biases have harmed Black communities through the medical system. In fact, until the 1965 Civil Rights Act, it was illegal for Black people to receive professional medical care. False perceptions and implicit biases are the main causes of disparities in healthcare. According to studies, 50% of medical students and residents believe that Black and white people are biologically different from one another (Hostetter and Klein, 2021). The culture in medical institutions that makes minorities distrust medical professionals can be influenced by individual mindsets. One of the most infamous examples of medical mistrust was the 1940s Tuskegee Syphilis Study. Without their informed consent, the study observed the symptoms and ailments of 600 Black men, many suffering from Syphilis (Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, 2021).

It is no secret that mental health is considered a controversial topic in America. Mental health, as discussed previously, has a lot of stigma surrounding its effectiveness and necessity. UNC, like many other universities, makes it very difficult to find information surrounding its assets. Regarding the university’s transparency on its goals of providing quality mental health services, UNC fails to make this easy for its students.

According to the Daily Tar Heel, the fiscal budget for CAPS ranges from $3.2 million to $3.5 million. Over 90% of CAPS funding pays for employee salaries (Carroll, 2022). Less than 1% of UNC’s $4 billion budget goes to improving student mental health (DeLuzuriaga, 2021).

As a public university, with a long, complex, and exclusionary history, schools like UNC need to provide information on what changes they plan to make. In the wake of the ongoing mental health crisis that has plagued UNC campus and neighboring schools, student mental health care needs to take priority. Using this data, it is clear that innovation in the field is not a priority for the administration.

Making Policy Changes at PWIs

Caption: UNC’s Black Student Movement Celebrates Black History Month. From: https://www.uncbsm.com/donate

How can college administrators work to improve the mental health of Black students at PWIs? Here are three possible solutions that PWIs could implement to improve the mental health of Black students:

Solution 1) Creating Black spaces on PWI campuses

This solution would fund the construction or addition of a new space dedicated to students of color on campus: designated multi-cultural spaces. A great example of this solution was recently implemented at UVA in the student union. The space was a meeting place for cultural clubs and minority students to gather, study, and connect. One student claimed, “It was almost like our living room … The [Multicultural Student Center] feels like a home away from home” (Kelly, 2020). The student believed the space gave minority students a sense of community within their PWI. The UVA Multicultural Student Center establishes a stronger sense of community and combats the hostile and unwelcoming environment sometimes found at PWIs. Another example is the Morris Family Multicultural Student Center at Kansas State University. In addition to the services offered at UVA, this center provides a strong support system for students of color including support groups, academic resources, and advising. This program would create jobs for more Black and brown advisors and educators and strong connections between students and faculty (Marney, 2019).

The benefits of this solution are abundant. However, limitations could hinder its success. Finding a good location on existing campuses can be difficult, and costly if construction is necessary. One way to save would be to repurpose and remodel an existing space. On UNC’s campus, for example, there are very few locations that could be either converted or receive an addition of this size due to the campus’ age and clustered layout.

However, the need for this sort of space would be monumental for not only Black students but other minority groups as well.

Solution 2) Unconscious Bias Testing

Unconscious bias testing directly addresses one of the primary causes of the mental health gap between non-Black and Black students: microaggressions and discriminatory behavior. Using a Harvard research group’s assessment called the Implicit Association Test (IAT), researchers could measure existing levels of unconscious bias in faculty, staff, and administrators (who make up student support teams) at PWIs (Maina et al., 2018). It is vital for members of the community who directly impact student experiences on campus and in the class to analyze their unconscious biases. As discussed previously, microaggressions from student support teams reduce students of color’s academic performance, increase their risk for depression and anxiety, and decrease their likeliness to reach out for help. Requiring student support teams to attend discussions on race and ethnicity in higher education would ensure that they engaged with unconscious bias recognition and training. Discussions would benefit from state-level diversity and inclusion board, especially in the case of public institutions like UNC.

Where bias training often fails is inconsistent interactions with the material. Following the initial assessment, further testing and discussion are necessary to implement the teachings into everyday life. Implementation of bias training program is possible if organizers use professional development modules that target racial biases in higher education and encourage implicit bias training annually.

While ideal, there are a few limitations that complicate unconscious bias training. It may be difficult to fund an initiative due to the cost of hiring professionals, developing modules, and dedicating university staff to undergo training. Additionally, many institutions believe that they currently hold satisfactory levels of anti-discrimination policy and may be unlikely to undertake further action.

Solution 3) Individualized Therapy

The final solution is expanding individual therapy sessions as a part of student health plans. This program was successful at Brown University, which hired a diverse staff of therapists to allow all students to ask for help. The Flexible-Care Model (FCM) uses 25–30-minute sessions at pop-up locations across campus specializing in mental health care for students of color (Brown, 2020). Many of these are in multicultural student centers as described in solution one. At large institutions such as UCLA where wait times are longer, the RISE Center provides academic support for Black students and helps alleviate stressors from both academic and real life (Rise Center).

Despite most college students experiencing mental health symptoms and high stress levels due to rigorous coursework, students are hesitant to pursue mental health care. Dr. Colleen Conley and her team at the University of Loyola Chicago created a study in which a group of students was evaluated psychologically before entering college and following their first year. Students who engaged with campus mental health services that employed cognitive behavioral therapy and stress management techniques experienced long-term benefits from these interventions (Conley et al., 2013).

Traditionally, colleges follow an individual-based treatment model. However, these services are often underfunded and ineffective. In contrast, the FCM combats many of the costly obstacles that prevent schools from employing individual-level care. Group therapy, while often seen as more effective for college-aged students, does not account for the experiences of minority students. Black students may have different experiences and backgrounds from their white peers which might make group therapy an unviable option.

Another benefit of the FCM is the diverse nature of its staff and practice which would decrease levels of stigma for Black students. A National Bureau of Economic Research study questioned the impacts of Black patients receiving care. Black Americans often benefit from seeking care from Black health care providers.

For example, in the realm of physical health, Black men who received Black male doctors were more likely to seek preventative care, reducing the racial mortality gap by 18% (Torres, 2018). If the FCM is implemented, it could combat the stigma surrounding counseling within the Black community on college campuses and improve the mental health of participating students.

University Multicultural Centers, listed from left to right: Morris Family Multicultural Student Center at Kansas State University, The Multicultural Student Center at the University of Virginia, CGI Rendering of the new MSC at Michigan State University

Recommended Policy Solution for UNC-CH

With these solutions in mind, how can PWIs work to implement change? My recommendation is to combine solutions two and three. While solution one would actively create Black spaces on campus, it is the most costly and complex solution regarding staffing and space. Implementing the IAT on an institutional level through professional development and upgrading campus mental health services would be far less complicated. The primary obstacle is the political complexities associated with holding tenured staff members and the administration accountable for their own racial biases. Ideally, the IAT and FCM will work hand in hand because psychologists and mental health professionals would have to participate in the same unconscious bias training that other faculty and staff would be mandated to partake in. Students of color would receive hands-on care that is long-term and serves their unique to the experiences at PWIs.

Sources

Brown, S. (2020, July 7). Students of Color Are Not OK. Here’s How Colleges Can Support Them. The Chronicle of Higher Education. https://www.chronicle.com/article/students-of-color-are-not-ok-heres-how-colleges-can-support-them

Bullion, M. (2023). MSU Multicultural Center construction to commence this spring. MSU Today. https://msutoday.msu.edu/news/2023/msu-to-begin-construction-on-multicultural-cente r-spring

Carroll, K. (2022, January 25). A look at funding for UNC Counseling and Psychological Services. The Daily Tar Heel. https://www.dailytarheel.com/article/2022/01/university-caps-funding

Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. (2022, December 22). The U.S. Public Health Service Untreated Syphilis Study at Tuskegee. https://www.cdc.gov/tuskegee/timeline.htm.

Clark, I., & Mitchell, D. (2018). Exploring the Relationship Between Campus Climate and Minority Stress in African American College Students. Journal Committed to Social Change on Race and Ethnicity, 4(1)co, 67–95. https://www.jstor.org/stable/48645343

Common Data Sets. (n.d.) North Carolina Agricultural and Technical State University. Retrieved April 4, 2023, https://www.ncat.edu/provost/ospie/analytics/common-data-sets.php

Conley, C. S., Travers, L. V., & Bryant, F. B. (2013). Promoting Psychosocial Adjustment and Stress Management in First-Year College Students: The Benefits of Engagement in a Psychosocial Wellness Seminar. Journal of American College Health, 61(2), 75–86. https://doi.org/10.1080/07448481.2012.754757

Cooper, L. A., Saha, S., & van Ryn, M. (2022). Mandated Implicit Bias Training for Health Professionals: A Step Toward Equity in Health Care. JAMA Health Forum, 3(8). https://doi.org/10.1001/jamahealthforum.2022.3250

DeLuzuriaga, T. (2021, January 28). Understanding Carolina’s budget. The Well. https://thewell.unc.edu/2021/01/28/understanding-carolinas-budget/

Grier-Reed, T., Gagner, N., & Ajayi, A. (2018). (En)countering a White Racial Frame at a Predominantly White Institution: The Case of the African American Student Network. Journal Committed to Social Change on Race and Ethnicity, 4(2), 65–89.

Hostetter, M., & Klein, S. (2021). Understanding and Ameliorating Medical Mistrust Among Black Americans. The Commonwealth Fund. https://doi.org/10.26099/9grt-2b21

Individual Counseling at Counseling and Psychological Services. (n.d.). Brown University. Retrieved April 2, 2023, https://caps.brown.edu/our-services/individual-counseling.

Kelly, J. (2020, February 7). 4 New and Expanded Student Centers Create ‘Inclusive Community of Trust.’ UVA Today. https://news.virginia.edu/content/4-new-and-expanded-student-centers-create-inclusive- community-trust

Lipson, S. K., Zhou, S., Abelson, S., Heinze, J., Jirsa, M., Morigney, J., Patterson, A., Singh, M., & Eisenberg, D. (2022). Trends in Colege Student Mental Health and Help-Seeking by Race/Ethnicity: Findings from the National Healthy Minds Study, 2013–2021. Journal of Affective Disorders, 306, 138–147. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jad.2022.03.038

Lomotey, K. (2010). Predominantly White Institutions. In Encyclopedia of African American Education (pp. 524–526). SAGE Publications, Inc. https://doi.org/10.4135/9781412971966

Marney, J. (2019, March 21). This is what the new multicultural student center could look like, K-State says. The Collegian. https://www.kstatecollegian.com/2019/03/21/this-is-what-the-new-multicultural-student-center-could-look-like-k-state-says/.

Maina, I. W., Belton, T. D., Ginzberg, S., Singh, A., Johnson, T. J. (2018). A Decade of Studying Implicit Racial/Ethical Bias in Healthcare Providers Using the Implicit Association Test. Social Science & Medicine, 199, 219-229. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.05.009.

Mental Health and Safety Resources. (n.d.). Department of Microbiology and Immunology at the University of North Carolina of Chapel Hill. Retrieved March 24, 2023, from https://www.med.unc.edu/microimm/resources/mental-health-and-safety-resources/

Nealy, M. J. (2007). Addressing the Mental Health Ailments Facing Black College Students. https://vb3lk7eb4t.search.serialssolutions.com/?genre=article&atitle=Addressing%20th e%20Mental%20Health%20Ailments%20Facing%20Black%20College%20Students.& title=Diverse%3A%20Issues%20in%20Higher%20Education&issn=15575411&isbn= &volume=24&issue=21&date=20071129&year=2007&au=Nealy%2C%20Michelle%2 0J.&spage=19&sid=EBSCOhost:trh:27690936

Patterson, T. J. (2019). Black mental health matters: An afrocentric analysis of the modern epidemic of black students’ well-being at predominantly white institutions [Undergraduate Honors Thesis, SUNY New Paltz]. https://soar.suny.edu/handle/20.500.12648/1428

Peteet, B. J., Montgomery, L., & Weekes, J. C. (2015). Predictors of Imposter Phenomenon among Talented Ethnic Minority Undergraduate Students. The Journal of Negro Education, 84(2), 175–186. https://doi.org/10.7709/jnegroeducation.84.2.0175

Powell, J. (2021). Impacts of PWI campuses on Black Students Mental Health and Academic Performances. Resilience In Your Student Experience. Honors Capstones 648. [Undergraduate Honors Thesis at SUNY New Paltz]. https://huskiecommons.lib.niu.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1647&context=studentengagement-honorscapstones

Rise Center. University of California Los Angeles. Retrieved April 26, 2023, from https://risecenter.ucla.edu/

Robson, D. (2021, April 25). What unconscious bias training gets wrong… and how to fix it. The Observer. https://www.theguardian.com/science/2021/apr/25/what-unconscious-bias-training-gets-wrong-and-how-to-fix-it

Operating Budget: Fiscal Year 2022-2023. The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. https://finance.unc.edu/wp-content/uploads/sites/298/2023/09/2023-annual-operating-budget-book.pdf

Thyden, N. H., McGuire, C., Slaughter-Acey, J., Widome, R., Warren, J. R., & Osypuk, T. L. (2022). Estimating the Long-Term Causal Effects of Attending Historically Black Colleges or Universities on Depressive Symptoms. American Journal of Epidemiology, kwac199. https://doi.org/10.1093/aje/kwac199

Torres, N. (2018, August 10). Research: Having a Black Doctor Led Black Men to Receive More-Effective Care. Harvard Business Review. https://hbr.org/2018/08/research-having-a-black-doctor-led-black-men-to-receive-more- effective-care.