Listen to the Story: Banksy, Tyler the Creator, and Nihilism in Urban Artistic Expression

Abstract

Art, as an expression of feelings, worldviews, and personal beliefs, is a reflection of our environment and how we interact with it. In this way, urban art such as rap music and graffiti can serve as a lens through which we are able to examine the state of the urban environment. Building on community literature that addresses the presence of nihilism in rap music, this work will establish that nihilism is a prevalent theme in the broader category of urban artistic expression through a content analysis of two artists’ work: Tyler the Creator’s rap music and Banksy’s graffiti art. The current work will then examine these artists’ motives in including nihilism within their art, raising important questions about the current state of the urban environment.

Introduction and Background

Art acts as a collective mirror through which we can more closely examine and learn about our society, our surroundings, and ourselves. As John Lennon once said, “My role in society, or any artist’s or poet’s role, is to try and express what we all feel. Not to tell people how to feel. Not as a preacher, not as a leader, but as a reflection of us all” (Anderson 1). We can learn about an oppressive government from the art of the oppressed,; we can learn about the insane asylum from the art of the patient, and; we can learn about the jail from the art of the inmate. It follows, then, that we can learn about urban environments by examining the art of the urbanite. This paper will look at two models of urban art—Banksy’s graffiti art and Tyler the Creator’s rap music—in order to establish that nihilism is a prevalent theme in urban artistic expression. With this basis, it will then be possible to explore what this theme can tell us about the urban environment.

Charis E. Kubrin’s essay I See Death Around the Corner: Nihilism in Rap Music provides the most relevant and comprehensive examination of nihilism in urban artistic expression within the current literature. In her essay, Kubrin engages in an in-depth analysis of over four hundred rap songs from 1992 to 2000 (Kubrin 433). and Kubrin explores how the nihilistic themes in these rap songs reflect the street code that is ever-present in black youth culture in the urban environment (Kubrin 433). Kubrin focuses her work specifically on gangsta rap, a genre of rap pioneered by gang members describing “life in the ghetto from the perspective of a criminal” (Kubrin 435).[i] This paper will also deal primarily with gangsta rap, although the argument presented here could potentially be applied to other forms of rap music.

In this paper, I will build upon Kubrin’s research in three ways. Although Kubrin directly addresses the presence of nihilism in rap music. However, within her paper and within the scholarly community as a whole, , analyses explicitly connecting nihilism and graffiti are almost nonexistent. It is clear that there is a lack of the scholarly community lacks literature that synthesizes both rap and graffiti as modes of urban art, identifies nihilistic themes within the two, and connects these ideas to the larger context of urban artistic expression. TheMy primary focus of this paper will be to expand Kubrin’s argument by exploring graffiti as another mode of urban artistic expression and arguing that nihilism is a theme throughout various forms of urban art, not just rap music.

Secondarily, this paperI will expand Kubrin’s original thesis by examining the work of Tyler the Creator, a rap artist whose body of work has been created post-2000, and examine whether Kubrin’s original claim still holds true when it comes to contemporary more modern rap music. Originally, Kubrin did not explore post-2000 music because ofdue to the increasing influence of record labels on rap lyrics and the fear that more recent lyrics would focus more on “exaggerated fantasies” than on real issues (Boyd 69; Kubrin 442-443). Through the example of Tyler the Creator, this paper I will propose that although such fantasies may not represent reality on the streets, they are reflective of a larger nihilistic attitude and mindset that is a reality within the urban community and perhaps even beyond.

Finally, Kubrin’s research focuses on rap music as an art form reflective of the African-American urban communityexperience, and therefore it may seem that rap music is more representative of an African-American reality than an urban reality. However, recent shifts in the lyrics and style of rap music suggest that hip-hop is moving away from defining the African-American personawhat it means to be solely African-American, and towards defining the what it means to be an urban citizen. USC School of Cinematic Arts professor and pop culture expert Todd Boyd discusses this recent phenomenon in his book Am I Black Enough for You?, stating that

Audience members of all races use the music as a form of resistance or rebellion, with the truly disadvantaged Black male serving as the supreme representative of adolescent angst, minority disenfranchisement, and an overall sense of cynicism about American society. Thus gangsta rap provides a vehicle for cathartic expression well beyond an exclusively Black space. (64) [ii]

It is important to note that this does not discredit hip-hop as an expression of black culture, stating only just states that it also speaks to a larger, not solely African-American, whole. In this paper, I will focus on this larger whole, evaluating urban artistic expression as a reflection of the urban environment. To begin to focus on this larger whole, it is first necessary to define two terms: nihilism and urban artistic expression.

What is Nihilism?

There are two branches of nihilism:, negative nihilism and reactive nihilism. Negative nihilism refers to the degradation of life through the belief in higher values; in other words, —by believing in the fiction of higher values, we then render the rest of life unreal. There are no higher values, as they are inherently fictional, and thus no life, as the belief in the fictional has rendered reality nonexistent (Deleuze 147). Reactive nihilism is the response to the realization of negative nihilism. Realizing that higher values only depreciate life, the reactive nihilist begins to reject higher values, coming to the conclusion that, to paraphrase Nietzsche, “Nothing is true, nothing is good, God is dead” (Deleuze 148, Goudsblom 30-34). TIn this paper I will focus specifically on reactive nihilism. The three characteristics of nihilism that Kubrin chooses to focus on in her analysis are: “bleak surroundings with little hope, pervasive violence in the ghetto, and preoccupation with death and dying” (444). Based on the literature I consulted, this paper will utilize a broader definition.I chose to broaden this definition. The primary aspect of nihilism as defined in the literature is the rejection of higher values (Deleuze 147-148, Goudsblom 30-34). The other two themes I identified stem from this centralsame idea. Thus, the three characteristics I will focus on are: the rejection of higher values, the devaluation of life and property, and the loss of hope in one’s surroundings.

What is Urban Art?

Within this paper, references when referring to urban artistic expression are, I am referring to art containing that contains the following three characteristics:

1. The artistic form must originate within an urban environment.

2. The artistic form must consistently refer to and draw from its urban roots.

3. The artistic form is not ‘high art’, so to speak, but art of the common urban man.

It is necessary to engage in a deeper discussion of Banksy’s graffiti art and Tyler the Creator’s rap music in order to establish that they are modes of urban artistic expression according to these criteria.

Graffiti and Banksy

In Banksy’s words, graffiti is “…actually one of the more honest art forms available. There is no elitism or hype, it exhibits on the best walls a town has to offer and nobody is put off by the price of admission” (8). Although not originally a strictly urban art form, modern graffiti has grown within city centers, perhaps because the city offers so many natural canvases for graffiti –, from subway walls to bridges and highways. In his essay Art in the Streets, Jeffrey Deitch, director of the Museum of Contemporary Art in Los Angeles, describes graffiti art as being created by teenagers, “emerg[ing] from housing projects, subway yards, and bleak suburban parking lots” (10). According to Deitch, graffiti art exploded in the 1970s within urban centers, becoming more mainstream in the 1980s with artists bringing graffiti art into the galleries and giving it “artistic credibility” (10-11). Graffiti art also permeated mainstream culture through other publicly accessible mediums such as music videos andor popular films.[iii] Interestingly, Deitch also describes graffiti art as paralleling the hip-hop movement, the “artistic vocabulary [of graffiti] spilling over into break dancing, street fashion, and the language and rhythms of rap music” (10). Largely due to the increased enforcement of anti-graffiti laws, street art stagnated during the late 80s and early 90s, rejuvenating in later years with the work of artists such as COST, REVS, Barry McGee, Shepard Fairey, and, of course, the Bristol-based anonymous street artist commonly referred to as Banksy (Deitch 13-14).

In Banksy’s words, graffiti is “…actually one of the more honest art forms available. There is no elitism or hype, it exhibits on the best walls a town has to offer and nobody is put off by the price of admission” (8). Every work of graffiti also inherently refers back to the city, as the wall or sign it is painted on is both part of the city and part of the art. It is almost unnecessary to point out that Ggraffiti is by nature accessible to the common urban man; as it is usually illegal, it is generally not promoted as a form of sophisticated art. Additionally, the materials that graffiti requires are easily accessible, —as Banksy points out in his Advice on painting with stencils: “A regular 400mL can of paint will give you up to 40 A4 sized stencils. This means you can become incredibly famous/unpopular in a small town virtually overnight for approximately ten pounds” (237). Along these same lines, graffiti is a unique art form in the sense that it is ever changing. In a way similar; similarly to Internet forums and sites like Wikipedia, graffiti is constantly being edited. As pointed out by John Hudson in his essay Banksy: The story so far…, even Banksy’s work sometimes falls “victim to fellow graffiti artists” (23). This speaks to the honesty of graffiti—as it is constantly being edited, the current popular opinion is always on top.

This current opinion is especially influential for popular graffiti artists such as Banksy, whose work, distributed via the Internet and other such venues, permeates contemporary culture beyond just the streets in distribution via the Internet and other such venues. I chose to focus specifically on Banksy’s art largely because his enormous popular appeal emphasizes the cultural relevance and influence of graffiti art outside of the city center. This popularity serves as a venue for widespread knowledge of the issues in urban environments and the potential for change. Some, like Hudson, question how Banksy is still able to truly represent the common urban man when he displays his pieces in galleries and sells them for millions to celebrities like Angelina Jolie. However, in the words of Paul Gough in his essay Banksy: The Urban Calligrapher, “Banksy may have entered the mainstream, stepping out of the shadows of urban Britain into the glitz of Hollywood, but…he still has an unerring ability to pass penetrating comment on the hot issues of the day” (145). Regardless, in order to prevent inaccuracies, in this paper I will focus specifically on Banksy’s graffiti art, not his gallery work.

Rap and Tyler the Creator

Paul Gilroy, Professor at the London School of Economics and author of a chronicle of African cultural history entitled The Black Atlantic: Modernity and Double Consciousness, describes rap music as “a hybrid form nurtured by the social relations of the South Bronx where Jamaican sound system culture was transplanted during the 1970s and put down new roots” (qtd. Calvente 51-52). Hip hop as we know it today grew from these urban roots, and although there are rap artists who did not grow up in an urban setting, rap music still continuously references and draws from its originsthese urban roots.

As American philosophy professor Crispin Sartwell points out in his essay Rap Music and the Uses of Stereotype, this reference to urban surroundings is made apparent in “the rapper’s claim to be ‘representing’…some constituency” (375). In this way, “rRap refers its authority to represent to the hood, gang, or crew, and makes an issue of whether the rapper has stayed true to that constituency or turned her back on them” (Sartwell 375). The realness and authority of a rap artist amongst the urban constituency isare dependent upon the rapper’s ability to represent the urban reality (Sartwell 375). Additionally, the medium of rap music, like that of graffiti, is easily accessible to the masses. The spoken word is free, and the need for a well-known label to gain popularity is quickly diminishing; artists like Tyler the Creator and his collective Odd Future spread their music and found notoriety through the internet, releasing EPs, posting videos, and blogging online (Conner). This technology-based growth is analogous to the spread of graffiti through music videos and popular films in the 1980s. Due to Because of this, rap music can be classified as urban art: it originated in the urban environment of the South Bronx, it consistently represents these roots, and to this day, rap music is still art of the common urban man, often starting on the streets and later gaining widespread popular appeal.

One such artist who has recently received enormous popular acclaim is 19 year old Tyler the Creator and his brainchild rap collective, Odd Future (short for OFWGKTA, or Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All). British newspaper The Guardian describes Odd Future as “giddily nihilistic”, ArtInfo dubs them “L.A.’s Hottest Nihilistic Art Rap Collective”, The Spin calls him “Americas favorite young Nihilist” (Hoby; Binlot; Martins). Tyler the Creator is a 19 year old up-and-coming artist and internet sensation exploding onto the current music scene with his brainchild rap collective, Odd Future (short for OFWGKTA, or Odd Future Wolf Gang Kill Them All). The nihilistic themes in Tyler’shis art are serving as what The New York Times calls: “the flashpoint for reigniting the culture wars in hip-hop” (Caramanica). In addition to his recent popularity, there are several other reasons this paperI chose to focuses on Tyler as an artist. First, although there are a multitude of music reviews and blogs that discuss his work, as of yet there are very few scholarly publications that analyze his music. FirstSecond, Tyler’s African-American cultural background contrasts with Banksy’s white British one, indicating that the commonality between their works, nihilism, stems from the urban roots of their art, not from other factors such as race or nationality. SecondFinally, it is important to note that Tyler, unlike earlier gangsta rap artists such as The Notorious B.I.G. or Nas, grew up in the suburbs; he was born and raised in Ladera Heights, just outside of Los Angeles (Caramanica). Although Tyler did not grow up in the inner city, he still creates his music in the style of gangsta rap, and he serves as a strong example of how art with roots in the city does not necessarily have to be created in the city to serve as a reflection of the urban environment.

Now that we have established a working definition of urban artistic expression and identified two artists to focus on within this genre, we can examine the work of these two artists in order to identify the characteristics of nihilism within their work.

A. The Rejection of Higher Values

1. Banksy

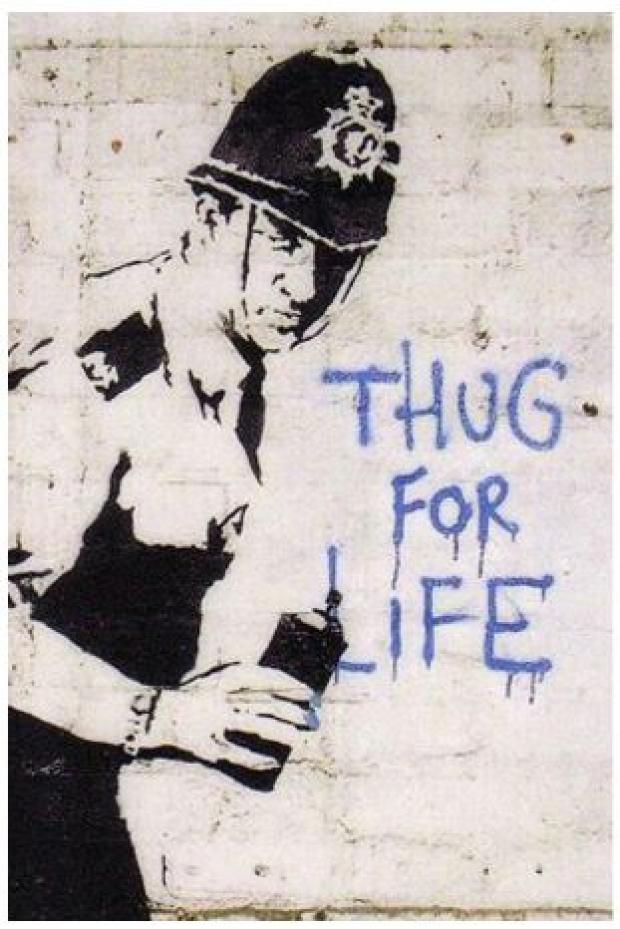

The first characteristic of nihilism, the rejection of higher values, is seen primarily through two themes in Banksy’s art: the rejection of law and the rejection of religion. The rejection of the the law can be seen in Banksy’s many paintings depicting policemen in compromising or degrading positions (i.e. next to profanity, peeing on a wall, or breaking the law) (see Appendix A, Figures 1, 2, 3, 4). Placing figures of authority in such situations diminishes their power and transformsurns the law into a laughable matter. Along the same lines, a number of Banksy’s images promote anarchy and disorder through direct statements or symbols. For instance, in Figure 5, Banksy tags a monument with the phrase “Designated Riot Area”, and in Figure 6, a British soldier paints the anarchy symbol on a wall, openly rejecting the very institution of which he is purportedly a member of (see Appendix A, Figures 5, 6).

The rejection of religious values is seen in Banksy’s Banksy use ofs traditional religious figures such as angels in order to reject higher religious values. This is seen in Figure 7 and Figure 8, both of which show angels in unusual states. In Figure 7, a dejected and downtrodden male angelic figure is pictured with a bottle of alcohol and a cigarette (see Appendix A, Figure 7). This reflects a distinct loss of faith in the higher state of being that is traditionally represented by angels. Similarly, in Figure 8, a female angel is shown with a gun hovering amidst her halo (see Appendix A, Figure 8). This contradictory imagery depicts the traditionally peaceful figure blindly worshiping a symbol of violence, implying hypocrisy turning her into a hypocrite and diminishing the angel’sher traditional role as a guardian.

2. Tyler the Creator

Tyler the Creator also demonstrates the rejection of higher values through the rejection of religion and social institutions. Lyrics such as “Jesus called, he said he’s sick of the disses/I told him to quit bitching/this isn’t a fucking hotline for a fucking shrink” or “My only problem is death/Fuck heaven, I ain’t showing no religion respect” degrade traditional religious figures and dismiss the idea of religion (Tyler the Creator, “Yonkers; “Nightmare”). Tyler is a self-proclaimed atheist and the rejection of religion is a theme throughout his music.

Odd Future’s music contains many lyrics that echo Nietzsche’s sentiment “Nothing is true, nothing is good, God is dead” (Deleuze 148). Lines such as “Kill people, burn shit, fuck school/Odd Future here to steer you to what the fuck’s cool/ Fuck rules, skate life, rape, write, repeat twice” demonstrate Tyler’s headfirst dive into negative nihilism, depreciating social institutions and higher values with a vehemence so strong that his lyrics are often interpreted as being ironic (Odd Future, “Pigions”).[iv]

B. The Devaluation of Life and Property

1. Banksy

The devaluation of life and property is seen through various themes in Banksy’s work, including property abuse and Banksy’s use of rats as symbols of the urban citizen. Graffiti is inherently a devaluation of property ownership; in order to create graffiti in the traditional, illegal sense, one has to devalue the authority of the law and the concept of property ownership to some degree. Renowned New York art critic Carlo McCormick reinforces this point in his essay The Writing on the Wall, describing graffiti art as “inherently anti-institutional” (McCormick 19). An overt example of this devaluation of property is seen in Figure 9, which is an image of a Banksy stencil reading “Designated Graffiti Area” (see Appendix A, Figure 9). Figure 10 depicts the before and after—the originally blank wall with Banksy’s tag contrasted with a more colorful version several weeks later (see Appendix A, Figures 9, 10). This piece, having been duplicated in many cities around the world, undermines the traditional view of property as belonging to and being controlled by one entity and instead opens it up as a public art space.

In addition to a disregard for property rights, Additionally, Banksy’s art often features violent imagery, as seen in the previously mentioned depiction of the angel with a gun over her head (see Appendix A, Figure 8). Banksy also has a series of photos that juxtapose famous figures, (such as the Mona Lisa,) with violent imagery (see Appendix A, Figure 11). This contraposition reflects a devaluation of life by icons representative of society.

Finally, a great deal of Banksy’s work centers on images of rats. Banksy describes his use of rats in his book Wall and Piece, saying that, “They exist without permission. They are hated, hunted and persecuted. They live in quiet desperation amongst the filth. And yet they are capable of bringing entire civilizations to their knees. If you are dirty, insignificant and unloved then rats are the ultimate role model” (95). In this sense, the rat serves as a symbol for the underprivileged urban citizen. Banksy often portrays the rats breaking laws, being mischievous, or with negative attitudes, and this reflects the devaluation of the urban citizen to the form of a rebellious street animal (see Appendix A, Figures 12, 13, 14).

2. Tyler the Creator

The devaluation of life and property is also seen in the works of Tyler the Creator and Odd Future, primarily through violent imagery and the degradation of women. This is demonstrated through lyrics such as “While you niggas stacking bread, I can stack a couple dead/ Bodies, making red look less of a color, more of a hobby” or “Honey on that topping when I stuff you in my system/Rape a pregnant bitch and tell my friends I had a threesome” (Tyler the Creator, “Tron Cat”). These are some of Tyler’s most controversial lyrics, and imagery similar to this is seen throughout his body of work.[v]

C. A Lloss of Hhope in Oone’s Ssurroundings

1. Banksy

In Banksy’s work, the loss of hope in one’s surroundings is shown primarily through the juxtaposition of happy images with violent or tragic imagery. Often, he contrasts youthful figures—symbols of hope, innocence, and happiness—with weaponry (see Appendix A, Figures 15, 16) or tragic circumstances such as (the wall dividing Israel and Palestine or a derelict car factory, (see Appendix A, Figures 17, 18). A similar juxtaposition of images is seen in Figures 19 and 20, with happy images such as gifts or picnics contrasted with violence, filth, and poverty (see Appendix A, Figures 19, 20). These contrasting images suggest that negative aspects of society have corrupted traditional symbols of hope.

2. Tyler the Creator

In addition, a number of Tyler’s songs feature him talking to a therapist (both of his albums, Bastard and Goblin, center around this theme), and he frequently entertains suicidal thoughts. These thoughts echo his loss of hope in life. One example of this is found in Tyler’s song Bastard, when he states, “I know you fucking feel me, I want to fucking kill me” (Tyler the Creator, “Bastard”). Similarly, in Yonkers, Tyler speaks of the suicide of first his conscience and then himself: “(Fuck everything, man) That’s what my conscience said/ Then it bunny hopped off my shoulder, now my conscience dead/ Now the only guidance that I had is splattered on cement / Actions speak louder thant words, let me try this shit, dead” (Tyler the Creator, “Yonkers”)[vi].

Purpose

Having established that nihilism is a prevalent theme in urban artistic expression, the question is: why? Why do these artists choose to include nihilistic themes within their work and do these motivations change from artist to artist?

Although the images previously analyzed certainly reflect nihilistic themes, a sector of Banksy’s artwork reflects a more revolutionary and hopeful strain of thought. For example, the Banksy painting shown in Figure 21 features an ape, which, like the rat discussed earlier, is representative of the impoverished and oppressed urban citizens, juxtaposed with the statement “Laugh now but one day we will be in charge” (see Appendix A, Figure 21). This is an image of hope, a call for future change. In this image lies the meaning and purpose of Banksy’s work: to highlight the issues with the current urban environment, and then to take this one step further and ignite a change. Thus, although nihilism is prevalent throughout Banksy’s artwork, it is present because it is a reflection of the urban environment. Banksy, then, is not a nihilist—just an artist using nihilistic themes to highlight an issue and inspire a change.

Tyler the Creator, on the other hand, is a bundle of contradictions. He puts it beautifully in his song Yonkers: “I’m a fucking walking paradox, no I’m not” (Yonkers). Within his music, Tyler recognizes his inconsistencies, creating various different personas for himself, including Tron Cat and Wolf Hayley, both bad-influence personas, Dr. TC, his conscience and therapist, and Ace Creator, Tyler’s more emotional and personal side. As he says in his song Nightmare, “One ear I got kids screaming, ‘O.F. is the best’/The other ear I got Tron Cat, asking where the bullets and the bombs at/So I can kill these levels of stress, shit” (Tyler the Creator, “Nightmare”). This shows the contrast between the different sides of his multi-faceted personality.

Some propose that Tyler’s music is satirical—an ironic representation of hip-hop culture, poking fun at the nihilistic themes typically found in rap music by taking them to the extreme. They excuse his violent imagery with the fact that it is just that—imagery; he never lives out any of the fantasies he envisions. This is perhaps an interesting testament to the fact that Tyler is a gangsta rap artist living in suburbia; unlike artists such as Tupac or The Notorious B.I.G, he fantasizes about violence and death without actually living it. Another interesting point to consider in relation to this aspect of Tyler is the concept that these fantasies are not just his own; —the popularity of his music indicates that they are fantasies shared or at least enjoyed by a larger part of the population. In his biography, Decoded, rap artist Jay-Z discusses how businessmen often listen to his music as motivation before important presentations, and the point he makes through this is summarized nicely by Zach Baron in his article On Odd Future, Rape and Murder and Why We Sometimes Like Things That Repel Us: “…with art like this you never identify with the victim, the proverbial ‘you’; you identify with the person speaking, and that person is a bad motherfucker, and thus so is the listener. Through this type of identification, art allows us to explore the weird frisson between reality and fantasy, the gulf between who we are and who we’d like to be” (Baron).

In this sense, the issues that are being raised by Banksy and Tyler the Creator are issues that don’t necessarily apply to just the state of the urban environment; they may speak to a larger question of the state of mind of the modern population—why do we idealize the nihilistic imagery in urban artrap music? Why is it something we look up to and want to identify with? And what does this mean about us?

Others assert that Tyler is simply nihilistic and misogynistic, spouting lyrics about violent rape fantasies, and yet another interpretation is that Tyler is just a screwed up teenage boy, messing around with his friends and making songs without really thinking about their consequences. Seemingly supporting the latter, Tyler explained his graphic lyrics iIn an interview with The Chicago Sun Times, Tyler explained his graphic lyrics by saying “Sometimes it’s us seeing who comes up with the sickest shit, the most disgusting thing they can throw in” (Conner).

I would argue that the real Tyler is a combination of the three—a creative teenage boy messing around with his friends, at times poking fun at everyone and everything around him, at other times completely serious. One can never really tell the difference between the latter two—it is difficult to decipher when Tyler is actually confessing the thoughts that go on inside his messed-up head or when he is just trying to mess with our heads. Is he, like Banksy, trying to prove a point through the nihilism in his music? Or is he just blowing off steam; making the music for the “nigga that’s in the mirror rapping”, as he asserts in his song Goblin (Tyler the Creator, “Goblin”)? Again, I would argue that it is most likely a combination of the two.

Regardless of whether “America’s favorite young nihilist” is actually a nihilist or if he, like Banksy, is trying to prove a point through his work, his music still contains nihilistic themes (Martins). Russell Simmons, co-founder of Def Jam, responded to a 1990 Newsweek article decrying the graphic themes in rap music by saying, “Surely the moral outrage in this piece would be better applied to contemporary American crises in health care, education, joblessness” (Hoby). But what if Newsweek’s graphic themes and Simmons’s American crises are one and the same? Jeffrey Deitch points out that although most artistic movements occur during times of prosperity, both hip-hop and graffiti exploded in the 1970s during a time of economic hardship caused by the Vietnam war, a decline in the stock market, and the 1973 oil embargo (10). Graffiti and rap music exploded as a direct result of these hardships, and they served as both as a form of artistic release and a way to voice dissent. Tyler’s music and Banksy’s graffiti art are modern examples of this same concept. If Tyler’s music and Banksy’s graffiti are indeed reflections of their surroundings, then for urban artists like them, these themes are mirror images of larger societal issues. The devaluation of life and property, the loss of hope in one’s surroundings, the rejection of higher values—these are just the details hovering in the reflection behind the artist “that’s in the mirror rapping” (Tyler the Creator, “Goblin”).

In a world where we often avoid casting our eyes on the more difficult aspects of life, the popularity of urban artists such as Banksy and Tyler the Creator force societys us to look more closely at these details. Theirse images and lyrics alone may not be enough to prove that nihilism is prevalent in urban life, but they do demonstrate that nihilism is prevalent in urban artistic expression. Whether purposefully included in an effort to combat nihilism, or simply present because the artist himself is a nihilist, this themeit forces us to ask important questions: If art is a reflection of our surroundings, then what does this nihilistic presence say about our cities? What does it say about our society as a whole? And, most importantly, is this an attitude that we should overlook as a byproduct of city life, or do we need to more closely examine the policies and social constructs that are at the root of such hopelessness and despair? These are questions with complicated answers, but having established that nihilism is a prevalent theme in urban artistic expression is the first step towards finding a solution. In Tyler’s words, “Its fucking art, listen to the fucking story” (Hoby).

[i] c.f. Kubrin pgs. 434-439 for more information on gangsta rap, its origins, and how it serves as a reflection of the urban community.

[ii] Kubrin, like Boyd, acknowledges that rap artists today have shifted from discussing the general black experience to more specifically addressing the experience of lower-class black urban citizens; I hope to broaden this definition to the experience of lower-class urban citizens (Kubrin 435).

[iii] c.f. Deitch pages 11-12 for more information on the growth of graffiti art through music videos and films.

[iv] See Appendix B: Rejection of Higher Values for additional lyrics of this nature.

[v] See Appendix B: Devaluation of Life and Property for additional lyrics of this nature.

[vi] See Appendix B: Loss of Hope in One’s Surroundings for additional lyrics of this nature.

Appendix A: Banksy Images

For more details about Tyler the Creator’s lyrics, conduct online research.

Sources

1. Books

Anderson, Jennifer Joline. John Lennon: legendary musician & Beatle. Edina, Minn.: ABDO Pub. Co., 2010. Print.

Banksy. Wall and Piece. [New] ed. London: Century, 2006. Print.

Boyd, Todd. Am I Black Enough for You? : Popular Culture from the ’Hood and Beyond. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1997. Print.

Calvente, Lisa. “The Black Atlantic revisited : nihilism, matrices of struggle, and hip hop culture.” MA Thesis. University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, 2002. Print.

Deitch, Jeffrey. “Art in the Streets”. Art in the Streets. Ed. Brooklyn Museum. New York: MOCA, 2011. [10-15].

Deleuze, Gilles. Nietzsche and Philosophy. New York: Columbia University Press, 2006. Print.

Ellsworth-Jones, Will. Banksy : the Man Behind the Wall. London: Aurum, 2012. Print.

Goudsblom, Johan. Nihilism and culture. Totowa, N.J.: Rowman and Littlefield, 1980. Print.

Gough, Paul. “Banksy: The Urban Calligrapher…”. Banksy: the Bristol legacy. Ed. Paul Gough. Bristol: Redcliffe Press Ltd., 2012. [138-145].

Hudson, John. “Banksy: The Story So Far…”. Banksy: the Bristol legacy. Ed. Paul Gough. Bristol: Redcliffe Press Ltd., 2012. [21-25].

McCormick, Carlo. “The Writing on the Wall”. Art in the Streets. Ed. Brooklyn Museum. New York: MOCA, 2011. [19-24].

Sartwell, Crispin. “Rap Music and the Uses of Stereotype”. Reflections : An Anthology of African American Philosophy. Ed. Hardy, William H. Australia; Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 2000. [373-380].

2. Discography Songs

Odd Future. Pigions. Odd Future Records, 2010. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. AssMilk. Odd Future Records, 2009. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Bastard. Odd Future Records, 2009. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Bitch Suck Dick. XL, 2011. MP3

Tyler the Creator. Blow. Odd Future Records, 2009. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Fish. XL, 2011. MP3

Tyler the Creator. French. Odd Future Records, 2009. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Goblin. XL, 2011. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Golden. XL, 2011. MP3

Tyler the Creator. Inglorious. Odd Future Records, 2009. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Nightmare. XL, 2011. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Parade. Odd Future Records, 2009. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Pigs Fly. Odd Future Records, 2009. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Radicals. XL, 2011. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Sandwitches. XL, 2011. MP3

Tyler the Creator. Sarah. Odd Future Records, 2009. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Session. Odd Future Records, 2009. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Seven. Odd Future Records, 2009. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. She. XL, 2011. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Transylvania. XL, 2011. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Tron Cat. XL, 2011. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. VCR. Odd Future Records, 2009. MP3.

Tyler the Creator. Window. XL, 2011. MP3

Tyler the Creator. Yonkers. XL, 2011. MP3.

3. Articles

Baron, Zach. “On Odd Future, Rape and Murder, And Why We Sometimes Like the Things That Repel Us.” The Village Voice. N.p., 10 Nov. 2010. Web. 27 Nov. 2012. .

Binlot, Ann. “Odd Future, L.A.’s Hottest Nihilistic Art Rap Collective, Will Turn Their Tumblr Into a Photography Book.” ArtInfo [New York] 10 Aug. 2011: n. pag. ArtInfo. Web. 28 Aug. 2012.

Caramanica, Jon . “Angry Rhymes, Dirty Mouth, Goofy Kid.” The New York Times [New York City] 4 May 2011, New York ed., sec. Music: AR1. The New York Times. Web. 26 Nov. 2012.

Conner, Thomas. “To Odd Future rapper, thinks it’s funny that rape, murder lyrics anger people.” Chicago Sun-Times 12 July 2011, sec. Entertainment: n. pag. Chicago Sun-Times. Web. 27 Nov. 2012.

Kubrin, Charis E. “I See Death Around the Corner: Nihilism in Rap Music.” Sociological Perspectives 8.4 (2005): 433-459. JSTOR. Web. 28 Aug. 2012.

Martins, Chris. “Tyler, The Creator, ‘Goblin’.” Spin [New York City] 10 May 2011, sec. Reviews: n. pag. Spin. Web. 27 Nov. 2012.