Maternal Mortality Rates in Appalachia

Maternal-fetal medicine manages the prevention and treatment of health issues concerning the mother and the child before, during, and after pregnancy. Maternal health is essential in identifying and targeting health risks in women and preventing problems for both the mother and the child. Identifying risks and understanding the current health conditions of women of childbearing potential can help identify ways to prevent future health issues, improve conditions for mothers and their children, and reduce rates of disease and death, particularly those associated with pregnancy and early childcare. One region where maternal health is lacking and improvements could provide a positive impact is the Appalachian region of the United States, where mother and child health presents a growing healthcare challenge.

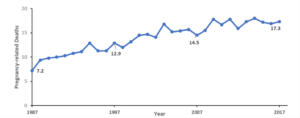

Over the past few decades, pregnancy-related deaths, also known as maternal mortality rates, have been on the rise in the United States from 12.9 deaths per 100,000 live births in 1997 to 17.3 deaths per 100,000 live births in 2017 and have continued to increase in recent years according to the CDC (Figure 1). Rural areas, specifically the Appalachian region, have consistently had higher maternal and infant mortality rates than the national average. This trend of higher maternal mortality rates in Appalachia is due to differences in health and access to healthcare for the populations in these areas or, more generally, spatial variation.

Figure 1. Pregnancy-related mortality ratio per 100,000 live births in the United States.

Data available from https://www.cdc.gov/reproductivehealth/maternal-mortality/pregnancy-mortality-surveillance-system.htm

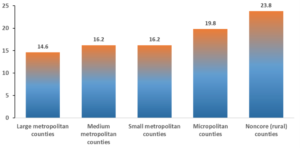

One report published in 2020 by Dr. Mairead Moloney identified risk factors impacting rural Appalachian women for pregnancy-related death and severe maternal morbidity. She compared rural pregnancy-related deaths to urban pregnancy-related deaths using 2016 CDC data. She found that rural areas have higher rates of pregnancy-related death compared to all other regions, which proves significant when compared to large central metropolitan areas, large fringe metropolitan areas, and overall national rates.

Figure 2. Pregnancy-Related Mortality Rates by Urban-Rural Classification (2011-2016). Pregnancy-related mortality rates for rural areas per 100,000 live births was 23.8 deaths for rural areas, compared to 14.6 deaths for metropolitan counties.

Recent studies have cited the underlying health of women as a cause for rising maternal morbidity. Morbidities are any disease or medical condition that increases pregnancy complications, including mortality. The “traditional” causes of pregnancy complications and pregnancy-related deaths – including conditions like pre-eclampsia (seen in pregnant women as dangerously high blood pressure and protein in their urine, as well as swelling of hands and feet), sepsis (the body’s potentially dangerous and extreme response to an infection), and hemorrhage (bleeding) – have declined over the years. Still, new causes of death from pre-existing conditions are increasing rapidly.1These include illnesses like diabetes, hypertension, and heart, renal, and liver disease, which disproportionately affect rural women, according to Dr. Moloney. For background information on the effects of these pre-existing conditions, Dr. Moloney states that,

A woman’s odds of dying from pregnancy-related causes or experiencing life-threatening end-organ damage is 5.87 times greater when experiencing pre-pregnancy hypertension, 6.56 times greater when experiencing chronic renal disease, 5.48 times greater when experiencing chronic ischemic heart disease, and 1.18 times greater when diagnosed with diabetes mellitus.2

This data accounts for all women in the U.S. If any woman experiences these illnesses during pregnancy, her odds of morbidity or even death increase significantly.

Appalachian women aged 18-44 years old, which is considered of childbearing age, have worse self-reported health prior to conception and higher rates of smoking, obesity, and poor nutrition. These women also report lower rates of health insurance and annual check-ups with health care providers. These all predispose Appalachian women to higher chances of pre-existing health conditions that could impact pregnancy outcomes. The Appalachian Regional Commission (ARC) designates the health of women prior to conception as particularly poor in Central Appalachia, which includes Eastern Kentucky and West Virginia. “Nationally, 12.4% of adult women of childbearing age have been diagnosed with hypertension, compared to 20.0% in Kentucky.

Similarly, 5.1% of women of childbearing age nationally have been diagnosed with diabetes mellitus, compared to 8.1% in Kentucky.”3 Roughly 30% of women aged 18–44 years old in Kentucky (29.1%) and West Virginia (30.9%) smoke, compared to 17.1% nationally. Illicit drug use increases pregnancy-related death by 3.26 times, and Kentucky and West Virginia have drug overdose rates of 33.5 and 52.0 per 100,000 individuals, respectively, compared to 19.8 per 100,000 nationally, indicating that pregnant women in rural Appalachia may be at extreme risk for associated complications.4

One comprehensive report, “Health Disparities in Appalachia, ” a collaboration between the ARC and the Sheps Center for Health Services Research here at UNC, corroborated this information. They found that the pre-existing health conditions that increase maternal mortality (e.g., hypertension, diabetes) have higher percentages in the Appalachian Region . For example, the heart disease mortality rate is 17% higher in the Appalachian Region compared to the national rate. In terms of population size, heart disease mortality rates for the Appalachian Region’s rural counties are 27% higher than the rate for the Appalachian Region’s large metro counties.5 For the other pre-existing conditions, this report found that not only were the Appalachian regions higher in percentages than the national rates, but the less populated areas of the Appalachian Region had higher percentages than the higher populated counties of those same regions. The data show an overwhelming agreement that rural women, including women in Eastern Kentucky and West Virginia, have poorer health and higher maternal mortality rates.

Dr. Katy Kozhimannil used the American Hospital Association Annual Survey data to associate loss of obstetric hospital services and pregnancy outcomes. She found that pregnant rural women have diminished access to resources like contraceptive services and obstetric care, which decrease the risk of maternal mortality and morbidity. Between the years 2004 and 2014, 179 rural counties lost hospital-based obstetric services.6 Living in rural areas can complicate access to advanced obstetric and postnatal care, which increases the risk of severe maternal mortality. There is a notable correlation between living in rural areas and maternal morbidities like eclampsia, embolisms, and uterine ruptures. There is less access to prenatal care for rural, Appalachian women compared to women living in micro- or metropolitan cities. These women also start prenatal care at later stages in their pregnancy, increasing their risk of maternal morbidity or mortality.7 Not only do Appalachian women have higher rates of the diseases mentioned before, like diabetes and heart disease, but also higher rates of traditional pregnancy complications. These are correlated with a decrease in both primary and specialty physicians.

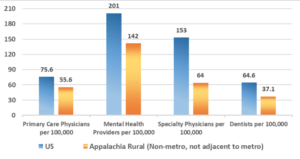

The accessibility of specialty physicians, like obstetricians or maternal-fetal specialists, is 65% lower in Central Appalachia (Eastern Kentucky and West Virginia) compared to the country as a whole.8 Rural Appalachia has lower rates per capita of primary care physicians, mental health providers, and specialty physicians (like maternal-fetal specialists) (See Figure 3).9 The presence of a practicing obstetrician within the county reduces the risk of delivery complications, and the density of maternal-fetal medicine specialists is inversely related to a region’s rate of maternal mortality. Additionally, many rural communities are facing a decline in hospital-based obstetric services. The closure of hospitals is associated with an exacerbation of maternal health disparities in rural areas, including decreased utilization of prenatal care, increased out-of-hospital births, and increased births in hospitals without obstetric units.10

Figure 3. Healthcare Providers. There is less access to healthcare providers in rural Appalachia compared to the broader United States (US).

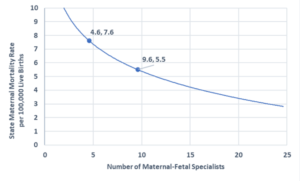

Another article published in the American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology also found maternal-fetal medicine specialist density is inversely associated with maternal mortality ratios. The study showed that an increase of 5 maternal-fetal specialists per 10,000 live births results in a 27% reduction in the risk of maternal death (relative risk [RR] = 0.73, 95% CI = 0.58-0.93, P = 0.012).11 Even after controlling for state-level measures of maternal poverty, education, race, and age, the density of maternal-fetal medicine specialists is inversely correlated with maternal mortality ratios.

Figure 4. State Maternal Mortality Rate. Sullivan and colleagues examined the density of maternal-fetal medicine specialists and corroborated the inverse association with maternal mortality ratios.

Taking a closer look at one state in particular, Kentucky published its Maternal Mortality Review Annual Report in 2020. In Kentucky, the rate of maternal deaths fluctuated from 2013 to 2018. Overall, this number increased from 80.8 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2013 to 140.9 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births in 2018. As stated in Dr. Moloney’s review, drug use is one rising cause of pregnancy-related deaths. In Kentucky, the percentage of accidental maternal deaths due to drug overdose have been around 50% from 2013 through 2018, which accounts for approximately 19% of all maternal deaths in the state. The Kentucky Department of Public Health cites risk factors impacting maternal mortality, including tobacco and drug use, obesity, transportation, access to care, domestic violence, and living in a rural state. They also state that morbidities like diabetes, hypertension, and other health conditions require additional follow-up and management during pregnancy.12 These risk factors are higher in Appalachian regions and are associated with decreased access to health care providers, especially obstetricians. These obstetricians become scarcer as the overall population and access to general practitioners decrease, negatively impacting the health of women with pre-existing conditions.

Numerous studies have shown that better access to primary care is a function of increased numbers of available primary physicians. Not surprisingly, this is associated with better health outcomes,13 health services being used more efficiently and when needed,14 and fewer delays, particularly for more severe conditions.15 However, training new doctors in rural areas has been a difficult challenge. For example, the University of Kansas School of Medicine opened a site in Salina to produce more rural doctors. Of the eight doctors of the first graduating class, only three chose to stay in rural communities with higher needs, and the five other graduating doctors went to cities of varying sizes.16 Attempts to produce more rural doctors have not been as effective as hoped, which may be due to the very high costs of medical school. Understanding why these efforts have been ineffective will be critical to developing new healthcare policy for this underserved region.

It is crucial that we encourage Appalachian residents, particularly women of childbearing potential, to visit and take their children to visits with healthcare providers regularly. Helping educate patients to improve health literacy is just one spoke in the wheel, as access to healthcare is a significant need for this population. More effort must be made to incentivize doctors to practice in more rural communities. As Appalachia’s physician population increases, there are fewer primary care and specialty physicians to replace them. Solutions to provide more access to healthcare are needed, helping patients get the regular care they need and creating and recruiting healthcare workers to provide quality care where it is needed. The economic situation in Appalachia may require creative solutions to address these challenges and provide more care.

Sources

1. Hansen, A., & Moloney, M. (2020). Pregnancy-related mortality and severe maternal morbidity in rural Appalachia: Established risks and the need to know more. The Journal of Rural Health: Official Journal of the American Rural Health Association and the National Rural Health Care Association, 36(1), 3–8. https://doi.org/10.1111/jrh.12383

2. See note above.

3. See note above.

4. Marshall, J. L., Thomas, L., Lane, N. M., Holmes, G. M., Arcury, T. A., Randolph, R., & Ivey, K. (2017). Health disparities in Appalachia. Appalachian Regional Commission. https://www.arc.gov/wp-content/uploads/2020/06/Health_Disparities_in_Appalachia_August_2017.pdf.

5. See note above.

6. Kozhimannil K.B., Hung P., Henning-Smith C., Casey M.M., & Prasad S. (2018). Association between loss of hospital-based obstetric services and birth outcomes in rural counties in the United States. JAMA 319(12):1239-1247. https://jamanetwork.com/journals/jama/fullarticle/2674780.

7. Hansen, A., & Moloney, M. “Pregnancy-related mortality and severe maternal morbidity.”

8. Marshall et al. “Health disparities in Appalachia.”

9. ACOG Committee Opinion No. 586: Health disparities in rural women. (2014). Obstetrics and gynecology, 123(2 Pt 1), 384–388. https://doi.org/10.1097/01.AOG.0000443278.06393.d6.

10. Kozhimannil et al. “Association between loss of hospital-based obstetric services and birth outcomes.”

11. Sullivan, S. A., Hill, E. G., Newman, R. B., & Menard, M. K. (2005). Maternal-fetal medicine specialist density is inversely associated with maternal mortality ratios. American Journal of Obstetrics and Gynecology, 193(3 Pt 2), 1083–1088. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ajog.2005.05.085

12. Kentucky Department of Public Health (2020). Maternal Mortality Review 2020 Annual Report. Division of Maternal and Child Health, Kentucky Cabinet for Health and Family Services. https://chfs.ky.gov/agencies/dph/dmch/Documents/MMRAnnualReport.pdf.

13. Macinko, J., Starfield, B., & Shi, L. (2007). Quantifying the health benefits of primary care physician supply in the United States. International journal of health services : planning, administration, evaluation, 37(1), 111–126. https://doi.org/10.2190/3431-G6T7-37M8-P224

14. Ricketts, T. C., & Holmes, G. M. (2007). Mortality and physician supply: does region hold the key to the paradox? Health services research, 42(6 Pt 1), 2233–2323. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1475-6773.2007.00728.x

15. Starfield, B., Shi, L., & Macinko, J. (2005). Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. The Milbank quarterly, 83(3), 457–502. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x

16. Weber, L. (2019, October 10). They enrolled in medical school to practice rural medicine. what happened? Kaiser Health News. https://khn.org/news/kansas-medical-school-rural-health-care/.

Thompson, J. R., Risser, L. R., Dunfee, M. N., Schoenberg, N. E., & Burke, J. G. (2021). Place, power, and premature mortality: A rapid scoping review on the health of women in Appalachia. American journal of health promotion: AJHP, 35(7), 1015–1027. https://doi.org/10.1177/08901171211011388