Teen Pregnancy Stigma: Getting Over the Belly Bump in Juno

Emma Lauf: Hello, my name is Emma Kate Lauf, and today I will be discussing to what extent the film Juno challenges perceptions of teen pregnancy, followed by a discussion-based segment with Mia Fresina. Teen pregnancy in the United States has been highly stigmatized for years, and young mothers are often labeled as sexually unruly or unfit to parent. As Kyra Clarke highlights in her article “Becoming Pregnant,” a pregnant teenager “carries a whole range of vilified meanings associated with failed femininity” and a “disregard for the well-being of the child.” These negative connotations create a sense of judgment toward young mothers, which can be harmful to pregnant women navigating coming of age. And, during an era when visual culture dominates, it’s important to analyze how representations of adolescent girls’ sexualities show how “cultural ideals are embedded into society.” With this in mind, I want to ask: How is teen pregnancy represented in movies, and what kind of messages are being sent to the American public?

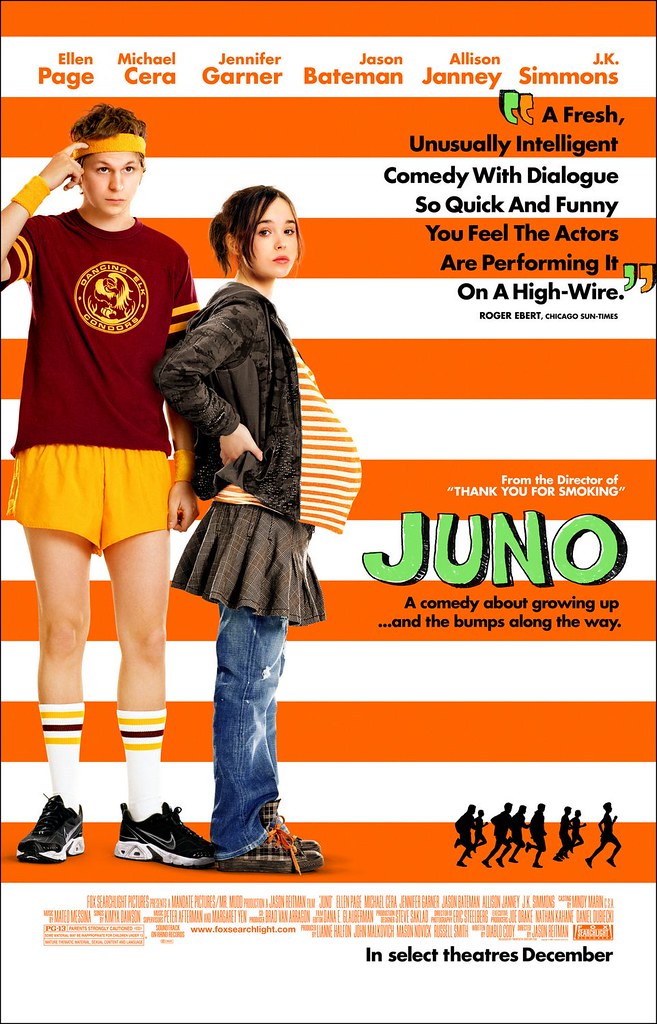

In this podcast, I will be discussing the cinematography in the film Juno, created in 2007 and directed by Jason Reitman, and how it relates to the stigma of teen pregnancy in the United States. I argue that Juno both perpetuates and confronts the negative associations of teen pregnancy. I think this topic not only demonstrates how a film’s cinematography can be a powerful tool to make a statement about society… But it also emphasizes to what extent Juno specifically challenges the stigma of teen pregnancy. First, I will talk about how the film perpetuates the stigma before discussing how it confronts it. So, in what ways does the cinematography in the film stigmatize teen pregnancy? First, I want to provide a little background. The film centers around Juno McDuff, a 16-year-old girl who is pregnant in the early 2000s in Minnesota. After she has unprotected sex with her friend and admirer, Paulie, or “Bleeker,” as she calls him, Juno goes to the store to buy her pregnancy test, which is the opening credit scene.

She walks from her house to the drug store. As she walks, Juno and her surroundings turn into cartoon and drawing styled images. After Juno arrives at the store, the screenplay returns to the regular imaging of real life. Jason Reitman’s choice to switch Juno’s aura to a cartoon right after she suspects she might be pregnant is purposeful. Because animation and cartoons are so closely tied to innocence and childhood, the film argues that before a woman is pregnant, she is in her youth. When a woman becomes pregnant, her childhood is gone. It would make sense that in the moments when Juno is a cartoon, she’s enjoying her “last moments of innocence.” And, perhaps, enjoyment. She’s only animated for that short period of time, which conveys her fleeting youth. And I think this association characterizes a pregnant teen as abnormal and different from how a young woman “should be” growing.

After finding out that she is pregnant, Juno decides to give up her baby for adoption after finding Mark and Vanessa Lorings, a wealthy couple in the newspaper. Although she feels confident about her decision to give her baby to the Lorings, Juno feels the negative social effects at school for being pregnant. Reitman purposefully uses camera angles of Juno from behind at a low level parallel to her, which draws attention to her classmates who pass her, judging her for her pregnancy. The camera angle creates the effect that the other students are much taller than Juno, which suggests the power they hold over her own self-confidence. The music is mellow and the voices of the other students are loud and overpowering. There are also several closeups of Juno’s pregnant belly, which highlights that her pregnancy is monumental to her and everyone else around her. By “fragmenting her body, the film presents teen pregnancy as a negative and confronting experience,” which increases the negative associations with it.

Now that we’ve examined some ways in which the movie perpetuates the stigma, what are some of the ways that Juno takes issue with and ultimately defies it? At some points in the film, rather than viewing teen pregnancy as wrong or shameful, Juno’s pregnancy “offers a site for thinking through the complexity of intimacy and critiquing sex education.” Before Juno decides to have her baby, she calls an abortion clinic to learn more information. In voiceover, Juno says, “I hate it when adults use the term sexually active. What does it even mean?” Her question pairs with a flashback of a sex education class. The teacher stands in front of a board that has the terms “birds” and “bees,” and she slips a condom over a banana. Juno’s question highlights the “predominance of metaphor in sex education,” with birds, bees, and bananas all “excluding terms from the actual teen body from the classroom.”

The scene demonstrates that Juno does have knowledge of contraception, but that a lack of a comprehensive sex education keeps young women’s sexuality taboo. Even so, Juno actively avoids the shame. She’s unafraid to ask questions and talk to her parents early on in her pregnancy about it. In this way, as “pregnant, visible, shameless and not distraught,” Juno doesn’t show “despair, helplessness, or angst,” unlike the typical negatively portrayed teen pregnancy trope. Juno’s confidence and agency to fight the taboo of pregnant teens therefore works to diminish the stigma associated with teen pregnancy. After giving birth at the end of the film, Juno writes her bike to sing a song with Bleeker as if her pregnancy never even happened. Reitman utilizes the filmic element of voiceover, in which Juno ends with a monologue of her own, saying how “normalcy isn’t [her] style,” but she’s okay with that.

In this moment, Juno shows that becoming pregnant is almost reversible. She disrupts the linear idea that there is a link between a pregnant teenage body and motherhood. Although her pregnancy presents challenges, it doesn’t stop her from attending classes or planning to go to college. The voiceover allows Juno to narrate her own story and gives her character a sense of power and development. As girls are becoming more confident talking about sex and the ownership of their bodies, Juno is no exception as she confronts the stigma of teen pregnancy.

Those are the ways in which the film sustains and opposes the stigma of teen pregnancy. I think overall, the film “reinstates a traditional discourse cautioning girls that sex [is] dangerous,” evident through the cartoon style depicting a loss of innocence, as well as the threat of overwhelming judging from peers. However, the film also challenges these negative associations. Juno’s lack of shame and critique of sexual education systems, as well as ending the film with a reversion back to Juno’s pre-pregnancy activities makes a statement that perhaps there is no “correct” way to go about teen pregnancy, and that there are “multiple ways to embody sexuality and identity.” That was my own analysis about the film Juno and how it relates to perceptions of teen pregnancy. And now I would like to transition to a more discussion-based segment of this podcast.

I sat down with a friend of mine. Her name is Mia Fresina, and she’s a sophomore at UNC majoring in Women’s and Gender Studies and Math. I wanted to have a conversation with her about why she pursued this line of study and what her perspective is on pregnant teens’ representation in film. Is it an accurate portrayal? Is it typical? Is there a trope that’s overdone? What can they do to improve it? Here’s what she had to say.

Mia Fresina: I think the pregnant teen trope in media today is usually only done one way. I think it’s like this horrible thing that happens to the girl. It’s either this no-good guy who did it to her, or she is some kind of delinquent. I think there’s just not a lot of diversity, not a lot of representation of different experiences. I think also you could look at it from a racial perspective. If it’s a white girl, it’s usually done one way. If it’s a black girl, it’s done another way… Or a Hispanic girl. It’s usually heavily influenced by race. I think just more representation of diverse experiences would do a lot of good in general.

Lauf: Speaking of a lack of diverse experiences, it sounds like a lot of women growing up had a similar experience of a non-comprehensive sex education. I asked Mia what hers was like, and she definitely reinforced this idea.

Fresina: I think sex education in the United States is really just terrible. I would say that growing up in North Carolina, it was probably especially bad. I think that it’s very focused on certain things. I remember learning that I would get a period, and I remember learning not to have sex. But I don’t remember learning any other aspect of what will happen to my body. They really just encouraged you not to, and I think that just leads to a lot of problems later on in life.

Lauf: In light of the Supreme Court overturning Roe v. Wade, I wanted to know if Mia had any thoughts on not only what this means for pregnant teens, but also how clinics can best support them.

Fresina: The Supreme Court’s decision to overturn Roe v. Wade is just a huge step back for our entire country. Overturning Roe v. Wade just means that people who are pregnant will probably still be getting abortions. They’ll just be in unsafe ways. And if they don’t get the abortions, then they’re stuck in this cycle of poverty or abuse or whatever reason they wanted to have the abortion. Education is really important right now. We were talking about how sex education is just really bad in the U.S. If the clinics kind of filled in the holes that the educational system in the U.S. left… I think they already do this to a certain degree, but maybe an increase in providing contraceptives for people who can’t access them on their own. Otherwise, I really think that the clinics are doing the best they can.

Lauf: Listeners, I think it’s clear that sexuality for girls is, according to Willis, “complicated by social discourses that pronounce girls as powerful subjects but simultaneously impose constraints on their diverse sexual existences.”1 Juno’s story portrays this reality as she navigates being a pregnant teen. I am personally grateful for art forms like film that explore these complex perspectives on topics like teen pregnancy. And I really hope you enjoyed this podcast about perceptions of teen pregnancy in Juno. You can reach out to me on most socials @emmakatelauf with any thoughts or questions.

Sources

1. Willis, 252.

Clarke, K. “Becoming Pregnant.” Feminist Media Studies, Vol. 15, No. 2 (2014): 257–270. Accessed March 21, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1080/14680777.2014.945606.

Juno. Directed by Jason Reitman. Mandate Pictures, 2007. Film.

Willis, Jessica L. “Sexual Subjectivity: A Semiotic Analysis of Girlhood, Sex, and Sexuality in the Film Juno.” Sexuality & Culture, Vol. 12, No. 4 (2008): 240–256. Accessed March 21, 2022. https://doi.org/10.1007/s12119-008-9035-9.