Digital Modification on Social Media: How Does the Content You Engage with Affect Your Body Image?

Abstract

Digital modification on social media is rising, creating a new societal ideal for beauty that is not naturally attainable (Tiggemann, 2004). Various studies show that this has led to a decrease in body image (de Valle et al., 2021). In my research, I compared how viewing a digitally altered image versus posting a digitally altered image impacts an individual’s self-perception. I conducted this research by sending out a survey through The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill’s campus. It proposed questions regarding demographics, social media usage, and the participant’s exposure to digital modification. Using the data from this survey, I concluded that the students at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill have a more negative self-perception viewing a digitally modified image than when they post a digitally modified image.

Introduction

The digital modification of a photo, also known as editing, can range from built-in filters to warping images. With Instagram and Snapchat filters, users can change the tone of a photograph or smooth their skin. However, there are many other apps where users may essentially “photoshop” an image to enlarge their breasts, lips, and eyes; while shaving off centimeters from their thighs, waists, or arms (Tiggemann, 2022). Digital modification has expanded and, in an attempt to copy traditional media content, it has become a standard online (Chua & Chang, 2016; Fox & Rooney, 2015; Fox & Vendemia, 2016; Lonergan et al., 2019; McLean et al., 2015). In my research, I compare how viewing an edited photo and posting an edited photo affects the participant’s body image. Many women and girls report spending a substantial amount of time and effort curating pictures to upload on social media. They seek the most flattering angle, take multiple shots, and edit the photo with filters and apps (Bij de Vaate et al., 2018; Chua & Chang, 2016). Consequently, although the social media environment consists mainly of peers who come in a range of shapes and sizes, it presents idealized and unrealistic images for all (Tiggemann, 2022).

Social media has created a new way for the societal ideals of beauty, which emphasize thinness and youth, to be distributed (Rodgers & Melioli, 2016; Tiggemann, 2004). Since celebrities, family, friends, and peers are all placed on the same platform, the content posted on social media appears more realistic (Naderer et al., 2021). However, users tend to post the most attractive, edited parts of themselves to present perfection. MacCallum and Widdows described the effects of the idealized images as “the perfect image on the page feeds into our imaginings of the perfect ideal we are seeking to embody.” When people compare their faults with an idealized version of others, they develop a negative body image and sense of inadequacy (de Valle et al., 2021). Self-perception is a core aspect of psychological well-being. A negative self-image may not only increase an individual’s risk of engaging in appearance-altering behaviors, such as dysfunctional eating, it can also lead to concerning emotional difficulties, such as distress and depression (Paxton et al., 2006). Given the current research on digital modification and its impact on self-image, I hypothesize that consuming edited photos negatively impacts the user’s body image more than if they were to produce them.

Methodology

I conducted a Qualtrics survey to compare how a participant’s body image is affected if they view a digitally altered image versus post a digitally altered photo. I specifically focused on comparing the two because there is limited research on the effects of posting edited images.

I included four questions about demographics to understand my audience better:

- How old are you (in years)?

- What race/ethnicity do you most identify with?

- What sex were you assigned at birth?

- What is your gender identity?

I included three questions regarding social media usage to evaluate the person’s exposure to digital modification:

- Do you have social media?

- Which social media applications do you have?

- How much time, on average, do you spend on social media a week?

I included six questions regarding the prevalence of digital modification on social media to test if digital modification has a different effect on body image if you view the image versus post it (Note: The asterisk (*) indicates that the questions were asked based on a sliding scale from 0 to 100, with 0 representing “I strongly disagree with the statement provided” and 100 representing “I strongly agree with the statement provided.”):

- Do any creators you follow frequently use digital modification (i.e., filters or Photoshop) on the photos they post?

- Viewing a digitally modified image negatively affects the way I view my own body image.*

- Viewing a digitally modified image positively affects the way I view my own body image.*

- Do you frequently use digital modification (i.e., filters or Photoshop) on the photos you post on social media?

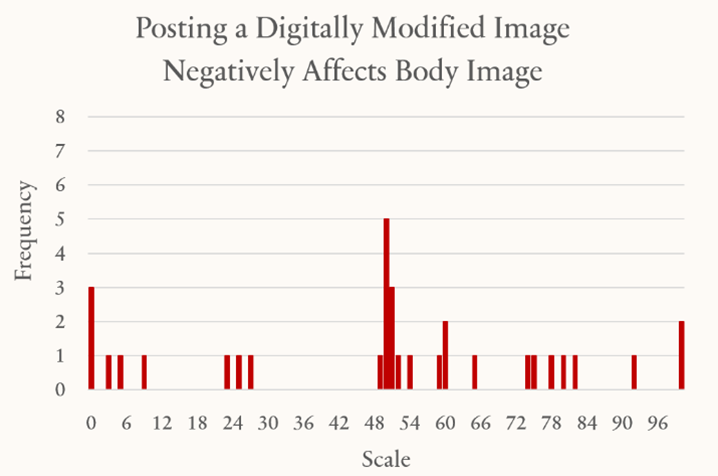

- Posting a digitally modified image negatively affects the way I view my own body image.*

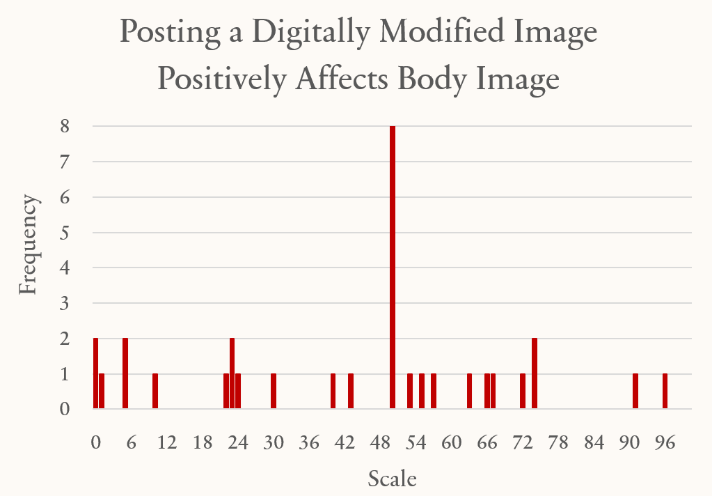

- Posting a digitally modified image positively affects the way I view my own body image.*

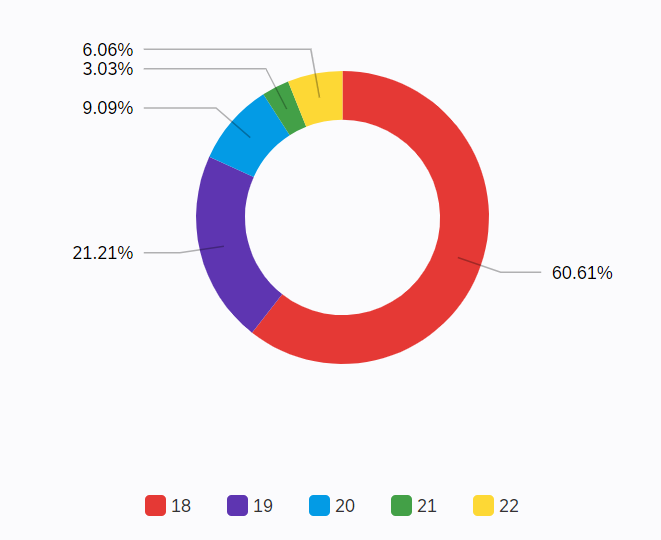

Figure 1: How old are you (in years)?

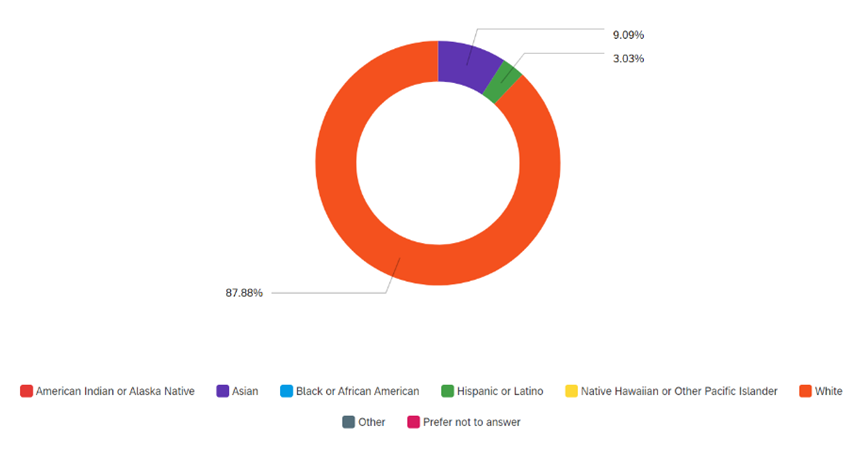

Figure 2: What race/ethnicity do you most identify with?

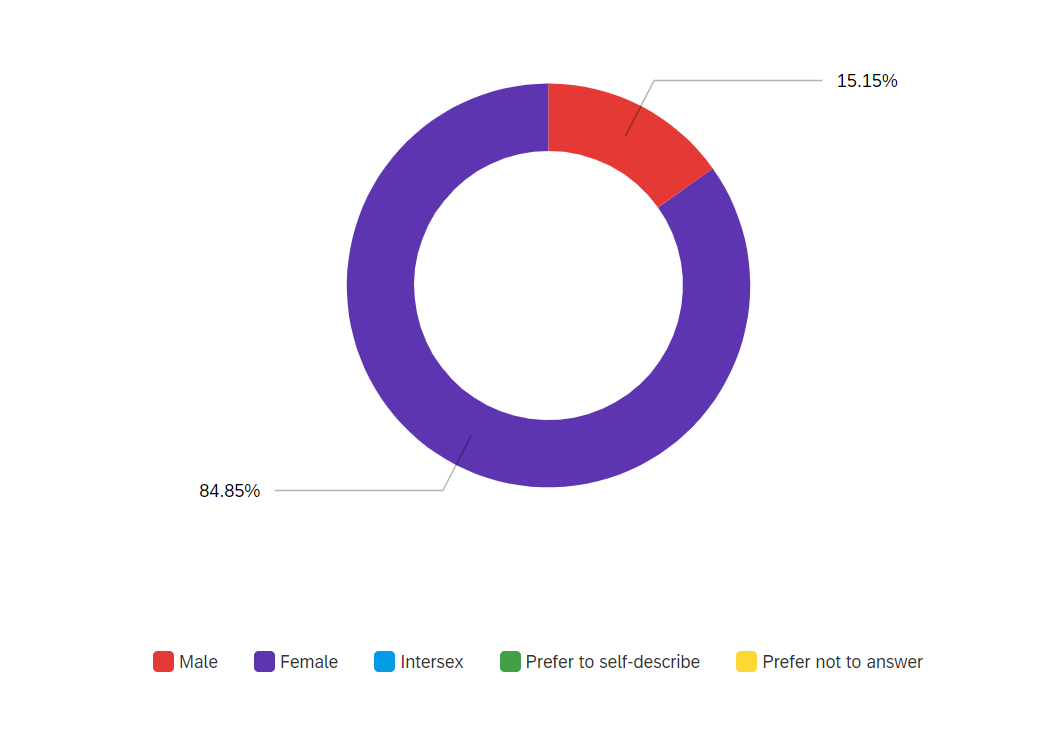

Figure 3: What sex were you assigned at birth?

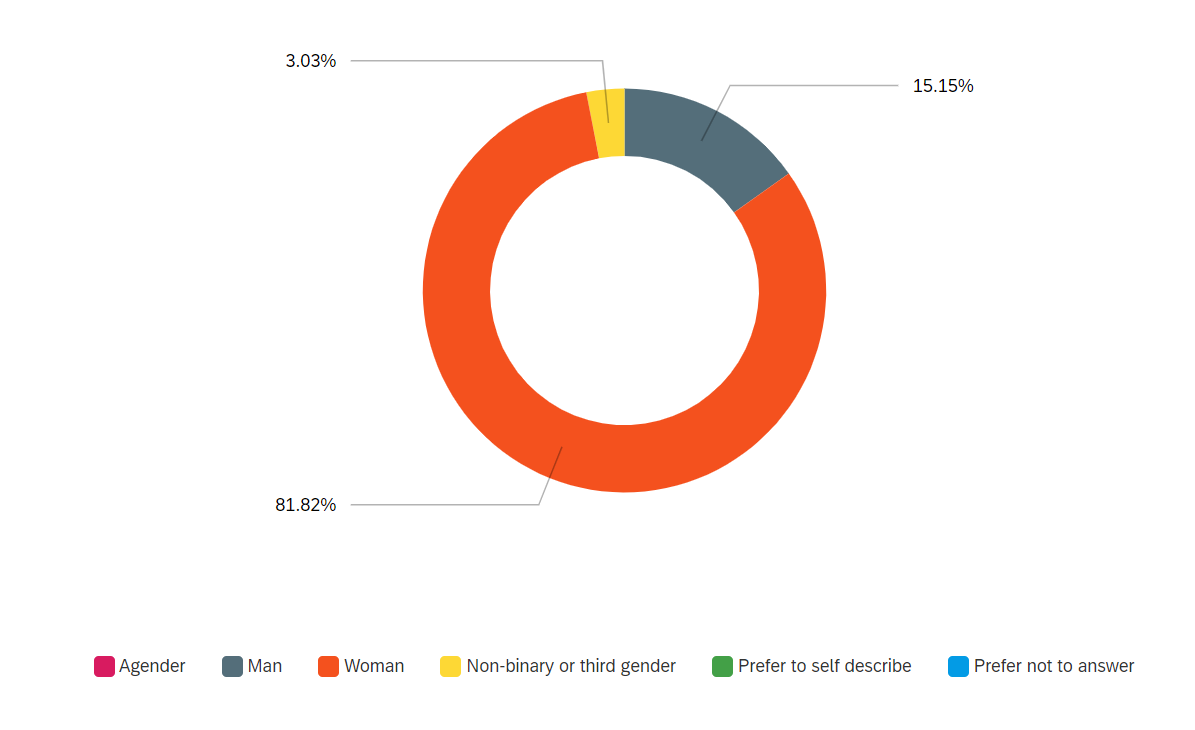

Figure 4: What is your gender identity?

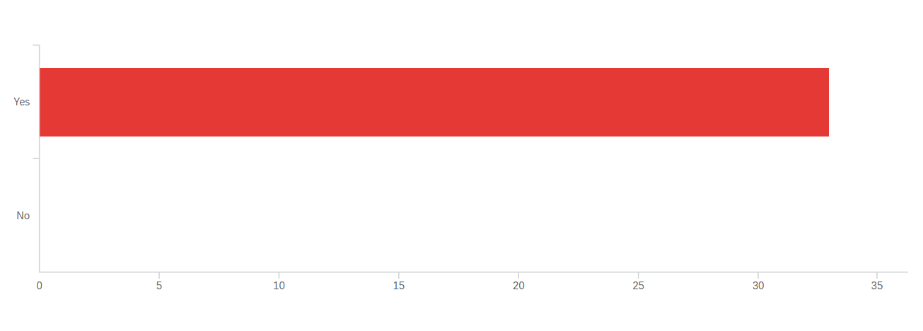

Figure 5: Do you have social media?

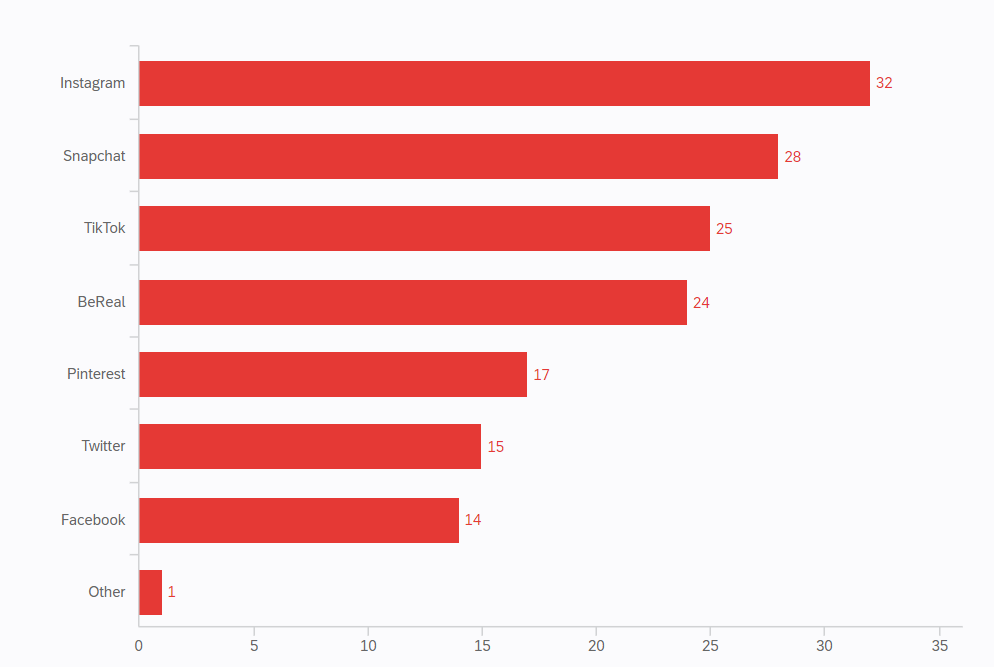

Figure 6: What social media applications do you have?

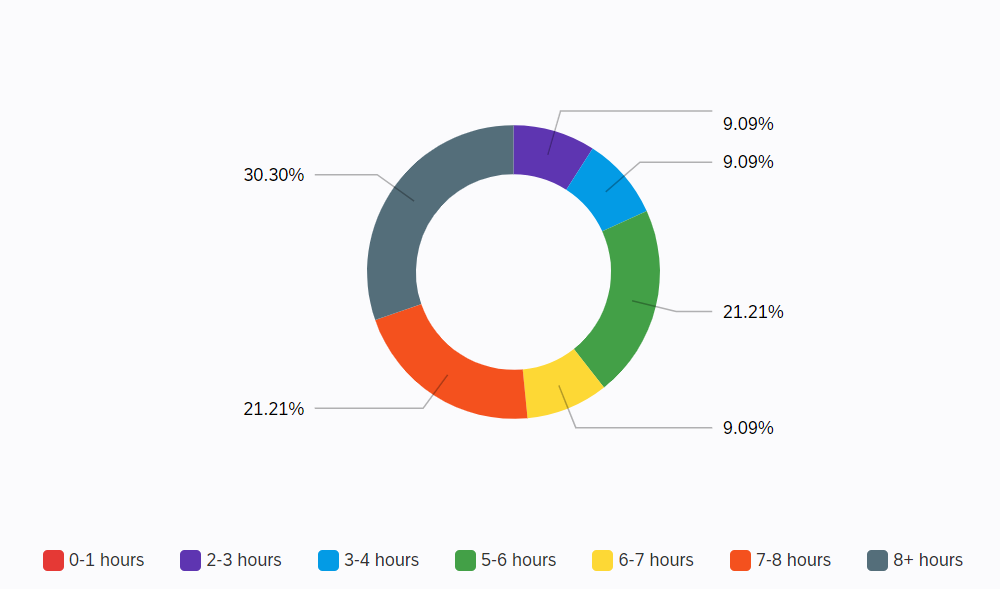

Figure 7: How much time, on average, do you spend on social media per week?

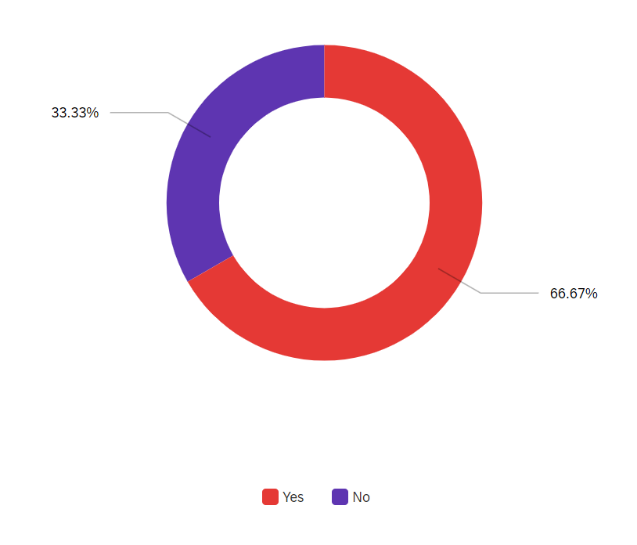

Figure 8: Do any creators you follow frequently use digital modification (i.e., filters or Photoshop) on the photos they post?

Figure 9

Figure 10

Findings

As reflected in the data, this study did not reach a large demographic of students. Unfortunately, this means that the data may not accurately reflect the entire student body at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill. However, I will continue to analyze the data as if it is about the entire student body. The data shows that Instagram is the most prevalent social media platform among students at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill, with 96.97% of respondents using it. This figure is important because Instagram users frequently engage with and in digital modification.

Additionally, 51.51% of students spend over seven hours on social media per week, which increases their risk of exposure to digitally modified photos. I also found that 66.67% of the students follow creators that frequently use digital modification. These figures confirm the pervasiveness of editing on social media. However, I suspect the number of individuals engaging in digital modification is higher. According to a study by Nightingale et al. (2015), when presented with a digitally altered image—half of the participants did not detect that it was manipulated.

Students were more likely to agree that viewing an edited photo negatively affects their body image. I came to this conclusion because the “viewing a digitally modified image negatively affects body image” graph appears skewed to the left, indicating that more students agreed with the statement. On the other hand, the “viewing a digitally modified image positively affects a body image” graph appears skewed to the right, which implies that more students disagreed with the statement. The students’ responses did not align with the research I conducted before this study. The data also shows that 81.82% of the students do not frequently use digital modification themselves. This lack of use may be a future area of study since all previous research pointed to editing becoming a standard for everyone.

I also found that posting a digitally modified image neither negatively nor positively affects the user’s body image. Neither graph is skewed, indicating that students were just as likely to agree or disagree with both statements. These results did not support prior research, as in a study conducted by Wick & Keel (2020), it was found that women who posted digitally altered photos had greater eating disorder cognitions, as opposed to the control condition and those who posted unedited images. Since editing photos requires the individual to view themselves in the third person, they harbor a more critical lens. It is the essence of self-objectification (Fredrickson & Roberts, 1997). However, we must consider that most students in the study stated they do not frequently edit themselves, which might have affected the outcome of this question.

Given my results, I concluded that students at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill feel more negatively about their body image when they view a digitally modified image than when they post a digitally modified one.

Proposed Solutions

There are three proposed solutions to digital modification. These include education on digital modification, disclaimer labels, and increased diversity in models. One suggestion was for schools to implement education programs that include components focusing on media literacy and the artificial nature of images (MacCallum & Widdows, 2016). However, a study by Nightingale et al. (2015) found that people’s knowledge of image manipulation did not improve their ability to detect and locate the alterations. Simply being aware that some of the images are modified does not mean we are better at recognizing them, suggesting that media literacy training may not be enough (MacCallum & Widdows, 2016).

Another suggestion was to add a disclaimer label on digitally modified photos—stating that it has been altered. However, this labeling had the opposite effect as intended, as it increased the desire to aspire to the ideal portrayed (MacCallum & Widdows, 2016). This reversal may occur because disclaimer labels call more attention to the image, causing deeper processing of it and reinforcing our conception of the ideal (Selimbegovie & Chatard, 2015). Others suggest that a greater diversity of models on social media might broaden the beauty ideals we aspire to. However, beauty ideals are culturally constructed and carry meaning and value. Therefore, it is difficult to challenge them (MacCallum & Widdows, 2016). Nevertheless, this is the most promising solution and may help decrease the negative self-perception that many individuals experience due to the unrealistic beauty standards within society.

References

Bij de Vaate, A. J., Veldhuis, J., Alleva, J. M., Konijn, E. A., & van Hugten, C. H. (2018, August). Show your best self(ie): An exploratory study on selfie-related motivations and behavior in emerging adulthood. Telematics and Informatics 35(5), 1392-1407. Retrieved from ScienceDirect: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tele.2018.03.010

Chua, T. H., & Chang, L. (2016, February). Follow me and like my beautiful selfies: Singapore teenage girls’ engagement in self-presentation and peer comparison on social media. Computers in Human Behavior, 55(A), 190-197. Retrieved from ScienceDirect: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2015.09.011

de Valle, M. K., Gallego-García, M., Williamson, P., & Wade, T. D. (2021, December). Social media, body image, and the question of causation: Meta-analyses of experimental and longitudinal evidence. Body Image, 39, 276-292. Retrieved from ScienceDirect: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2021.10.001

Fox, J., & Rooney, M. C. (2015, April). The Dark Triad and trait self-objectification as predictors of men’s use and self-presentation behaviors on social networking sites. Personality and Individual Differences, 76, 161-165. Retrieved from ScienceDirect: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.paid.2014.12.017

Fredrickson, B. L., & Roberts, T.-A. (1997, June). Objectification theory: Toward understanding women’s lived experiences and mental health risks. Psychology of Women Quarterly, 21(2), 173-206. Retrieved from Sage Journals: https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1471-6402.1997.tb00108.x

Graphing/Charting and General Data Visualization App. (2022). Retrieved from Meta Chart: https://www.meta-chart.com/pie

Lonergan, A. R., Bussey, K., Fardouly, J., Griffiths, S., Murray, S. B., Hay, P., . . . Mitchison, D. (2020, April 7). Protect me from my selfie: Examining the association between photo‐based social media behaviors and self‐reported eating disorders in adolescence. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(5), 755-766. Retrieved from Wiley Online Library: https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23256

MacCallum, F., & Widdows, H. (2018). Altered Images: Understanding the Influence of Unrealistic Images and Beauty Aspirations. Health Care Analysis, 26, 235-245. Retrieved from Springer Link: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10728-016-0327-1

McLean, S. A., Paxton, S. J., Wertheim, E. H., & Masters, J. (2015, August 27). Photoshopping the selfie: Self photo editing and photo investment are associated with body dissatisfaction in adolescent girls. International Journal of Eating Disorders, 48(8), 1132-1140. Retrieved from Wiley Online Library: https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.22449

Microsoft. (2022). PowerPoint. Retrieved from Microsoft: https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/p/powerpoint/cfq7ttc0hlg1?activetab=pivot:overviewtab

Naderer, B., Peter, C., & Karsay, K. (2021, June 23). This picture does not portray reality: developing and testing a disclaimer for digitally enhanced pictures on social media appropriate for Austrian tweens and teens. Journal of Children and Media, 16(2), 149-167. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online: https://doi.org/10.1080/17482798.2021.1938619

Nightingale, S. J., & Watson, D. G. (2015). Photography or ‘fauxtography’: Exploring people’s ability to detect manipulations in digital images. . Amsterdam, NL: Paper presented at the international convention of psychological science.

Paxton, S. J., Neumark-Sztainer, D., Hannan, P. J., & Eisenberg, M. E. (2010, June 7). Body Dissatisfaction Prospectively Predicts Depressive Mood and Low Self-Esteem in Adolescent Girls and Boys. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 35(4), 539-549. Retrieved from Taylor & Francis Online: https://doi.org/10.1207/s15374424jccp3504_5

Qualtrics. (2022). Retrieved from Qualtrics: https://www.qualtrics.com

Rodgers, R. F., & Melioli, T. (2016). The Relationship Between Body Image Concerns, Eating Disorders and Internet Use, Part I: A Review of Empirical Support. Adolescent Research Review, 1(2), 95-119. Retrieved from Springer Link: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40894-015-0016-6

Selimbegović, L., & Chatard, A. (2015, January). Single exposure to disclaimers on airbrushed thin ideal images increases negative thought accessibility. Body Image, 12, 1-5. Retrieved from ScienceDirect: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2014.08.012

Tiggemann, M. (2004, January). Body image across the adult life span: stability and change. Body Image, 1(1), 29-41. Retrieved from ScienceDirect: https://doi.org/10.1016/s1740-1445(03)00002-0

Tiggemann, M. (2022, June). Digital modification and body image on social media: Disclaimer labels, captions, hashtags, and comments. Body Image, 41, 172-180. Retrieved from ScienceDirect: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bodyim.2022.02.012

Wick, M. R., & Keel, K. P. (2020, May 5). Posting edited photos of the self: Increasing eating disorder risk or harmless behavior? International Journal of Eating Disorders, 53(6), 864-872. Retrieved from Wiley Online Library: https://doi.org/10.1002/eat.23263