Closing the Gap: Tackling the Maternal Mortality Disparity in North Carolina

Shalon Irving, a vibrant, well-educated Black woman, gave birth to her daughter, Soleil, on January 3rd, 2016. In the days following her daughter’s birth, Shalon went to the hospital four times for pregnancy-related complications such as hypertension and other cardiovascular issues such as heart attacks and strokes. However, no one listened to her concerns. Three weeks after Soleil was born, Shalon was dead. Her story mirrors that of many other Black women in America. In Shalon’s case, she experienced a process known as “weathering,” which contributed to her negative health outcome. Weathering is a term coined by Dr. Arline Geronimus to describe the physical and mental effects of systemic oppression. She determined that prolonged exposure to inequity would increase a Black woman’s allostatic load, which would make her more susceptible to adverse health outcomes as chronic stress weakens the body (1992). Had providers been aware of this phenomenon or listened to Shalon when she expressed her concerns repeatedly, the outcome may have been very different.

The issue of maternal mortality in the United States is complicated and can be attributed to causes at several levels: individual, interpersonal, community, and societal. The Socioecological Model for Prevention identifies that these levels are essential for providers and other health officials to understand to prevent adverse health outcomes for marginalized communities, especially Black women (Njoku et al., 2023). This core principle is at the heart of respectful maternity care, encompassing culturally competent care. Culturally competent care requires providers to listen to their patients’ health concerns and provide information on their susceptibility to medical conditions that can make pregnancy dangerous, all while being mindful of their cultural backgrounds, disparities they face, and how these factors impact their health. When providers neglect to consider such factors, the result is the equivalent of a death sentence.

This article will examine a three-step process to effectively ensure that Black women have access to culturally competent care, helping to close the maternal mortality disparity gap. The maternal mortality disparity gap is the disparity between the number of pregnancy-related deaths for non-Hispanic White women and non-Hispanic Black women. The first step of this process involves creating standardized care checklists that uphold the principles of respectful maternity care. The second entails properly training providers according to these new guidelines. The final step revolves around building trust within the community as part of that training and a public evaluation system that incentivizes hospitals and clinics to uphold these guidelines. This proposal emphasizes changing the culture of healthcare and addressing the root of the problem: a lack of culturally competent care, rather than policy recommendations. Though that is not the purpose of this proposal, changing the culture of medicine without proper policy initiatives to improve maternal health outcomes would likely result in minimal impact. Thus, the proposed process must also be accompanied by these initiatives.

Maternal Mortality in North Carolina

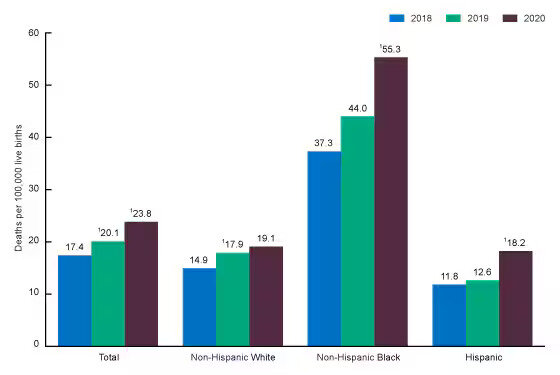

Statistics taken from the North Carolina’s Maternal Mortality Review Committee (NC MMRC), which is responsible for reviewing pregnancy-related deaths and providing recommendations to address North Carolina’s maternal mortality crisis, reveal the prevalence of a maternal mortality disparity gap within North Carolina in their most recent report published in 2021. In 2020, the United Health Foundation (2021) reported that North Carolina ranked 29th in maternal mortality nationwide. While the data on how many of these deaths were preventable is not readily available to the public, the NC MMRC independently reviewed pregnancy-related deaths from 2014 to 2016. To provide a better understanding of pregnancy-related mortality disparities over time, the NC MMRC used aggregated data from 2001 to 2016 and reported that, from 2013 to 2016, Black women were almost twice as likely than White women to die due to pregnancy-related causes (NC MMRC, 2021, p.13). While the disparity ratio is significant in and of itself, approximately 70 percent of these deaths were deemed preventable by the NC MMRC (NC MMRC, 2021, p. 14). This finding strongly implies that there are effective ways to address this disparity. However, a report on the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention’s more recent data found that Black women in North Carolina were three times more likely to die due to pregnancy-related complications (Hoyert, 2020). Figure 1 highlights not only an increase in maternal mortality, but also an increase in the maternal mortality disparity from 2018 to 2020.

Figure 1. Maternal mortality rates, by race and Hispanic origin: United States, 2018–2020 (Hoyert, 2020)

There are several factors in North Carolina that have contributed to such a significant maternal mortality disparity. When examining the leading causes of pregnancy-related deaths in North Carolina, such as cardiovascular diseases, hemorrhages, embolisms, and similar medical conditions, it becomes evident that early detection plays a crucial role in treating such conditions. Early detection depends on the individual’s access to healthcare. North Carolina has the 10th highest uninsured population in the nation; roughly 10.7 percent of the population is uninsured, with the highest concentration of uninsured North Carolinians living in almost non-White-majority counties (North Carolina Justice Center [NCJC], 2021). In addition to a high uninsured population, North Carolina also faces a critical lack of rural health facilities, vastly limiting the options pregnant patients in rural counties have, putting more pregnant and non-pregnant people at risk. Without regular and relatively easy access to healthcare services, high-risk conditions go undiagnosed, jeopardizing risk management measures.

For the best maternal health outcomes, a patient must have access to quality healthcare. For Black women, regularly seeing a provider is the first of many steps to receiving adequate healthcare, but it is not enough. The prevalence of bias among providers and the lack of understanding of the role of chronic stress on a Black woman’s health poses severe risks to Black women. Providers must understand that without acknowledging this, providing care is not the same as providing quality care. The convergence of such distinctive factors puts Black women in North Carolina at higher risk during childbirth when compared to their White counterparts, which requires that extra precautions be taken to create positive clinical outcomes.

Existing Recommendations in North Carolina

There are several sets of recommendations for improving maternal health outcomes, especially from the NC MMRC. In their 2021 report, they have provided 188 recommendations, with more than a third designated for providers (NC MMRC, 2021, p.16). Such recommendations include better adherence to clinical guidelines and protocols, further education and training, better postpartum screenings, and enhanced coordination and communication (NC MMRC, 2021, p.16). The NC MMRC has also issued recommendations for patients and their families, primarily centered on enhancing patient education. Additionally, they have made systems recommendations that encompass establishing consistent guidelines for various health issues, adopting patient-centered care practices, expanding mental health support, and providing implicit bias training for providers. The NC MMRC also recommends that healthcare facilities improve care coordination, implement Alliance for Maternal Health safety bundles, and improve sub-specialist access, among other measures (NC MMRC, 2021, p.19). A small percentage of the NC MMRC’s recommendations were targeted at the broader community, emphasizing disseminating information regarding warning signs of severe maternal morbidity, providing CPR training, and providing progressive community outreach to increase awareness of available healthcare services within the community.

One primary recommendation often proposed to decrease maternal mortality in the State of North Carolina is Medicaid expansion. This suggestion entails broadening the eligibility criteria for Medicaid, allowing more low-income North Carolinians to access healthcare. Given North Carolina’s high uninsured population and limited access to rural health facilities, the North Carolina State Legislature passed a bill expanding Medicaid in early 2023, with eligible North Carolinians being able to enroll as of December 1st. In North Carolina, this means that a lower percentage of the population will be uninsured, existing rural health facilities will face a lower risk of needing to shut down due to lack of payment, and more women will receive appropriate levels of care before and after pregnancy to ensure the best health outcomes for both the mother and the baby. Research conducted by Eliason (2020) at the Columbia University School of Social Work suggests that Medicaid expansion was associated with decreasing maternal mortality by 7.01 maternal deaths per 100,000 live births compared to non-expansion states, which is a significant improvement. This effect was concentrated mainly among non-Hispanic Black women, highlighting the policy’s potential for decreasing the maternal mortality disparity in North Carolina. As Medicaid expansion in North Carolina is so new, there is little data on its effects in North Carolina. Still, results from expansion states maintain the promising nature of the policy.

Although North Carolina has made certain advancements in the aforementioned areas, the persisting disparity in maternal mortality underscores the inadequacy of measures taken thus far due to existing issues with implicit bias and systemic racism. To address this within healthcare, organizations like the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists have been raising awareness and providing resources to understand the problem better. However, much of the NC MMRC’s recommendations remain unimplemented and largely depend on individual healthcare facilities taking the initiative. The proposal outlined below is derived from the recommendations made by the NC MMRC with the goal that all healthcare facilities in North Carolina take these recommendations seriously.

Step One: Creating Standardized Care Checklists

The first step of my process involves building standardized care checklists for hospitals and providers using the World Health Organization’s Respectful Maternity Care framework as a model for North Carolina’s checklists. Standardized care checklists are clinical best practice guidelines for providers to follow when handling various clinical situations, however, they can also be designed to close knowledge gaps about marginalized women and maternal mortality. The World Health Organization (WHO) has identified the following elements as part of their framework: evidence-based practices for routine care and management of complications, actionable information systems, functioning referral systems, effective communication, respect and preservation of dignity, emotional support, competent and motivated personnel, and the availability of essential physical resources (WHO, 2016). These elements should be centered in any care checklist development process as they are crucial and address most of NC MMRC’s recommendations.

It, it is imperative to conduct a baseline evaluation of how providers and healthcare facilities in North Carolina align with the standards outlined by the WHO to develop the highest quality standardized care checklists (SCC). Such an assessment aims to identify any inconsistencies in clinical practice, with the primary objective of creating care checklists that effectively address and rectify inconsistencies. A systematic and thorough evaluation would require significant resources, but the work of the NC MMRC provides an excellent starting point. In partnership with healthcare providers and facilities, the NC MMRC should produce a report identifying current clinical guidelines. This report should also include a comparison of current practices and the recommendations outlined by the NC MMRC, which the initial report in 2021 does not provide. This additional information would allow for better identification of the gaps that must be addressed.

Following the completion of the initial evaluation, the subsequent steps of the SCC development process should closely adhere to the framework established by the Clinical Practice Guideline development process, designed by the Institute of Medicine (IOM). The Institute of Medicine (2011) defines clinical practice guidelines as “statements that include recommendations intended to optimize patient care that are informed by a systematic review of evidence and an assessment of the benefits and harms of alternative care options.” (p. 4) The IOM identifies that for guidelines to be trustworthy, they should meet the following criteria:

Be based on a systematic review of the existing evidence; be developed by a knowledgeable, multidisciplinary panel of experts and representatives from key affected groups; consider important patient subgroups and patient preferences, as appropriate; be based on an explicit and transparent process that minimizes distortions, biases, and conflicts of interest; provide a clear explanation of the logical relationships between alternative care options and health outcomes, and provide ratings of both the quality of evidence and the strength of the recommendations; and be reconsidered and revised as appropriate when important new evidence warrants modifications of recommendations. (p. 5)

To develop care checklists that adhere to these foundational principles, the IOM recommends the incorporation of diverse and informed opinions. Consequently, it is highly recommended that the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services facilitate a collaborative, public-private partnership. This partnership should include members of the NC MMRC, licensed maternity care providers across the state, doulas and midwives who offer community-based maternal support, key stakeholders, and representatives of the population expected to be affected by the proposed SCCs. The task force in charge of creating SCCs should meet quarterly and create designated subcommittees based on each identifiable gap from the initial evaluation. Each subcommittee should focus on effectively transforming relevant NC MMRC recommendations into SCCs. In addition to creating distributable SCCs, each SCC should be accompanied by a critical evaluation, which should include a summary of relevant evidence for why this is the best practice, potential benefits and harms of the SCC, and a description and explanation of any differences in opinion (IOM, 2011, pp. 7-8).

Once SCCs have been created and agreed upon by the task force, the North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services (NC DHHS) would be responsible for distributing checklists among all hospitals in North Carolina that provide labor and delivery care. The Joint Commission, a non-profit that regularly examines hospitals to make sure they can retain their accreditation status, would bear the burden of ensuring hospitals and providers are meeting these standards. If standards are not being met, a hospital should have one year to remedy identified gaps or risk losing its accreditation.

Step Two: Training Providers in SCCs

The second step of the process is to provide training to providers so that they can adequately fulfill the Standardized Care Checklists (SCCs) while simultaneously building trust among community members. Members of the task force licensed to provide healthcare in the state of North Carolina should be responsible for formulating a comprehensive training program with a particular focus on building cultural competency. As such, this training program would aim to equip healthcare providers with the required knowledge and proficiency to apply SCCs properly. This training program should include real-world scenarios where the SCCs would be applicable through demonstrations on a standardized patient. Standardized patients are “individuals who pretend to be patients in a standardized and consistent way in a formal examination setting, or in an unannounced clinical practice to assess the performance of medical workers” (Wang et al., 2021). Providers will be compensated for completing the training and evaluated on their adherence to the checklist using the aforementioned standardized patient. Upon approval from the creators of the training program, providers who pass their evaluations may subsequently undergo advanced training to become instructors of this program. This process will ensure that providers are well-versed in these new guidelines.

For example, the training program could be based on resources from the Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health (AIM). AIM was created to lower maternal mortality rates, and a significant part of its mission is to provide safety bundles to providers across the nation. Safety bundles are sets of clinical guidelines for various potential pregnancy complications. Providers in North Carolina have already received some of AIM’s safety bundles along with relevant training materials, which include information on the following conditions: severe hypertension in pregnancy, obstetric hemorrhage, cardiac conditions in obstetrical care, and substance use disorder (Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health, 2022). NC DHHS should collaborate with AIM and members of the NC MMRC who are licensed to practice medicine in North Carolina to create and provide a virtual or in-person training program to implement the care checklists properly.

To further patient education and build community, hospitals should provide maternal and infant care programs led by a hospital provider and a doula at no cost to participants. The program should prioritize instructing patients on self-advocacy within the labor and delivery setting while also setting expectations of providers’ roles and responsibilities with the new SCCs. Additionally, patients should be provided with the following in an easily accessible format:

- standard infant care information

- information on postpartum depression and postpartum anxiety

- a list of warning signs for leading causes of maternal mortality

- a method of recourse if patients do not feel that provider care meets the standards in the SCC

Concerning establishing an accessible recourse mechanism, it is imperative that patients can submit complaints to a designated entity responsible for overseeing issues related to provider adherence to the newly implemented SCCs. This reporting process should aim to ensure that patients’ concerns are acknowledged and any improper conduct is rectified through appropriate measures, including potential retraining. Having an option of recourse available to patients and providing patients with the listed information allows them to feel a greater sense of empowerment, which ultimately leads to better clinical outcomes as it increases the likelihood of complying with clinical guidelines (Nutbeam, 2008). However, this is contingent on existing health literacy levels, which maternal support groups aim to improve. Since marginalized populations are at higher risk of suffering from low health literacy levels, hospital providers should encourage members of marginalized groups to attend training sessions by ensuring that those leading the sessions are representative of those in their community. The ultimate goal is to create a learning space where group members actively look out for each other regarding warning signs while providing community members access to licensed community-based individuals to reach out to.

Step Three: Establishing a Public Evaluation System

The third and final step of this process is that there must be a public evaluation system where hospitals and clinics are graded according to how well they adhere to the care checklists. The North Carolina Maternal Mortality Review Committee should conduct these evaluations every two years and publish their results on the NCDHHS website for all North Carolinians to access. For example, Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) have created an online database that lists hospitals that have received a “birthing-friendly” designation based on the hospital’s “participation in a statewide or national perinatal quality improvement collaborative program…” and whether a hospital has “…implemented evidence-based quality interventions in hospital settings to improve maternal health” (CMS, 2023). By separating this from the accreditation process, patients have access to this data in a centralized location, allowing them to make the best decision for their care. Publicizing these results in this manner also allows program administrators and others interested in the program to assess the progress made by the program and adjust accordingly.

During the evaluation process, the NC MMRC should examine and consider metrics such as pregnancy-related deaths per hospital, the maternal mortality disparity factor at each hospital, and patient satisfaction. To measure patient satisfaction, a survey similar to the ones administered by CMS, called CAHPS and HCAHPS, should be designed to evaluate maternal healthcare experiences specifically. The survey design should meet quality assurance guidelines and be randomly distributed to North Carolinians who gave birth within the last year. Potential metrics for this survey could be derived from the Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire-18, which measures elements of patient satisfaction, including “general satisfaction, technical quality, interpersonal manner, communication, financial aspects, time spent with the doctor, and accessibility and convenience” (Thayaparan & Mahdi, 2013). Other relatively new measures, like the Patient-Reported Experience Measure of Obstetric Racism (PREM-OR) and the Person-Centered Maternity Care (PCMC) Scale, focus on measuring Black patient satisfaction concerning perceived racism in a clinical setting. Such metrics would provide evaluators with a comprehensive understanding of patient satisfaction and areas of improvement to continue to address any persisting gaps. Evaluators could then take this information to create grading criteria and grade facilities to promote accountability.

Final Thoughts

All North Carolinians deserve to give birth safely. This proposed process is not just about decreasing the disparity factor for Black women. However, that is primarily what the statistics will represent due to a lack of information quantifying the birth experiences of other marginalized groups. Instead, it is about ensuring that all individuals have a safe and nurturing birth experience, but with particular emphasis on Black and Indigenous women, immigrant women, AFAB folks, and other marginalized groups whose experiences often go unnoticed in this country. This proposed process is not the only method to achieve this, but it is meant to be the first step towards a better future where all mothers get to meet their children. Though this is a lofty proposal requiring significant funding and a great deal of collaboration between public and private groups, improving the quality of maternal healthcare in North Carolina is critical to ensuring robust health infrastructure that provides quality healthcare to all North Carolinians, regardless of race.

Sources

Alliance for Innovation on Maternal Health. (2022, October 5). Enrolled states and jurisdictions. https://saferbirth.org/about-us/enrolled-states-and-jurisdictions/

Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services. Birthing-Friendly Hospitals and Health Systems | Provider Data Catalog. (2023). Retrieved December 27, 2023, from https://data.cms.gov/provider-data/birthing-friendly-hospitals-and-health-systems

Eliason, E. L. (2020). Adoption of Medicaid Expansion Is Associated with Lower Maternal Mortality. Women’s Health Issues, 30(3), 147–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.whi.2020.01.005

Geronimus, A. T. (1992). The weathering hypothesis and the health of African-American women and infants: Evidence and speculations. Ethnicity & disease, 2(3), 207–221.

Hoyert, D. L. (2022). Maternal mortality rates in the United States. NCHS Health E-Stats. https://dx.doi.org/10.15620/cdc:113967

Institute of Medicine. (2011). Clinical practice guidelines we can trust. The National Academies Press. https://doi.org/10.17226/13058.

Montagne, R. (2017, December 7). Black Mothers Keep Dying After Giving Birth. Shalon Irving’s Story Explains Why. NPR. https://www.npr.org/transcripts/568948782 .

Njoku, A., Evans, M., Nimo-Sefah, L., & Bailey, J. (2023). Listen to the whispers before they become screams: Addressing Black maternal morbidity and mortality in the United States. Healthcare, 11(3), 438. https://doi.org/10.3390/healthcare11030438 .

North Carolina Department of Health and Human Services. (2023, August 28). Due to budget delay, Medicaid expansion will not launch on Oct. 1. [Press Release}. https://www.ncdhhs.gov/news/press-releases/2023/08/28/due-budget-delay-medicaid-expansion-will-not-launch-oct-1.

North Carolina Justice Center. (2021). Uninsured in North Carolina. Retrieved August 31, 2023, from https://www.ncjustice.org/projects/health-advocacy-project/medicaid-expansion/uninsured-in-north-carolina/.

North Carolina Maternal Mortality Review Committee. (2021). North Carolina Maternal Mortality Review Report. https://wicws.dph.ncdhhs.gov/docs/2014-16-MMRCReport_web.pdf.

Nutbeam, D. (2008). The evolving concept of health literacy. Social Science & Medicine, 67(12), 2072–2078. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.socscimed.2008.09.050.

Thayaparan, A.J., & Mahdi, E. (2013). The Patient Satisfaction Questionnaire Short Form (PSQ-18) as an adaptable, reliable, and validated tool for use in various settings. Medical Education Online, 18(1). https://doi.org/10.3402/meo.v18i0.21747.

United Health Foundation. (2021). Maternal Mortality in North Carolina. America’s Health Rankings. https://www.americashealthrankings.org/explore/measures/maternal_mortality_c/NC .

Wang, J., Zhao, S., Xu, D., Estill, J., Lv, M., Zhao, S., Zhang., Cai, Y., Liao, J., Lu, Y., Wang, X., & Chen, Y. (2021). Developing evidence-based quality assessment checklist for real practice in primary health care using standardized patients: A systematic review. Annals of Palliative Medicine, 10(7), 8232-8241. https://doi.org/10.21037/apm-21-712 .

World Health Organization. (2016). Standards for improving quality of maternal and newborn care in health facilities. https://cdn.who.int/media/docs/default-source/mca-documents/qoc/quality-of-care/standards-for-improving-quality-of-maternal-and-newborn-care-in-health-facilities.pdf.