Calm and Chaos in UNC-Chapel Hill’s Emergency Medicine Department

Abstract

Veronica Chandler’s observation article emphasizes the contrast between the hectic emergencies in an emergency department and the moments of relative peace.

CHAPEL HILL, North Carolina – Four hours in an Emergency Department is a long time, especially when patients are constantly ferried in and out on stretchers. However, four hours capture only half of the eight-hour shift doctors work. In the effort to diagnose conditions and save lives, doctors, nurses, and nursing assistants try to devise a plan of care for every patient. Couple the duration of time with broken hips, stitches, impatient relatives, loud retching, sexually transmitted infections, fainting, and two traumas, the time spent i UNC Hospital Main E.D. is hectic.

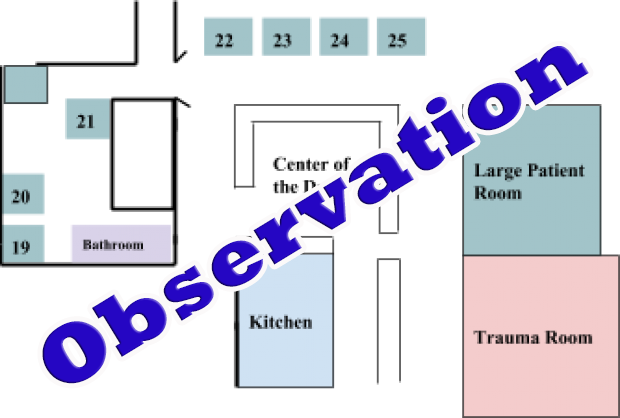

Initially, the Main E.D. seems disorganized. Medical equipment clutters floor space, with crutches in one isolated area tucked near the bathroom. However, the layout has a certain logic to it. Patients’ rooms line the walls and are separated off by curtains. An efficiently designed desk wraps around the center of the E.D. The desk resembles a kitchen island that extends, with two openings on either side that allow the staff to enter the area. The faculty congregate in the center of the desk area to record notes, confer about patients, and most notably, crowd around a computer to look at a patient’s X-ray or medical history.

The Emergency Department is a frenzy of people moving to and fro in maroon, black, or green scrubs, colors that correspond with their position. The woman in maroon scrubs, who pushes the meal delivery cart, is a nursing assistant. She and other maroon clad individuals check on patients and carry out requests. Nursing assistants lend a hand to weak patients when they have to walk around, and make sure dizzy patients do not crash to the hospital floor. The frenzy of the E.D. does not stop the momentum of care. The dark blur rushing around the E.D. is an emergency medicine doctor in black scrubs. They stitch up bloody gashes and flit from patient to patient asking about pain and symptoms.

The individual in navy blue scrubs that struggles to keep up with the E.D. is the scribe. They follow the emergency medicine doctor, typing down everything that is said between the doctor and the patient. Occasionally, medical doctors stop to hear input from surgical residents, identifiable by their sea foam green scrubs. Surgical residents scrutinize X-rays of patient’s brains, while turning and asking questions to the attending. Tonight, the attending is Dr. Pierce. She sits behind the desk, ready to answer any of the colored scrubs questions, acting as the resounding voice of the E.D.

Even with an attending doctor, and a full team of amazing medical personnel, the Emergency Department wouldn’t run smoothly without its carefully crafted patient identification system. Above every curtained room are signs with large black numbers. These numbers designate not only the room number but the patient inside it. It’s a simple system but needed in the chaos that can be the E.D. The events of the shift can be laid out by the by patient number and the interactions that occurred within each section:

19

The Emergency Department is a cold place for the patients in thin gowns. 19 is covered from head to toe in a peach blanket provided by the hospital. His head peeks out from the top. 19 is in an area that branches off from the main room of the E.D. He lays sequestered at the end of the area across from the bathroom and a pile of medical supplies. Susan, an emergency medicine doctor, does what she will do with every patient, first takes out her stethoscope and listens to the heart and lungs. Luke, the scribe, documents everything. 19 is quiet and has shortness of breath. Many of his questions are lost in the air and Susan has to lean in to hear a question he asks. She tells him he’ll be there for a while because of all the tests that have to be done.

19’s concern is echoed by other people in the Emergency Department. A woman and her sick mother, known as 23, had arrived to the E.D. in the afternoon and were still there after twelve hours. “It’s too long,” 23’s daughter gripes, “Someone has to get a move on.”

After checking in with 19, Susan leaves the branched off room and returns to the desk area. She darts to the computer at the attending physician’s chair, an action she does often to check patient’s history and see notes. Susan turns to Dr. Pierce for advice about how to proceed with care. She runs some questions by Dr. Pierce and mentions new information provided by the patient. “The fall was two or three weeks ago,” she tells Dr. Pierce about a man who fell during hospice care. Contradictory to the records that stated the fall was two or three days ago. After dropping by Dr. Pierce, Susan proceeds to her next patient.

24

Like 19, 24 is covered with blankets to provide extra warmth. She has swollen feet and shortness of breath. The stethoscope is pulled out once more, and 24’s son helps her lean forward has Susan checks her lungs.

An X-ray of 24 shows that her heart is larger than it should be. A normal sized heart is half the width of the chest on an X-ray. 24’s heart had expanded past that size, and looked like a large white mass in the X-ray film.

Suddenly, a scream rings out among the E.D. interrupting Susan’s concerns about 24’s heart. The cries come from a woman being rolled in on a stretcher.

22

22’s screams could be heard all over the E.D. Her right leg is crunched up and she cannot straighten it. “Can I cut off your pants?” Dr. Pierce asks. 22 took a tumble down some steps. Dr. Pierce elaborates that she needs an X-ray, but the metal zipper on her pants could impede the machine. 22 agrees. Two nurses in light blue take care of her pants while a woman in maroon rolls her out for her X-ray. Dr. Pierce is back sitting behind her desk when 22 rolls by and speaks to a surgical medical student, Alex, in seafoam green. Dr. Pierce asks him what 22 wanted:

“She wanted to know if she can get any more pain meds after the first.”

“No,” Dr. Pierce responds.

Three nurses share pumpkin spice popcorn as they work.

16

“Dr. Pierce, room 16 is up and walking,” a nursing assistant says while passing by the desk. A woman, presumably 16, follows after her. 16 has to be mobile in order to be cleared to go home.

A lull descends upon the E.D., but Cathy, a medical doctor, and Dr. Pierce refuse to admit it. “We never say that word,” says Dr. Pierce. “It starts with a q.” They refuse to utter the word “quiet” saying they cringe when a visitor says “it has gotten very q or it is q.” Regardless, there are no major incidents. Luke takes a break from his computer to fetch Dr. Pierce, Cathy, and Susan Starbucks from the cafeteria upstairs.

Alex returns from 22’s X-ray.

“She has a nice broken hip,” he concludes. People say broken hip but it is actually a broken femur. The hip is a joint. Dr. Pierce reconsiders her previous decision not to give 22 more pain medication.

Meanwhile, Susan attends to a gash on a man’s forehead. The injury is above his eyebrow, and has created a skin flap. Susan and others refer to his injury as a flap. The man, Fred, works in construction. “A piece of vinyl siding fell; instead of cutting, it bunched up. Everyone keeps calling it a flap,” he says. Susan stitches up the flap easily, but for now, one eyebrow is a little higher than the other.

Luke returns, refreshments are delivered, and he eats a chicken sandwich at his station.

21

A man retches and groans loudly interrupting the previous “q –ness”. As if the lull never occurred, Dr. Pierce, Susan, and Alex are recalling information about the patient. Before he is even rolled behind a curtain, they recount that he has been admitted to their department many times. They know he has pancreatitis, and they see from his records that he has a strained throat from retching.

“He is very anxious,” Susan tells Dr. Pierce. 21’s pain came on suddenly that day at 2 p.m. 21’s retching and coughing is heard in neighboring patient’s areas. A young woman who is there for sexually transmitted infection testing glances worriedly in the direction of 21’s curtain. She holds her stomach; her phone is already hooked onto a charger above the hospital bed. Susan sits on the bed with the young woman and talks to her quietly about the tests they are going to run.

Later, 16 departs with a grey plastic Kohl’s bag, and a discussion about 19 takes place between Susan and Dr. Pierce.

“Malnourished and dehydrated, he says he eats a little bit,” Susan reports.

“Do you get the feeling he’s trying to end things?” Dr. Pierce asks.

“Maybe. Passively not purposefully,” Susan responds.

Mental health plays a large part in the E.D. A psychologist is called down to attend to another patient, 25, whose wife is worried about his depression. Chronic pain can wear on the mind as well as the body. Dr. Pierce notes about one patient who has multiple sclerosis: “He urinates and defecates on himself and fails to clean himself up.”

The E.D. falls back into a calm. 21 falls asleep. After seeing 23’s daughter, the one worried about treatment wait time, Dr. Pierce on the phone to see if there is a way to have her mother transported. “This patient has been here twelve hours and she’s irate. How can we get her sent to Hillsboro?”

Trauma

The staff springs into action. A woman has fainted and has severe vaginal bleeding. The staff fears it may be an ectopic pregnancy. In these situations, the growing fetus lodges in a woman’s narrow fallopian tube instead of the uterus. Eventually the fallopian tube cannot withstand the pressure. Dr. Pierce speculates that the patient has a ruptured fallopian tube and she will need to be in surgery before the end of the night.

An ambulance light flashes red and yellow against the far side of the E.D. where sliding doors open for ambulances.

“Three traumas are coming in in the next forty minutes,” a woman with a mask, a protective red vest, and a floaty tissue paper like shirt announces suddenly. A large room is prepared to receive traumas. It is split down the middle for the first two traumas coming in. On the right side of the room, nurses, surgeons, and doctors crowd around as a man yells the symptoms and circumstances around the injury. A fifteen-month old baby fell off a coach and has a head bleed. The area on the left is for a man who got into a car accident involving a tree.

“Our pediatric patient is being offloaded,” a man yelled.

The staff immediately gets to work. An X-ray shows the whole bottom half of the fifteen- month old. On the other side a man groans in pain. “Give me a deep breath,” a staff member asks the man. “Can you give me a deep breath sir?”

The traumas continue to arrive during a shift change. Susan, Alex, Cathy, Luke, and Dr. Pierce’s work for the day is done. But the hospital does not sleep, and another group of doctors are there for their long eight-hour shift.

They stand around the chaos calmly giving notes to the emergency medicine doctor who is taking over. He scribbles notes next to the growing list of numbers. 22 is scheduled for hip replacement surgery tomorrow amongst a number of patients who need medical services.

UNC Hospital’s Main E.D. has its periods of calm and chaos. Sometimes patients will only need stitches, other times they will faint suddenly or need surgery. The dependable staff of emergency medicine doctors, nursing assistants, and surgical residents remain consistent. The earlier staff start to leave. Luke the scribe departs. Dr. Pierce heads out the same sliding doors the traumas came through. They will be back in the morning. Until then, the traumas will be there waiting.

Sources

Ectopic pregnancy. (n.d.). Healthy WA Health information for Western Australians. Retrieved from https://healthywa.wa.gov.au/Articles/A_E/Ectopic-pregnancy