Allusions as Web-Building Vehicles in V for Vendetta

Abstract

Some works call out to readers with an invitation to play an active role in the construction of the text’s meaning. Following the insights of Roland Barthes, who deems such texts “writerly,” Evans, Foote, and McDonald demonstrate how allusions in the graphic novel V for Vendetta enact this writerly phenomenon. Particularly, the allusions in the text create a feedback loop. They bring extra-textual meanings into the story, illuminating the work’s characters and themes, as well as launch the reader out from the text, situating her within a network of cultural and historical references. This back and forth process accounts for the richness of the work and reveals the strengths of the graphic novel as a writerly medium.

It is impossible to deny that some books seem to have the mystical ability of inclusion, allowing us not just to realize the work’s essence, but to fundamentally craft and shape it. Roland Barthes highlights the ability of literary works to involve readers in the creation of rich networks of meaning. The most engaging of texts, texts that can be broadened enough to be interpreted or “re-written” in a different way, he deems writerly. As Barthes puts it, “the goal of a literary work is to make the reader no longer a consumer, but a producer of the text” (Barthes 4). A writerly text actively involves the reader in its creation, ensuring that the subject has opportunities to project him or herself in the text’s interpretation.

Barthes elaborates on the idea of writerly texts, emphasizing the role of the reader, suggesting that “the writerly text is ourselves writing” (Barthes 5), and introducing the idea of a text’s “plurality” of meanings. To interpret a text is to appreciate the work’s diversity of potential meanings. A writerly text is always connecting to new situations, new emotions, new personal histories and experiences as an infinite network of plural meanings never, in themselves, representing a whole of the text. Certain works seem so broad and powerfully applicable because they have an incredible web of connections to a diverse range of thoughts, events, and people. This web provides a helpful way of understanding literary allusions. As Pietro Pucci explains, allusions have an “ability to signify broadly and widely on a grid of cultural interchanges whose patterns, forms and outcomes are varied” (Pucci 6). Carmela Perri elaborates on this notion, explaining that allusions are special because they include both a “unique extension” (connotation) and “precise aspects” (denotation of the referent’s intention) (Perri 292). In this sense, allusions reach outside the text, creating webs, even as they bring materials back into the text through their external references.

The power of allusions to draw from external materials provides potential references through which authors bring additional meaning into their works. A crafty author is able to intentionally manipulate allusions to incite a deeper understanding of textual issues, characters, and themes. There is an abundance of examples where a deep understanding of the referential power of allusions is necessary for getting at the root essence of a work (Harris 1). In “Musical Allusions in the Works of James Joyce: Early Poetry Through Ulysses,” Zach Bowen describes how references to music reveal new insights about the characters of Ulysses. Bowen argues that “[Mozart’s Don Giovanni] is inextricably bound to the action of the book both thematically and in the mind of the protagonist, Leopold Bloom” (Bowen 4). In this case, allusions guide the reader towards new insights into Joyce’s character profiles in this notoriously difficult and writerly work.

On the other hand, allusions move readers outside of the text into a fluid web of pluralistic meanings. Claes Shaar describes this plurality afforded by allusions that transcends a rigid structure: “There . . . is the synecdochic type where intra-contexts do not similarly coincide along a vertical plane, but extend into the periphery, moving outwards, as it were, beyond the vertical boundaries outlined by the surface contexts” (Schaar 18). A reader will be able to recognize an allusion’s significance when “the reader turns her attention away from the language of the allusion in order to consider a panoply of potential meanings for it” (Pucci 42). Overall, as Barthes says, “in this ideal text, the networks are many and interact, without any one of them being able to surpass the rest; this text is a galaxy of signifiers; it has no beginning; it is reversible . . . the codes extend as far as the eye can reach, they are indeterminable” (Barthes 5).

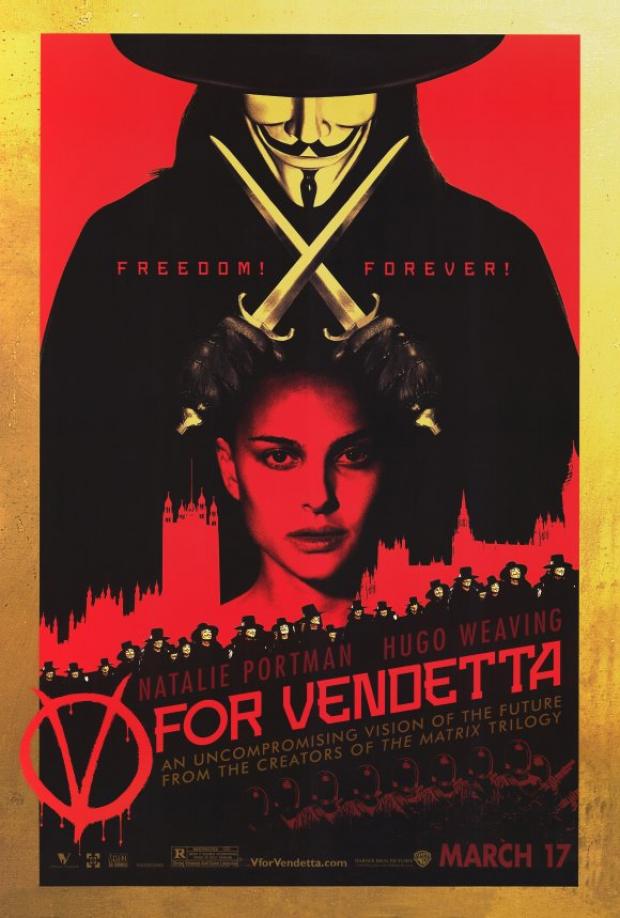

V for Vendetta, by Alan Moore and David Lloyd, clearly qualifies as such a writerly text. As a graphic novel, the work includes few words, and therefore allusions call out to the reader with a special urgency. In addition, the visual format creates a multitude of hiding spots for both textual and visual thematic clues. These allusions excite the intentional awareness of the reader, beckoning for his involvement in the text. Textual allusions generate an inward force, pulling in and incorporating other works to enhance the representation of the novel’s characters, add significance to plot developments, and highlight themes central to the text. At the same time, V for Vendetta uses its allusions to project outwards as Shaar describes, creating webs of reference that extend to historical events and culture. In this respect, the allusions in V for Vendetta operate as vehicles for simultaneously bringing other works in to the graphic novel and extending the novel out to create a lasting web of impressions. With this feedback loop, V for Vendetta extends its potential for meaning, inextricably linking itself to history, culture, and other literary works.In a Barthesian manner, this action expands the work’s plurality, making V for Vendetta not just a fun comic book, but a broad, writerly work that sucks the reader in and spits her back out towards new and exciting constellations of meaning.

An early allusion comes in the opening pages of V for Vendetta. In the scene, Evey, a main protagonist, approaches a shady man on an urban street and offers to prostitute herself in exchange for money. The man turns out to be a member of the Fingermen undercover police force (representative of the SS detectives of Hitler’s Nazi regime). Immediately, more evil Fingermen arrive on the scene with malicious intentions to rape and murder Evey. V, a masked hero, appears from the shadows, announcing in a dramatic voice “The multiplying villainies of nature do swarm upon him” (Moore 11). It is no coincidence that V’s first line in the entire novel is borrowed from Macbeth, one of William Shakespeare’s most famous dramas (Shakespeare 9). V continues to quote the famous tragedy as he billows smoke from his sleeve and carves up the evil henchmen of Britain’s totalitarian regime.

Fig. 1. V’s introduction (Moore 12).

During the attack, V announces “and fortune, on his damned quarrel, smiling, showed like a rebel’s whore . . . but all’s too weak for brave Macbeth . . . well he deserves that name” (Moore 12). In the context of the scene, the idea of “fortune” (i.e. fate) represented in Macbeth can connect both to the currently grim fate of England under the fascist regime and to V’s own eventual death at the end of the novel. V’s statement reflects his resistance to determinism and his refusal to let England continue under despotic governance. V describes himself as “disdaining fortune, with his brandished steel, which smoked with blood execution” (Moore 12) in order to hint at his plans to change England’s circumstance through violence. V’s elevated Shakespearean language compared to the thug’s “some kinda retard” slur juxtaposes the learned V and the confused, uncritical Fingermen. The allusion shows that V is a character that operates in a world of allusions. In addition, the Macbeth allusion also plays an aesthetic role in V’s entrance, setting a tone of excitement and grandiosity with elevated old-English language. One can’t help but internalize the gritty, bloody, and powerful Shakespearean tragedy in V for Vendetta’s opening as the allusion sheds light on the work’s characters and themes of fate, agency, and righteousness.

Fig. 2: Evey and V listen to “Dancing in the Street” (Moore 18).

While the Macbeth allusion links the powerful drama to V’s character, other V for Vendetta allusions act to project the work outward by forging historical connections. After their escape from the Fingermen, V takes Evey to his hidden, underground lair. V shows Evey his library and plays “Dancing in the Street” by the 60s band Martha and the Vandellas. Though glossed over in the dialogue, “Dancing in the Street” is a conceptually perfect fit for the pair’s discussion of the fascist government’s cultural holocaust. “Dancing in the street” is performed by African-American women jubilantly celebrating youth culture and free expression, two themes condemned by the book’s racist, fear mongering government. While there are scores of songs that would fit this description, “Dancing in the Street” is particularly appropriate to the world of V for Vendetta because of its historical associations with violent revolution.

The allusion also serves to move the reader away from the text and into a web of historical and cultural allusions. Starting in Detroit during their 1963 concert, Martha and the Vandellas’ hit song became a civil rights anthem for social change. In her book, Dancing in the Street: Motown and the Cultural Politics of Detroit, Suzanne Smith explains that the group had to cancel and abandon a series of concerts due to violence or possible violence from militant African-American nationalist leaders. Smith reports that, shortly after its release, a British journalist accused the song of being a call to riot. Though Martha repudiated these claims, “Dancing in the Street” became known as a touchstone song among the music produced in Detroit’s politically and racially charged environment (Smith). Here we see how allusions serve as vehicles, transporting meaning in and out of texts. The historical allusion illuminates the novel’s thematic condemnation of racism, fear, and oppression and the song shifts the tone of the work as it pulls in the fun, pumping rhythms of the music. At the same time, the allusion launches V for Vendetta into a historical period, connecting the work to a series of events associated with a time in history when civil rights were of paramount importance.

V for Vendetta shows how allusions can send readers on interpretive journeys as they engage a network of texts. Throughout the first half of the novel, Evey hides from the world in V’s lair to avoid the danger associated with V’s efforts to combat the English fascist regime. Moore sets a scene with V sitting next to Evey’s sleeping frame as soft hues of yellow light contrast against the black shadows of a child’s bedroom. V reads to Evey from The Faraway Tree, one of a series of children’s books written from 1939-1951 by Enid Blyton, a famous British writer (Rudder 10; Hunt).

Fig. 3. Evey falls asleep to V’s reading of The Faraway Tree (Moore 68).

One of the more subtle themes of The Faraway Tree involves the idea of change. The Faraway Tree is always branching out and changing, so the children return to a different magical land every time they climb it (Briggs et al). V reads, “It’s time we went back to the Faraway Tree. This land will soon be moving on—and as nice as it is, we don’t want to live here forever” (Moore 68). Here a reader’s ability to interpret this extra-textual reference is called into play. The Faraway Tree symbolizes adapting to changing times and growing up, something that illuminates Evey’s branching out in depth and substance as a character. This branching nature of the Faraway Tree also connects to the essence of V for Vendetta as a text that fundamentally constructs connections towards new pluralities of meaning and interpretation.

We can see the importance of recognizing the theme of change and maturation as The Faraway Tree reference reappears throughout the novel. Later in the book, V blindfolds the confused Evey, ordering her to follow him from the comfort of his lair to the outside world. Evey’s eyes are uncovered and she finds herself alone on a deserted street. V stands with his back facing Evey and cites the same quote from The Faraway Tree, eventually ending the passage with a dramatic “I’m not your father Evey. Your father is dead” (Moore 99-100). Evey, horrified, grabs V only to find that the image of V talking to her is really an elaborate costume and tape-recorder. The frame pans out to show Evey in the middle of a desolate, lonely scene.

Fig. 4. Evey alone with a phantom V (Moore 99).

Here a resonance between the two texts is established as the scene marks a major turning point for Evey. Evey is thrust from V’s sheltered protection out into the real world, starting a progression toward maturity that leads to her enlightenment. The timing also marks the beginning of the last time V calls her Evey; in subsequent scenes, she is known as “Eve,” yet another allusion highlighting her changing identity. The Faraway Tree represents movement away from childhood innocence, dependence, and naiveté. Again, we see meaning transported both away from and into the text as the allusion links Evey with a web of alternate texts and sets the stage for the novel’s protagonist spotlight to shift from V to Eve.

Many of the allusions in V for Vendetta create back and forth movements of intertextual meaning. But not all of these exchanges occur between literary texts. There are a number of pervasive symbols that transport meaning continually throughout the novel. V leaves a rose called the Violet Carson with every one of his victims. This rose is a real flower species named after a famous British actress known for playing a beloved character on the soap opera Coronation Street from 1960 to 1980 (“Ena Sharples”). Violet Carson plays the role of Ena Sharples in Coronation Street, a key member of the community and the self-proclaimed moral voice. Referencing this symbol of virtue, the rose attempts to embue V’s violent murders with a sense of higher purpose and moral justification, showcasing the tender, symbolic nature of V. The fact that V leaves these moral symbols behind for the murdered (as well as the investigators) represents V’s ethical justification of violence for higher purposes.

Fig. 5. V’s Violet Carson Rose (Moore 24).

In V for Vendetta, V is represented by a V framed in a circle. The symbol, while pervasive in the graphic novel’s frames, is never explicitly mentioned in the text. The V symbol is extremely similar to the symbol for anarchy. (See the ten second animation in Fig. 8 below.) The variation of the anarchist symbol illuminates the role V takes against the fascist British government. Historically, the allusion represents Alan Moore’s disillusionment with the English government in the 1980s under Margaret Thatcher. Moore explains, “well I suppose I first got involved in radical politics as a matter of course . . . I suppose that the overall consensus political standpoint was probably an anarchist one” (“Authors on Anarchism” 1). The anarchy allusion is unique because, unlike the other instances, it functions solely as a visual aid never explicitly mentioned in text. In this respect, the image takes advantage of the graphic niche created by the medium of V for Vendetta. Overall, the allusion functions to bring political and ethical philosophies into the text in a very subtle manner, also projecting V’s character into the contemporary anarchist movement.

Fig. 6. V’s symbol becomes the Anarchist Symbol (http://christiananarchyblog.files.wordpress.com/2008/11/anarchy-symbol1.jpg).

Perhaps the most pervasive allusion in the novel appears in V’s costume, a historical reference to the seventeenth century British anarchist, Guy Fawkes. Guy Fawkes is famous for the failed “gunpowder plot,” an effort to blow up England’s Parliament on November 5, 1605 (Bourdreaux 2). V dresses as Guy Fawkes to proclaim his similar intentions of armed rebellion against London’s powerful fascist government. The underlying meaning behind the symbol is that a government should work for its people instead of combating its citizens’ public interests. The mask of Guy Fawkes symbolizes the ethical idea of rebellion, but its allusion transports us into a meta-ethical network of issues related to government, authority, and human agency. Thomas Jefferson once said “When governments fear the people, there is liberty. When the people fear the government, there is tyranny” (“Spurious Thomas Jefferson Quotations”). The allusion to Fawkes evokes a range of similar references, transporting the reader into history as she weighs the concerns related to acting in political situations. The amazing power that comes from this network of associations between V for Vendetta and Guy Fawks shows the ability of a reference to connect a work with not only a historical date, but also with a wealth of political and cultural concerns related to that date.

Fig. 7. V References Guy Fawkes’ Terrorism (Moore 14).

V for Vendetta excites the attention of the reader with its colorful imagery, witty dialogue, and broad themes. One of the more subtle indications of its depth, however, is its multitude of allusions. These allusions bring meaning into the text, illuminating characters and themes. The allusions also work in the opposite direction, reaching out of the text and creating links to history and culture. Scholars such as Barthes, Shaar, and Pucci would agree that these references create a dynamic web of connections to be explored by the reader. The reader can’t help but get trapped in the vivid imagery of Guy Fawkes, qualitatively imagine V’s Shakespearean characterization, or understand Evey’s branching growth from adolescence to adulthood. Enabled with allusions, the reader actively both explores V for Vendetta’s internal collections of characters and themes and uses the text as a departure point for a journey into a buzzing web of associations.

Sources

“Authors on Anarchism—An Interview with Alan Moore.” Infoshop News. 17 Aug. 2007. Web.

Barthes, Roland. S/Z: an Essay. New York: Hill and Wang, 1974. Print.

Boudreaux, Madelyn. “An Annotation of Literary, Historic, and Artistic References in Alan Moore’s Graphic Novel, V For Vendetta.” Enjolrasworld, 27 Apr. 1994. Web.

Bowen, Zach. Musical Allusions in the Works of James Joyce: Early Poetry Through Ulysses. Albany: State University of New York Press, 1974. Print.

Briggs, Julia, Dennis Butts, and Mathew Orville Grenby. Popular Children’s Literature in Britain. Hampshire: Ashgate Limited, 2008. Print.

“Ena Sharples.” Wikia Entertainment. Web. <http://coronationstreet.wikia.com/wiki/Ena_Sharples>

Harris, William. “The Thematic Importance of Skelton’s Allusion to Horace in Magnyfycence.” Studies in English Literature 1500-1900 3.1 (1963): 9-18. Print.

Hunt, Peter. “Enid Blyton.” British children’s writers 1914-1960. Eds. Gary Schmidt and Donald Hettinga. Detroit: Gale Research, 1996. 50-71. Print.

Moore, Alan and David Lloyd. V for Vendetta. New York: DC Comics, 2005. Print.

Perri, Carmela. “On Alluding.” Poetics 7.3 (1978): 289-307. Print

Pucci, Joseph Michael. The Full-knowing Reader: Allusion and the Power of the Reader in the Western Literary Tradition. New Haven, Conn.: Yale UP, 1998. Print.

Rudder, Randy. “World’s Most Prolific Writers.” The Writer 118.3 (2005): 10. Print.

Schaar, Claes. “’The Full Voic’d Quire Below’: Vertical Context Systems in Paradise Lost” Lund Studies in English 60 (1982).

Shakespeare, William. Macbeth. Ed. Horace Furness. New York, N.Y.: Dover Publications, 1963. Print.

Smith, Suzanne E. Dancing in the Street : Motown and the Cultural Politics of Detroit. Cambridge: Harvard UP, 2000. Print.

“Spurious Thomas Jefferson Quotations.” The Jefferson Encyclopedia. 15 Dec. 2009. Web.