Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response as a Treatment for Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder

What do clips of Bob Ross painting and the repetitive snipping noises of the hairdresser’s scissors have in common? For most people, these would appear to be two completely random and unrelated concepts. However, for a select portion of the population, these situations can be linked together by the tingling sensation they stimulate in the body. Those who have encountered such a feeling may experience a phenomenon known as Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR). ASMR is immensely understudied, which can be attributed primarily to its novelty, as the term was only first officially coined in 2010 (Mervosh, “A.S.M.R. Videos”). Some of the few studies that have been conducted suggest that ASMR can provide benefits to mental health, sleep quality, and levels of stress (Barratt and Davis 5-11). Other studies insinuate that only a small percentage of the population can experience ASMR (Poerio et al.). It is currently unknown which groups in particular possess this ability, but the remedial benefits of ASMR seem to parallel many of the symptoms commonly associated with Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder (ADHD). The aim of this research is to explore both the viability and imperative of ASMR to act as a treatment option for individuals with ADHD.

ASMR has proven difficult for scientists to define in concise terms because it is such a complex phenomenon. The Department of Psychology at Swansea University in the United Kingdom loosely defines it as “a combination of positive feelings, relaxation and a distinct, static-like tingling sensation on the skin. This sensation typically originates on the scalp in response to a trigger, travelling down the spine, and can spread to the back, arms and legs as intensity increases.” There is a wide variety of these so-called “triggers” that are believed to stimulate ASMR; some typical examples include whispering sounds, words of affirmation, tapping noises, repetitive hand movements, roleplay situations, and socially intimate acts like hair brushing or the applying makeup (Barratt and Davis 6). The effectiveness of each trigger type can vary tremendously and is typically dependent on personal preferences.

While it is possible for ASMR to occur spontaneously in everyday life situations, these instances are in the minority. ASMR more frequently results from watching videos on social media platforms such as Reddit, Instagram, YouTube, and Tiktok, a network known as the “Whisper Community.” Here, content creators intentionally perform triggers for their viewers in hopes of stimulating ASMR and providing an outlet for those who are stressed, anxious, depressed, or simply in need of a friendly face. Viewers have shared continued gratitude towards videos like these. For example, on a video by content creator Sarah Lavender, one user writes, “it’s the combination of your soft spoken voice and the triggers in your video that makes all your videos super relaxing to listen to.” Another explains that “I was just having a horrible anxiety attack and couldn’t breath and your video forced me to focus on my breathing and re center” (Lavender, “ASMR for 1 HOUR”). These comments of approval are commonly found across various other social media videos and platforms, making it clear that ASMR holds a genuinely beneficial purpose and is not a bizarre internet sensation that will fade in the coming years.

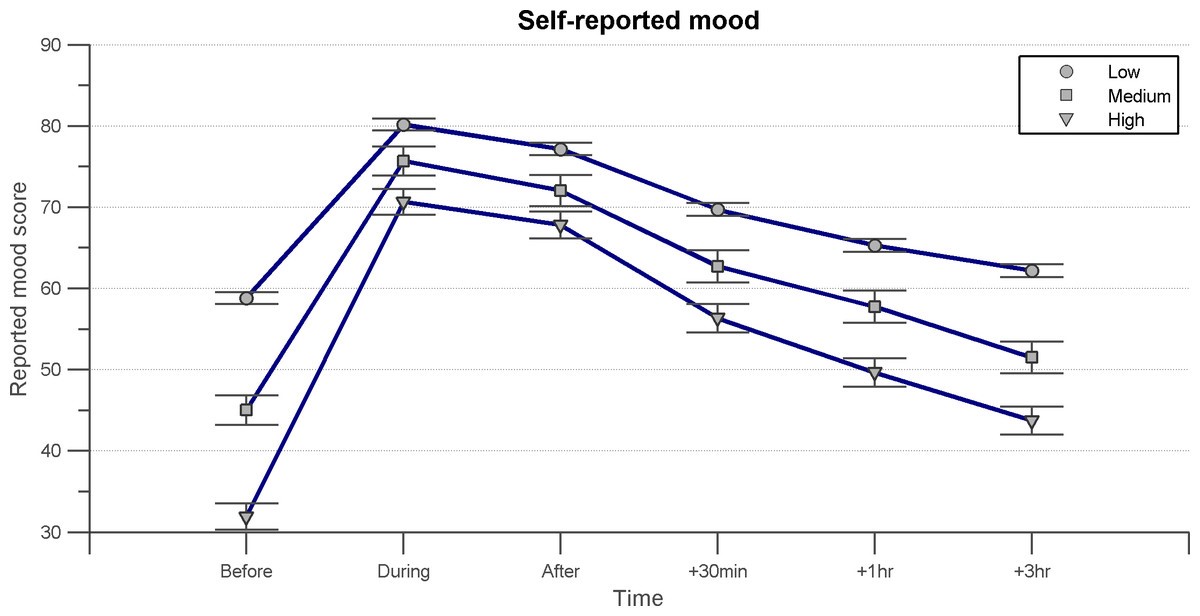

When strung together, these comments appear to tell a convincing story about the therapeutic potential of ASMR. To display these benefits more clearly, a formal study was conducted in 2015 at Swansea University in the United Kingdom. The researchers used a Likert scale to measure the degree to which their participants agreed with certain statements. They found that 98% of individuals agreed that they sought out ASMR for relaxation, 82% to help them sleep, and 70% to deal with stress. Furthermore, 69% of participants who scored moderate to severe on the Beck Depression Index (BDI) agreed that they sought out ASMR to lessen their symptoms of depression. Finally, as seen in Figure 1, ASMR vastly improved the reported mood scores for all levels on the BDI during ASMR exposure and for an extended period of time after (Barratt and Davis 5, 7-9).

Figure 1: Barratt, Emma and Davis, Nick. BDI Graph. Self-reported mood. 2015. Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR): a flow-like mental state. https://peerj.com/articles/851/.

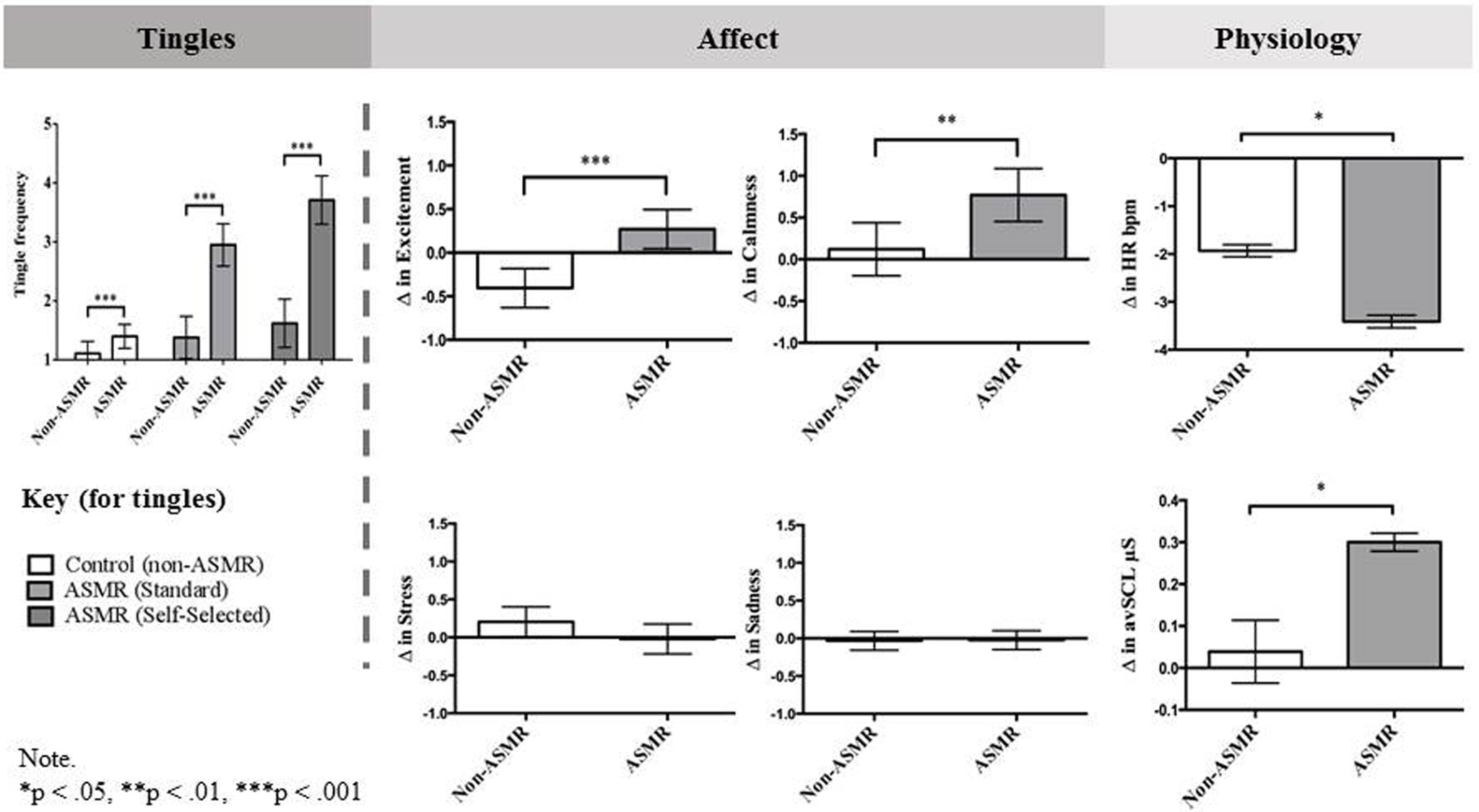

Another study at the University of Sheffield in the United Kingdom discovered in 2018 that ASMR can reduce heart rate and increase skin conductance levels, both of which are common outcomes of mindfulness-based interventions for anxiety. Furthermore, the participants of the study self-reported increases in excitement and calmness and decreases in stress and sadness (Poerio et al. 11-13). Figure 2 displays the graphical representation of these results.

Fig. 2. Poerio et al. The differences between ASMR groups on self-reported tingles and changes in affect and physiology after watching ASMR inducing videos, Summary of Results. 2018. More than a feel: Autonomous sensory meridian response (ASMR) is characterized by reliable physiology after watching ASMR inducing videos. https://journals.plos.org/plosone/article?id=10.1371/journal.pone.0196645.

Despite most of the evidence from these two studies being anecdotal, one can still soundly conclude from the data that ASMR promotes relaxation, improves sleep quality, and lessens the impacts of mental health conditions.

Analysis of these studies may beg the question: where does ADHD come into all of this? ADHD is a neurodevelopmental disorder that often begins in childhood and persists into adulthood. The most common symptoms of the disorder include difficulty sustaining attention and mental effort, forgetfulness, fidgeting, excessive talking, restlessness, and insomnia. ADHD also carries a high rate of comorbid psychiatric problems. What this means is that individuals with ADHD are likely to simultaneously present with other conditions such as oppositional defiant disorder, mood and anxiety disorders, and substance use disorders. Untreated ADHD can result in a multitude of negative consequences throughout one’s life including “academic and occupational underachievement, delinquency, motor vehicle safety, and difficulties with personal relationships” (Wilens and Spencer). Problems that ASMR is known to combat (e.g., anxiety, depression, insomnia, and restlessness) are problems frequently associated with ADHD. If it can be proven that individuals with ADHD are predisposed to experience ASMR, then this research can serve as a major breakthrough in finding new treatment options for ADHD.

To begin to prove this, it is crucial to understand the neural substrates that cause ASMR. One study conducted in 2019 compared the images produced through functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) in people who self-reported experiencing ASMR and those who did not. The researchers took images while the participants’ brains were in the resting state. They focused their imaging on the functional connectivity of resting-state networks. In other words, they looked to measure the correlation of the activity of different groups of neurons. The fMRI study revealed that individuals who experience ASMR exhibited reduced or atypical functional connectivity in the salience, visual, default mode, central executive, and sensorimotor networks (Smith et al. 508-518). Similarly, individuals with ADHD show reduced functional connectivity across many resting-state networks, particularly in the default mode network, which is linked to distractibility (Konrad and Eickhoff 904-916). These findings suggest that the ASMR brain shares similarities with the ADHD brain, and they allude to the fact that individuals with ADHD may be able to experience ASMR.

Another trait connecting individuals with ADHD and ASMR is sensory sensitivity. In a study from 2022, researchers speculated that “heightened sensory sensitivity to external cues [involved] greater salience to ASMR triggers.” They further proposed that “enhanced interoceptive awareness [involved] the translation of sensory stimuli to stronger internal emotional responses” (Poerio et al.). Hypersensitivity is a trait that is also common in individuals with ADHD due to alterations in neural networks, further bringing this group into the ASMR conversation (Ghanizadeh 91). However, the idea of sensory sensitivity raises a bit of a paradox. For individuals with extreme hypersensitivity, ASMR might trigger misophonia, “a condition where patients experience a negative emotional reaction and dislike (e.g., anxiety, agitation, and annoyance) to specific sounds (e.g., ballpoint pen clicking (repeatedly), tapping, typing, chewing, breathing, swallowing, tapping foot, etc.)” (Palumbo et al. 953). Misophonia frequently manifests in individuals with other pre-existing forms of neurodivergence, such as Autism Spectrum Disorder and ADHD (Galante and Alam 3). For others, though, being sensitive to stimuli allows sensory activities to foster relaxation and increase focus levels. This paradox must be further studied before claiming that all individuals with ADHD will benefit from ASMR, and it may serve as a limitation to the viability of ASMR as a treatment option.

The connection between ADHD and ASMR has a practical imperative. Currently, the typical treatment option for ADHD is medication, with the most common being the stimulant Adderall. There are two different types of stimulants: immediate-release and extended-release. Immediate-release stimulants often result in a rebound effect or a major drop in energy once they wear off. Extended-release stimulants tend to take longer to kick into the system and are aimed at providing relief throughout the day as opposed to alleviating sudden attacks of restlessness or anxiety. These stimulants can have short-term adverse effects including stomach aches, nervousness, a loss of appetite, and trouble sleeping. Furthermore, the cost of ADHD medication, which is frequently combined with the cost of therapy and private schooling, can be immense (Wilens and Spencer). Researchers must explore a new treatment option that provides free, immediate, painless relief to individuals with ADHD; perhaps ASMR can act as this alternative.

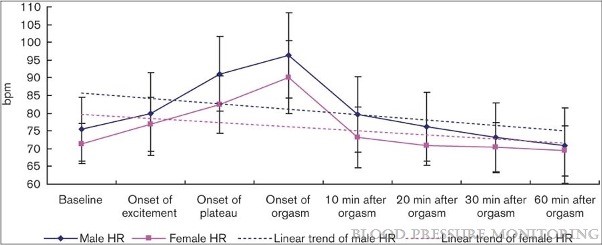

Although this research is important for suggesting a new treatment option for ADHD, it also emphasizes the validity of ASMR. Many people who do not experience the phenomenon themselves have criticized ASMR, claiming that it has a sexual basis. This stems from the fact that the industry is overwhelmingly female, with many videos on social media featuring women who are young and conventionally attractive. According to social psychologist Asia Eaton, ‘Our stereotype about women who are giving care and friendliness in a gentle, intimate way is linked with our image of women being sexual.” However, “despite these popular beliefs, experts claim that ASMR does not have a sexual basis” (Mervosh, “A.S.M.R. Videos”). A 2008 study found that heart rate tends to increase in healthy adults as a sexual response, with an average increase of approximately 20 beats per minute in both men and women (Xue-Rui et al. 213). Below, Figure 3 represents this data:

Fig. 3. Xue-Rui et al. Change of heart rate (HR) during sexual activity in healthy adults. 2008. Changes of blood pressure and heart rate during sexual activity in healthy adults. https://journals.lww.com/bpmonitoring/Abstract/2008/08000/Changes_of_blood_ pressure_and_heart_rate_during.5.aspx.

The Poerio study from 2018 found that heart rate decreased slightly in participants upon exposure to ASMR (Poerio et al. 11-13). The contrasting results from these two studies discredit the public’s negative perception of ASMR and solidify the fact that ASMR is unassociated with sexual release. Only once people in society overcome their prejudices and recognize the validity of ASMR will its full therapeutic potential be realized.

ASMR provides mental health benefits, relaxation, and better sleep quality to those who experience it. Due to reduced and atypical functional connectivity in the resting-state networks of their brains and heightened sensory sensitivity, it can be suggested that individuals with ADHD will experience ASMR at a higher frequency and intensity than neurotupical individuals. It is important to note that this hypothesis is far from black and white. Certain neurodivergent individuals may not be able to experience ASMR, while some neurotypical individuals may be able to. Researchers must conduct new experiments and studies to obtain the answers to important questions in this emerging field. For example, it would be interesting to discover whether the ability to experience ASMR is attained at birth or if certain actions can be taken to increase the chances of being able to experience ASMR. For now, neurodivergence seems to be a reasonable indicator that a person is affected by ASMR.

References

Barratt, Emma L., and Nick J. Davis. “Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR): A Flow-like Mental State.” PeerJ Life & Environment, vol. 3, 26 Mar. 2015, https://doi.org/10.7717/peerj.851.

Galante, Ariana, and Nafees Alam. “Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response as an Intervention to Autism Spectrum Disorder.” Psychology and Behavioral Science International Journal, vol. 13, no. 2, 2019, https://doi.org/10.19080/PBSIJ.2019.13.555859.

Ghanizadeh, Ahmad. “Sensory Processing Problems in Children with ADHD, a Systematic Review.” Psychiatry Investigation, vol. 8, no. 2, 20 Nov. 2011, pp. 89-94, https://doi.org/10.4306/pi.2011.8.2.89.

Konrad, Kerstin, and Simon B. Eickhoff. “Is the ADHD Brain Wired Differently? A Review on Structural and Functional Connectivity in Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder.” Human Brain Mapping, vol. 31, no. 6, 3 May 2010, pp. 904–916, https://doi.org/10.1002/hbm.21058.

Lavender, Sarah. “ASMR for 1 HOUR | Slow & Relaxing Triggers to Fall Asleep to 🌙💤 (Low Light).” YouTube, 26 May 2022, www.youtube.com/watch?v=sycRZtLZzjo&t=1s.

Mervosh, Sarah. “A.S.M.R. Videos Give People the Tingles (No, Not That Way).” The New York Times, 7 Feb. 2019, www.nytimes.com/2019/02/07/style/asmr-definition-video-women.html?searchResultPosition=1.

Palumbo, Devon B., et al. “Misophonia and Potential Underlying Mechanisms: A Perspective.” Frontiers in Psychology, vol. 9, no. 29 June 2018, https://doi.org/10.3389/fpsyg.2018.00953.

Poerio, Giulia L., et al. “The Awesome as Well as the Awful: Heightened Sensory Sensitivity Predicts the Presence and Intensity of Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR).” Journal of Research in Personality, vol. 97, no. 24 Dec. 2021, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jrp.2021.104183.

Poerio, Giulia Lara, et al. “More than a Feeling: Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response (ASMR) Is Characterized by Reliable Changes in Affect and Physiology.” PLOS ONE, vol. 13, no. 6, 20 June 2018, https://doi.org/10.1371/journal.pone.0196645.

Smith, Stephen D., et al. “Atypical Functional Connectivity Associated with Autonomous Sensory Meridian Response: An Examination of Five Resting-State Networks.” Brain Connectivity, vol. 9, no. 6, 7 May 2019, https://doi.org/10.1089/brain.2018.0618.

Wilens, Timothy E., and Thomas J. Spencer. “Understanding Attention-Deficit/Hyperactivity Disorder from Childhood to Adulthood.” Postgraduate Medicine, vol. 122, no. 5, 13 Mar. 2015, pp. 97–109, https://doi.org/10.3810/pgm.2010.09.2206.

Xue-rui, Tan, et al. “Changes of Blood Pressure and Heart Rate during Sexual Activity in Healthy Adults.” Blood Pressure Monitoring, vol. 13, no. 4, Aug. 2008, pp. 211–217, https://doi.org/10.1097/mbp.0b013e3283057a71.