Universal Basic Income: A Healthcare Solution for Underserved North Carolinians?

In 2019, presidential candidate Andrew Yang boldly introduced his Freedom Dividend Act, a proposal that would provide every American over the age of 18 unconditional payments of $1,000 each month, totaling $12,000 per year (yang). His proposition was more than an attempt to grab headlines during a failing campaign. However, Yang’s Freedom Dividend was an economic proposal building on years of American attempts to institute a Universal Basic Income program (UBI). UBIs aim to relieve poverty, stimulate the economy, and fight off the growing consequences of automation. While Andrew Yang has largely dropped out of the news cycle following his loss in the 2020 primaries, the potential of a Universal Basic Income program remains worthy of discussion.

Andrew Yang was not the first person to introduce the idea of a UBI, even in the United States. Proposals for similar programs go back as far as the 1800s, when economist Henry George advocated for a “citizens dividend.” In the 1960s, Martin Luther King and the Black Panther Party both called for a guaranteed income, and in the 1970s, presidential candidate George McGovern called for a UBI (“Universal Basic Income…”). The proposal never gained much traction; opponents argued that guaranteed income would breed a lazy workforce and that the policy would be too expensive (Li). Instead, the United States government opted for Means Tested Welfare (MTW) programs to address issues like poverty and healthcare. Means Tested Welfare, like the Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP), Supplemental Security Income (SSI), and Medicaid are each separate programs which individuals must apply for to receive benefits. A UBI, on the other hand, aims to eliminate any uncertainty caused by bureaucracy and provide comprehensive support that is not contingent upon factors like income.

This paper aims to answer how the implementation of a government run Universal Basic Income program would affect access to healthcare for underserved communities in North Carolina. First, we must analyze current issues with the American Healthcare system and the compounding effects of the global pandemic, then examine existing UBI programs within and outside of the United States. Through this analysis, we conclude that UBI could make a positive difference in many people’s lives and improve health outcomes but should not be considered a holistic solution for fixing the systematic issues plaguing American Healthcare.

Currently, countless barriers stand in the way of Americans accessing healthcare. Nearly half of all American adults say they struggle to afford healthcare costs, and four out of ten say they have either delayed or gone without medical care due to the exorbitant costs. Problematically, issues accessing affordable healthcare disproportionately affect low-income groups, uninsured adults, and Black and Hispanic individuals (Keary and Montero). In North Carolina, accessing healthcare can be extremely difficult as over 11% of the population — approximately one million people — are uninsured. This figure also includes 142,000 children. Furthermore, census data indicates that the number of uninsured North Carolinians is rising (Logan).

Legislators have half-heartedly attempted to address issues of healthcare access over the years, but government run healthcare and welfare programs typically fall short of providing basic healthcare needs. After the Affordable Care Act was enacted, the number of uninsured dropped from more than 46.5 million in 2010 to fewer than 26.7 million in 2016, yet these coverage gains quickly eroded. Following 2016, “the uninsured rate for near-poor nonelderly individuals and those with incomes above 200% of poverty increased significantly” (Orgera and Tolbert). Means-tested welfare programs, while potentially beneficial in the short term, prove to be volatile and ineffective in solving long term issues. Current programs like Medicaid have certain barriers that prevent people from qualifying. North Carolina is a state without expanded Medicaid, which means that non-disabled, childless adults receive zero Medicaid benefits. Gaps in Medicaid coverage have serious consequences. An estimated 208,000 North Carolinians cannot obtain any public health insurance coverage, meaning they will likely face both worse healthcare access and poor health outcomes (Spencer et al.)

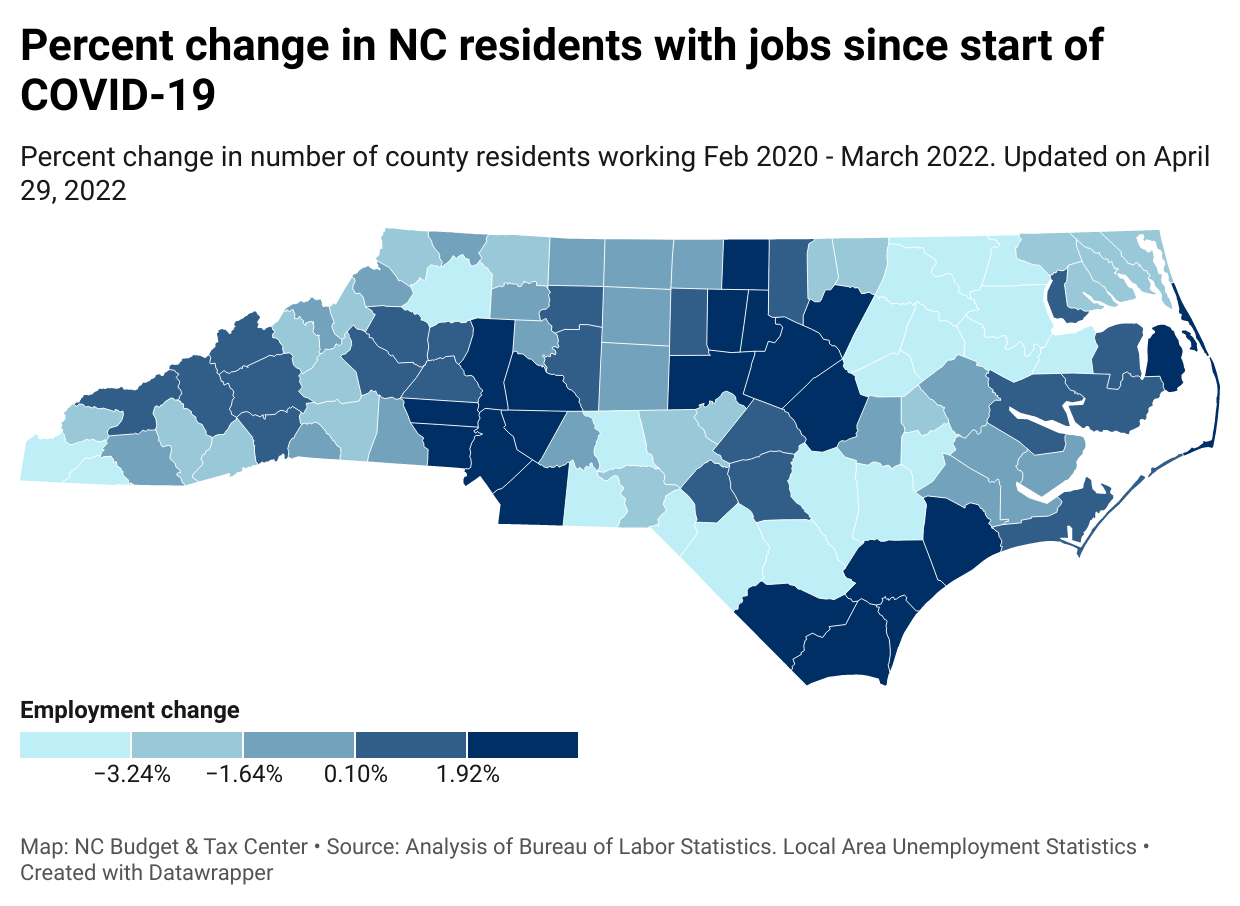

Unfortunately, this bleak picture only gets worse because of COVID-19. The Global Pandemic saw a large rise in unemployment as employers laid off millions of American workers. Between March and April 2020, approximately 500,000 North Carolinians lost their jobs (Levy). Even as the country has tried to build back, many areas of North Carolina have fallen behind. Nearly three quarters of North Carolina counties have fewer people working now than before the pandemic (McHugh). Figure 1 illustrates the post-pandemic trend in job growth: cities have regrown, but rural areas have stagnated.

Figure 1: McHugh, North Carolina Budget and Tax Center

While the state as a whole has seen job recovery, job growth is disproportionately in cities, leaving rural areas behind. Half of all Americans receive health insurance through employers, so by increasing unemployment, COVID reduced access to healthcare (“Employment-Based Health Insurance…”). Furthermore, much of the unemployment caused by COVID-19 was short term, and the short-term unemployed often face issues accessing both employer-sponsored and public benefits. A 2021 American Journal of Industrial Medicine study quantifies that “more than one-third of [the short-term unemployed] reported lacking health insurance; 41.4% did not have a personal provider; and 30.3% needed to see a doctor in the past year but could not because of cost” (Silver). Even if job losses were temporary, many were forced to forgo care due to a COVID-caused job loss.

The Pandemic applied pressure to an already fractured system which Universal Basic Income could help fix. A UBI has already been adopted in various ways across the globe, and direct cash transfer systems in other countries provide valuable insight into how individuals use the money they are given. For example, Brazil provides monthly direct cash payments to around 13.8 million families (Paiva et al.). Families can spend this in whatever way they see fit, and they spent an estimated 87% directly on food. This program effectively fights hunger for poor Brazilians and has been shown to increase food expenditure on natural, minimally processed, high calorie foods (Martins et al.). While the money is not going directly to healthcare for most Brazilian recipients, increasing spending on food is still key to improving health outcomes. A 2015 Health Affairs Journal study found that children in food insecure households are twice as likely to report having poor to fair health. Thus, reducing food insecurity corresponds with better health outcomes (Gunderson et al.).

UBI Pilot Programs are another valuable method of analyzing the effects of cash transfer welfare. In the 1970s, a town of around 10,000 in Manitoba Canada started an experimental program called MINCOME, where households received federally assured income for 5 years. In 2011, Economist Evelyn Forget analyzed health administration data in Manitoba during that period and found both health and social benefits. Relative to a comparison group without MINCOME, recipients saw fewer hospitalizations, fewer physician contacts, and fewer mental health diagnoses (Forget). Like in Brazil, there is a clear link between cash transfers and improved health.

Aside from food, having extra cash makes all aspects of receiving appropriate healthcare more possible. For example, there are transportation costs to physically get to a doctor. Lack of reliable transportation results in nearly 4 million Americans skipping out on healthcare visits each year (Wright). Workers also must worry over whether they are fiscally able to miss an hour or two of work to get treatment. If somebody cannot get time off work or a ride to the doctor, they will likely be forced to miss their doctor’s appointment. Having extra disposable income each month makes costs associated with simply getting into a medical facility more realistic. While UBI’s cash payments make these issues easier to handle, healthcare access still remains an issue. In each example of UBI type programs, health outcomes improved, but there was no evidence that the actual ability to see a healthcare provider changed. Since many North Carolinians have no health insurance, people would face extremely high out-of-pocket costs, with the per-day hospital cost averaging $2,883 in the United States (Milliken). Even for the insured, most proposed UBIs would not cover health insurance as the average amount spent on health insurance for a family in North Carolina is $2,130 (Guinan).

A two-year UBI pilot program in Stockton California clearly illustrates how a UBI cannot solve all the issues of healthcare access. The Stockton program was on a much smaller scale than the cash welfare in Brazil and the Manitoban program, but still showed similar effects: 125 individuals were chosen to receive $500 each month for two years, and after the two years, recipients were found to be healthier, showing less depression and anxiety and enhanced wellbeing, as well as less economic volatility. However, when the recipient’s spending was broken down into categories, only 3.28% was spent on “insurance” costs and 3.06% was spent on “medical” costs while 36.92% was spent on food (West et al.). While food is certainly not a bad expense, food expenditure in comparison to both health and insurance costs are important to note when considering public policy. In multiple instances, UBI payments have been shown to improve health outcomes, but almost solely due to improving households’ material conditions and not by making drug prices less daunting or insurance a more viable option.

Healthcare costs remain high for even those who are insured, so the United States would have to do more than just UBI to address the effects healthcare costs have on access. The average annual healthcare expenditure in the United States, accounting for the insured, is $12,530 per adult and $3,749 per child (“NHE Fact Sheet”). A family, assuming they pay the national averages in health expenditure, could not cover their healthcare costs with a Universal Basic Income at the proposed $12,000/year, even if the entire amount was spent on health payments. Surprise medical bills are a compounding factor: the average ER visit cost for someone uninsured was $1,220, meaning an uninsured person who ends up in the emergency room would not be able to cover the surprise bill with their basic income payment from that month (Dahlen). Even with more disposable incomes, people would still face the issue of skipping care due to high costs in a world with a UBI, leaving problems in accessing healthcare unresolved. Together with other social spending, however, a UBI may make a real difference. If a UBI were enacted alongside a single-payer nationalized healthcare system, similar to the United Kingdom’s National Health Service (NHS), cash payments may be able to effectively improve health outcomes. As seen in existing programs, the UBI payments could still improve health outcomes through better nutrition and less stress, while nationalized healthcare would ensure no cost to patients trying to seek medical care. By itself, a Universal Basic Income would likely function as a band-aid solution to address surface issues of living a healthy life, yet could be incredibly effective alongside other policies making healthcare accessible. A Universal Basic Income could help many struggling North Carolinians live a healthier life, but it should not be considered an effective solution to the systematic issues with American Healthcare and would be much more effective in conjunction with other policies and programs that aim to reduce healthcare costs.

Resources

Dahlen, Gretchen. “Emergency Room – Typical Average Cost of Hospital Ed Visit.” Consumer Health Ratings, 13 Oct. 2022. https://consumerhealthratings.com/healthcare_category/emergency-room-typical-average-cost-of-hospital-ed-visit/.

“Employment-Based Health Insurance U.S. Share 1987-2021.” Statista, 15 Sep. 2022. https://www.statista.com/statistics/323076/share-of-us-population-with-employer-health-insurance/.

Forget, Evelyn. “The Town with No Poverty: Using Health Administration Data to Revisit Outcomes of a Canadian Guaranteed Annual Income Field Experiment.” Collaborating Centre for Determinants of Health, 2011 https://nccdh.ca/resources/entry/the-town-with-no-poverty.

Guinan, Stephanie. “Best Cheap Health Insurance in North Carolina.” Value Penguin, 9 Feb. 2023. https://www.valuepenguin.com/best-cheap-health-insurance-north-carolina.

Gundersen, Craig, and James P Ziliak. “Food Insecurity and Health Outcomes.” Health Affairs Journal, vol. 31, no. 11, 1 Nov. 2015. https://doi.org/10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645

Harris, Logan. “U.S. Census Bureau Releases Data on Health Insurance Coverage in N.C.” North Carolina Justice Center, 16 Sep. 2020. https://www.ncjustice.org/u-s-census-bureau-releases-data-on-health-insurance-coverage- in-n-c/.

Kearney, Audrey, and Alex Montero. “Americans’ Challenges with Health Care Costs.” Kaiser Family Foundation, 14 Jul. 2022. https://www.kff.org/health-costs/issue-brief/americans-challenges-with-health-care-costs/

Levy, Joshua. “A Closer Look at NC’s Pandemic Job Losses.” North Carolina Department of Commerce, 13 Jan. 2021. https://www.commerce.nc.gov/blog/2021/01/13/closer-look-ncs-pandemic-job-losses.

Li, Fan. “Is Universal Basic Income the Key to Happiness in Asia?” Stanford Social Innovation Review, 12 Jul. 2021. https://doi.org/10.48558/P081-5V36.

Martins, Ana Paula Bortoletto, and Carlos Augusto Monteiro. “Impact of the Bolsa Família Program on Food Availability of Low-income Brazilian Families: A Quasi Experimental Study.” BMC Public Health, vol. 16, no.1, 19 Aug. 2016. https://www.doi.org/10.1186/s12889-016-3486-y

Maureen, Milliken. “Hospital and Surgery Costs: Paying for Medical Treatment.” Debt.org, 30 Mar. 2023. https://www.debt.org/medical/hospital-surgery-costs/#Hospital_Costs.

McHugh, Patrick. “Local Job Data: Nearly 75% of NC Counties Still Have Fewer People Working than Pre-Pandemic.” North Carolina Policy Watch, 3 Feb. 2022. https://pulse.ncpolicywatch.org/2022/02/03/local-job-data-nearly-75-of-nc-counties-still- have-fewer-people-working-than-pre-pandemic/#sthash.OC6SBxO7.dpbs.

McHugh, Patrick. “More Jobs in NC than before COVID, but Not Everyone is Recovering the Same.” North Carolina Budget and Tax Center, 29 Apr. 2022. https://ncbudget.org/more-jobs-in-nc-than-before-covid-but-not-everyone-is-recovering-t he-same/.

“NHE Fact Sheet.” Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services, 12 Aug. 2022. https://www.cms.gov/research-statistics-data-and-systems/statistics-trends-and-reports/nationalhealthexpenddata/nhe-fact-sheet#:~:text=Historical%20NHE%2C%202021%3A, 17%20percent%20of%20total%20NHE.

Orgera, Kendal, and Jennifer Tolbert. “Key Facts about the Uninsured Population.” Kaiser Family Foundation, 12 Nov. 2020. https://www.kff.org/uninsured/issue-brief/key-facts-about-the-uninsured-population/.

Paiva, Luis Enrique, Pedro H. G. Ferreira de Souza, Letícia Bartholo, and Sergei Soares. “Evitando a Pandemia da Pobraza: Possibilidades Para o Programa Bolsa Familia e Para o Cadastro Unico em Resposta a COVID-19.” The Institute of Applied Economic Research, Mar. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1590/0034-761220200243

Silver, Sharon R et al. “Employment status, unemployment duration, and health-related metrics among US adults of prime working age: Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System, 2018-2019.” American Journal of Industrial Medicine, vol. 65, no.1, 8 Nov. 2021. https://www.doi.10.1002/ajim.23308

Spencer, Jennifer C et al. “Health Status and Access to Care for the North Carolina Medicaid Gap Population.” North Carolina Medical Journal, vol. 80, no. 5, 14 Sep. 2019. https://www.doi.10.18043/ncm.80.5.269.

“Universal Basic Income: Key to Reducing Food Insecurity And Improving Health.” Center for Hunger Free Communities. 2021. https://drexel.edu/hunger-free-center/research/briefs-and-reports/universal-basic-income/.

West, Stacia, Amy Castro Baker, Suki Samra, and Erin Coltrera. “Preliminary Analysis: SEED’s First Year.” Stockton Economic Empowerment Demonstration. 2020. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/6039d612b17d055cac14070f/t /6050294a1212aa40fdaf773a/1615866187890/seed_preliminary+ analysis+seeds+first+year_final+report_individual+ pages+.pdf.

Wright, Ashley. “NEMT Cost of Care Study: How Does Transportation Impact Healthcare Spending?” MTM, Inc., 11 Jul. 2022. https://www.mtm-inc.net/nemt-cost-of-care-study-how-does-transportation-impact-health care-spending/.

Yang, Andrew. “Andrew Yang for President.” Yang2020. 2020. https://2020.yang2020.com/what-is-freedom-dividend-faq/.