Addressing Socioeconomic Inequality with a Wealth Tax

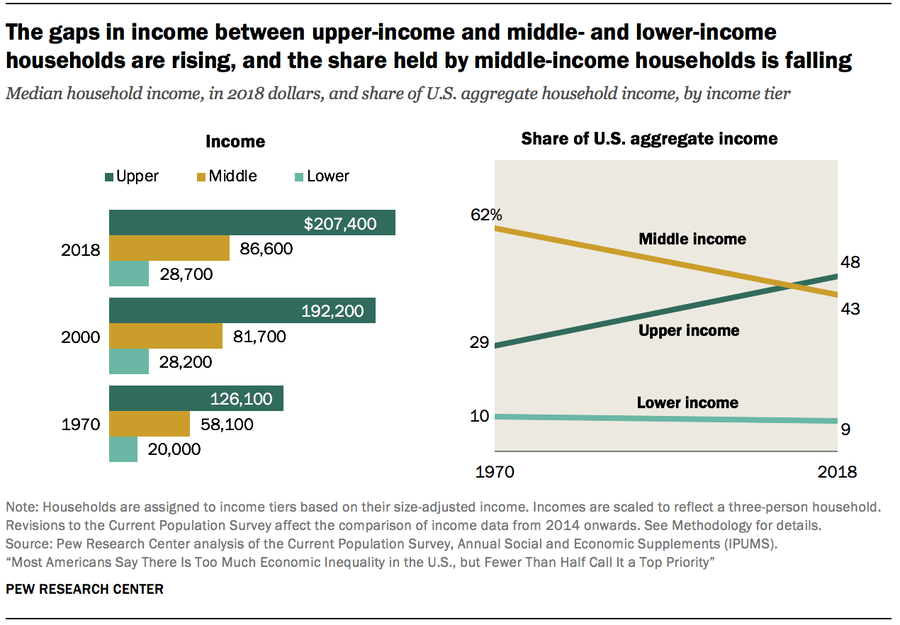

Wealth inequality has been rising at unprecedented rates in the United States. The Federal Reserve recently reports that the top 1% possess nearly one-third of all United States household wealth, compared to the 1.9% of household wealth that the bottom 50% have (“Distribution” 2019). Wealth is defined as the total net worth of an individual, which is calculated by subtracting their liabilities from the market value of all their owned assets. This encompasses a broad range of financial holdings, such as property, stocks, bonds, and other investments, as well as material possessions. Wealth is distinct from income, which refers to the money earned through employment, investments, or other sources over a specific period. The Pew Research Center highlights that the wealth disparity is intensifying, with a larger portion of the country’s total income being allocated to higher-income households, while the shares for middle- and lower-income households are decreasing (Horowitz et al. 2020). This is proven by the Gini Coefficient, a value between 0 and 1, which measures income or wealth inequality, with 0 signifying perfect equality and 1 denoting maximum inequality. The US Gini Coefficient rose from 0.462 in the 1990s to 0.481 in 2019, reflecting increased income inequality (Semega et al. 2022).

Figure 1: Horowitz et al.

Recent efforts to address this growing financial disparity have come from politicians, including former Democratic candidate Elizabeth, who propose a wealth tax. Economist Huaqun Li of Tax Foundation, a non-profit think tank, explains that wealth taxes are imposed on an “individual’s net wealth, or the market value of their total owned assets minus liabilities,” unlike income taxes in the status quo. This distinction is crucial, as a Forbes study found that income taxes on higher earners have historically been ineffective at targeting economic inequality in the United States (Dorfman 2017). For this reason, Reuven Avi-Yonah of The American Prospect concludes that “the income tax was adopted over a century ago because state property taxes could not reach intangible assets like stocks and bonds” but “today we have the means to tax the super-rich on these assets, and it is high time we did so, especially when faced with inequality that rivals the Gilded Age.” This essay will explore the history and politics behind wealth taxes and discuss their potential to be a solution to wealth inequality in the United States.

In America, the idea of taxing the rich has historically gained traction during times of economic disparity, with notable figures like President Franklin Delano Roosevelt playing a crucial role in transforming this idea into policy. The origins of this notion can be traced to the Gilded Age, when social reformers advocated for taxation methods that targeted the growing number of plutocrats and monopolists who ruled the economy. In the 19th century, economist Henry George proposed a “land tax” to deprive the wealthy of reaping rents from their ownership of real estate, but this idea soon lost relevance in political discussion due to constitutional constraints on federal property taxes (Mihm 2019). As an alternative, reformers considered an income tax, which, after a 14-year campaign, was finally levied in 1913 following the passage of the 16th Amendment (Walsh 2019). During Roosevelt’s presidency, the executive branch pursued a progressive and radical tax policy. In response to populist pressure, Roosevelt enacted the Revenue Act of 1935, which significantly increased tax rates and marked a departure from previous income tax policies. Roosevelt’s goal was to “break the taboo against going after the rich,” and his policies cemented the idea of taxing the rich into mainstream culture, making it a successful rhetorical tool for the Democratic Party (Mihm 2019). As wealth inequality currently reaches new heights, income taxes no longer serve their intended purpose of effectively taxing the rich. As reporter Ben Walsh explains, the income tax, initially intended to tax the fortunes of robber barons, now reaches far down the ladder in terms of who pays it. Nonetheless, the introduction of income tax in America established the foundation for progressive taxation and set the stage for future discussions on implementing a wealth tax.

Many politicians look towards Europe to replicate successful economic policy, but not in the case of wealth taxes. European nations initially popularized the idea of taxing an individual based on their wealth instead of their income. In 1990, there were twelve countries with a wealth tax in Europe, yet today there are only three remaining: Norway, Spain, and Switzerland (Rosalsky 2019). French economists Emmanuel Saez and Gabriel Zucman from the University of California, Berkeley explain that a primary reason for the failure of wealth taxes in Europe is mobility. Affluent taxpayers can either store their assets offshore or move to a different country without wealth taxes in the European Union (Saez and Zucman 2016). Joseph Zeballos-Roig from Business Insider explains that “France was the latest country to scrap its three-decades-old wealth tax back in 2017,” due to “the exodus of wealthy people leaving the country.” Researchers Jack Salmon and Veronique de Rugy from George Mason University quantify that “10,000 millionaires left France in 2015” due to the implementation of a wealth tax, casting doubt on the feasibility of a wealth tax in the United States.

Despite the issue, European failures stemmed from poor implementation, which the US (United States) can circumvent using well-designed wealth taxes. Zeballos-Roig explains that an American wealth tax would avoid European failure in two ways. First, the United States is not politically amalgamated with nearby countries the same way European nations are united by the European Union, meaning American citizens cannot freely move from nation to nation, unlike someone with a passport from the EU (Zeballos-Roig 2019). Second, Warren’s plan for wealth taxes includes a 40% “exit tax,” which is levied upon citizens with a net worth above $50 million if they decide to renounce their citizenship (Zeballos-Roig 2019). For these reasons, Zeballos-Roig concludes that Warren’s wealth taxes were designed “with Europe’s failures in mind.”

Looking past historical and political perspectives, the economic arguments for implementing a wealth tax in the United States are robust. Economists Stuart Adam and Helen Miller of the Institute for Fiscal Studies suggest that wealth serves as a more stable metric for taxation because it represents the ability to pay beyond income, spending, and inheritances. As a result, wealth taxes can assist in balancing wealth redistribution and work incentives, as well as reallocating capital to more efficient uses. Another reason wealth taxes uniquely benefit the state of the economy is by taxing savers. In other words, a wealth tax would disincentivize the accumulation of money, encouraging people to spend their disposable incomes and stimulating the economy (Adam and Miller 2021). According to Somin Park of the Washington Center for Equitable Growth, an economy effectively designed with a wealth tax has the potential to provide greater and more widespread economic well-being compared to an optimal capital income-tax economy. This is due to a substantial increase in consumption levels, driven by reduced labor income taxes and a decrease in inequality (Park 2019). Critics may contest the implementation of a wealth tax because the valuation of wealth and illiquid goods, assets which cannot be easily converted into a cash value, may be difficult. However, a fundamental part of establishing a functional wealth tax is through successfully determining the value of assets upon which the tax will be levied (“Economic” 2022). Wealth taxes can employ simple valuation methods, like those used by private firms for appraising or estimating market values of assets such as land and real estate, thus making the process of assessing and collecting taxes more efficient and transparent for both taxpayers and the government.

For a wealth tax to mitigate financial inequality in America, it must first surpass several political hurdles and be congressionally enacted. Conceptually, a wealth tax has public backing (Casselman and Tankersley 2019). Journalists Ben Casselman and Jim Tankersley of The New York Times report that “a majority of people support Democratic proposals to raise taxes on the wealthiest Americans. However, Casselman and Tankersley are quick to indicate that “polling support is by no means a guarantee that Americans would elect a tax-the-rich challenger to President Trump” since there are often huge disparities between poll results and political outcomes (Casselman and Tankersley 2019). Gallup polls spanning several decades have shown that voters believe that the wealthy are not taxed enough, but still end up electing presidents who lower those taxes (Gallup). An example of such a president would be Trump, who enacted a “$1.5 trillion tax cut that reduced the top marginal income tax rate” (Casselman and Tankersley 2019).

Regardless of whether wealth taxes are believed to mitigate inequality in the United States, it is up to the Supreme Court to decide if they are constitutional. From George Washington University, Jonathan Turley explains that the Constitution permits Congress to enforce taxes if they are “uniform throughout the United States” and “in proportion to the census or enumeration herein before directed to be taken.” This requirement may deem Warren’s wealth tax as unconstitutional since it would only apply to specific individuals unevenly distributed among states. Thus, it would end up being apportioned by state, meaning the super-rich in places such as Mississippi would have to “carry the whole tax for that state” compared to “their rich counterparts in New York or California,” which would shift away from Warren’s plan of taxing an individual’s net worth (Turley 2019). However, the future of a wealth tax’s political feasibility is bright. Calvin Johnston from the University of Texas at Austin concludes that wealth taxes may soon be regarded as constitutional since taxes such as income taxes remained in law despite intense legal battles.

Wealth inequality continues to grow, and wealth taxes aim to mitigate what income taxes could not. Despite historical struggles for taxes to pass the Supreme Court and Europe’s failures, modern plans for a wealth tax can avoid the pitfalls of Europe’s implementation and be legally accepted like income taxes were in 1913. There are many reasons rooted in fiscal analysis which suggest that wealth taxes may offer a solution to rising inequality by generating taxes on savers and asset valuation techniques that are comparable to current income tax models. Economists will corroborate that a wealth tax may resolve such issues. However, caution is necessary, as historians may be quick to point out that wealth taxes may soon meet the same fate as income taxes, extending deep into the American population and missing the target of eliminating the economic disparity in America. Thus, while a wealth tax may seem like the clear solution to address socioeconomic inequality, careful consideration must be given to its implementation and potential long-term consequences.

References

Adam, S., & Miller, H. (2021, October 25). The economic arguments for and against a wealth tax. Fiscal Studies, 42(3-4), 457–83. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-5890.12288.

Avi-Yonah, R. (2019, August 28). The shaky case against wealth taxation. The American Prospect. https://prospect.org/economy/shaky-case-wealth-taxation/

Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve System. (2019, December 23). Distribution of household wealth in the U.S. since 1989. https://www.federalreserve.gov/releases/z1/dataviz/dfa/distribute/chart/

Casselman, B., & Tankersley, J. (2019, February 19). Democrats want to tax the wealthy: Many voters agree. The New York Times. https://www.nytimes.com/2019/02/19/business/economy/wealth-tax-elizabeth-warren.html

Congressional Research Service. (2022, April 1). An economic perspective on wealth taxes. https://crsreports.congress.gov/product/pdf/IF/IF11823.

Dorfman, J. (2017, September 19). Higher taxes on the rich are not enough to stop inequality. Forbes. https://www.forbes.com/sites/jeffreydorfman/2017/09/19/higher-taxes-on-the-rich-are-not-enough-to-stop-inequality/?sh=72c976b95b96

Gallup Historical Trends. Taxes. Gallup. https://news.gallup.com/poll/1714/taxes.aspx

Horowitz, J. M., Igielnik, R., Kochhar, R. (2020, January 9). Trends in U.S. income and wealth inequality. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/social-trends/2020/01/09/trends-in-income-and-wealth-inequality/

Johnson, C. H. (2019, August 8). A wealth tax is constitutional. American Bar Association Tax Times, 38(4), 6–15. https://www.americanbar.org/groups/taxation/publications/abataxtimes_ home/19aug/19aug-pp-johnson-a-wealth-tax-is-constitutional/

Li, H. (2019, December 9). Comparing wealth taxation and income taxes. Tax Foundation. https://taxfoundation.org/comparing-wealth-taxes-and-income-taxes/#:~:text=Wealth%20taxes%20are%20levied%20on%20the%20 wealth%20stock%20on%20an,a%20high%2Drate%20income%20tax.

Mihm, S. (2019, January 29). Taxing the rich is an idea whose time has come — and gone. Bloomberg News. https://www.bloomberg.com/opinion/articles/2019-01-29/wealth-tax-plans-have-a-long-and-contentious-u-s-history#xj4y7vzkg

Park, S. (2019, October 10). Why a wealth tax in the United States might increase efficiency. Washington Center for Equitable Growth. https://equitablegrowth.org/why-a-wealth-tax-in-the-united-states-might-increase-efficiency/.

Rosalsky, G. (2019, February 26). If a wealth tax is such a good idea, why did Europe kill theirs? National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/sections/money/2019/02/26/698057356/if-a-wealth-tax-is-such-a-good-idea-why-did-europe-kill-theirs

Saez, E., & Zucman, G. (2016, February 16). Wealth inequality in the United States since 1913: Evidence from Capitalized Income Tax Data. The Quarterly Journal of Economics, 131(2), 519–78. https://doi.org/10.1093/qje/qjw004.

Salmon, J., & de Rugy, V. (2020, February). Revisiting the proposal for a wealth tax. Mercatus Center. https://www.mercatus.org/research/policy-briefs/revisiting-proposal-wealth-tax.

Semega, J., Kollar, M., Shrider, E., & Creamer, J. (2020, September 15). Income and poverty in the United States: 2019. United States Census Bureau. https://www.census.gov/library/publications/2021/demo/p60-273.html

Turley, J. (2019, February 15). Elizabeth Warren’s popular plan to tax the rich is probably unconstitutional. The Washington Post. https://www.washingtonpost.com/outlook/elizabeth-warrens-popular-plan-to-tax-the-rich-is-probably-unconstitutional/2019/02/14/60195bc4-2fec-11e9-8ad3-9a5b113ecd3c_story.html

Walsh, B. (2019, November 5). The income tax, the gilded age, and what history tells us about a wealth tax. Barron’s. https://www.barrons.com/articles/ai-stocks-jpmorgan-banks-nvidia-big-tech-chips-3924f810

Zeballos-Roig, J. (2019, November 17). Here’s why Europe has mostly ditched wealth taxes over the last 25 years even as Elizabeth Warren and Bernie Sanders seek them for the US. Business Insider. https://www.businessinsider.com/what-happened-when-the-wealth-tax-was-implemented-in-europe-2019-10